主办:上海美术馆

中国民生银行

上海大家文化艺术基金

承办:上海艺博画廊

由上海美术馆、中国民生银行和上海大家文化艺术基金共同主办,由张晴策划的《方力钧》展览于2007年11月18日——2007年11月29日在上海美术馆举行。

方力钧,这位中国新艺术潮流最重要的代表人物,自中国后89新艺术潮流以来,与其它艺术家共同创造出一种独特的话语方式——玩世写实主义。其中的“光头泼皮”形象,已经成为一种经典的语言符号,标志着当代人一种叛逆、戏谑、躁动、迷惘的人文和心理。迄今为止,他的作品被收藏于法国蓬皮杜艺术中心、美国MOMA现代艺术博物馆、德国路德维希博物馆、荷兰STEDELIJK 博物馆以及上海美术馆等各大收藏机构等。

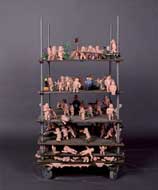

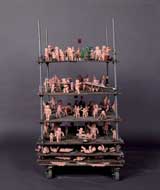

本次展览将展出艺术家近期创作的油画与雕塑近30件/套作品,其中绝大部分作品是第一次公开展出。在这些作品中,我们可以看到艺术家所呈现的一种更为放松的艺术状态,创作手法和思想意念都进入一种更为舒展的境地。其中的大型雕塑作品《生命》,悬空而挂,在长37.2米的刻度尺上,量化了人的生命,观众的心绪跟随着这些小人而起伏,表达了艺术家最真实的生活态度。艺术家借助自我的生活体验,通过更多样随机、更日常化的创作元素,以更为自由的方式呈现内心的理想和价值。

本次展览是继2000年上海双年展展出方力钧作品以后,上海美术馆首次举办方力钧个展,我们期待通过这次展览能使广大观众走近方力钧,了解方力钧,与这位艺术家展开一场真诚的对话与交流。

上海美术馆

2007年10月30日

Fantastic Realism

Text by Zhang Qing

The description of an artist’s creativity, often over-written in all kinds of art history books, is all about his or her art style or language. Yet when looking back about the pursuit of Fang ‘s Lijun in the past two decades, I suddenly realize that it is extremely difficult to judge an artist’s creativity in such an approach. Since an artist has different ponderings and artistic pursuit under different periods of time. For those who have luckily carved their names in the history, some keeps the same art style or even some just retains one “masterpiece” with minor changes or adjustments. Certainly there also exists some others who bravely and continuously experience the vicissitudes of the world and society and act in time with their new judgment and expression. Their artistic thought and practice echo with the unceasing transformation of the society, which reflect the inner creativity and energy of an artist.

In the 1980s, like other ambitious and experimental artists in China, Fang was influenced by the Western modern cultural thoughts. But at the same time, he reveals the nature of culture itself based on China’s reality and starts to conjure up his unique visual renderings. Fang and his art were gradually focused in the 1990s. His first phase is called “cynical realism,” a series of visual re-thinking towards his personal social status and social relationship in that period. Through unceasing adjusting and focusing, Fang uses an ironic way to describe the absurdity in his daily life. Those exaggerated and dramatic expression of himself, yawning or laughing images of the “small potatoes” actually ridicule the unbalanced ordinary life and social condition.

In a broad sense, these images are ridiculing what is happening in this world, the turbulent epoch that could never be quiet down. While in more details, he is recording the nomad living conditions and the unstable feelings of those artists staying in Yuanmingyuan at that time

Actually the natural trait in cynical realism is the ridicule of the unstableness of Fang himself. So the images under Fang’s brushstrokes are mostly self-mockery and ironic. They have double meanings: While they are laughing at you, they are laughing at themselves as well. It’s very difficult to use one word to describe its profundity and complicatedness, as wisdom is embodied in humor, self-confidence in self-mockery, and sharpness in irony.

The art that Fang created in the period has “multi flavors,” or to speak the earliest active “art of daily life.” But why it is named “cynical realism”? Realism has never been truly experienced in China, the word of “revolutionary” has cast a shadow on realism in culture history of China in the past century, and as a result brings out emerges “revolutionary realism.” Before realism starts to root in China, it immediately becomes “revolutionary realism” filled with a time spirit that could be used in politics and propaganda. Thus revolutionary realism went smoothly in the culture history of China. It is only in the 1990s that cynical realism was nurtured in China and revealed another extreme of realism. Based on a simple and sheer sociological angle, Fang together with his comrades vividly carves the expressions of our generation, the outlines our society through a humorous tone to link our heart with the obstacles in reality.

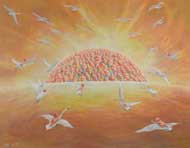

Fang displayed two colossal prints during the 2000 Shanghai Biennale, promoting the spirit and philosophy of cynical realism to a higher level. It is also an important twist and turn in his creations. The representative figures in his prints are simple and obvious, like one knows the purpose of an article by reading its title. Fang actually “borrows” the power of the grand revolutionary realism in these colossal prints. Thousands of heads are looking up, some are idiotic, some are numb and some are helpless, some are vague or some are expected. They gradually become hopeless in their hope or find their hope in the hopeless. The complicated psychological circle never ends. Fang acutely and powerfully points out the universalism in this living era. He expresses clearly an artist’s attitude and judgment of the society through these colossal prints. These heads looking up to the sky symbolize the collective feelings and plight of the ordinary group. This is an excellent milestone piece in Chinese contemporary art history. Fang uses his prints as a site where ordinary Chinese are entering into the 21th century, vividly carving the collective spirit through splash-like brushstrokes.

Fang’s next switch comes to the flying babies on his canvas. The baby bends over the cloud and looks down the earth. This is Fang’s beginning of symbolism, as the baby on the cloud symbolizes a free cultural soul. Fang shies away the external realistic world or the subjective cynical reality and creates a multi-angled pictures. In the picture, symbol is the main clue that guides any imagination towards the ethereal or the earthy world, ancient or present, East and West. These imaginations collide with each other and enter into an unknown area. Fang shies away of the natural trait in reality and truth, using an imaginative world to reflect the illusions of man towards reality and life. While at the same time, he develops such illusion, similar to the poetic feelings endowed by Li Bai and Du Fu, and leads the heart and soul of the viewers to enter into a symbolic area. Once the artist is able to bring the viewers to this “fairyland,” he is free to use any brushstroke. It’s hard to comment whether the scene is true or realistic. I think that Fang’s artworks during this period is akin to his life, as his fame and status rise steeply that enables himself to look down the seasonal changes of the earth in the angle of an angel. Thus Fang’s heart and eyesight are attached to this angel-like baby who cares about the society and the living world.

If the flying baby in Fang’s canvas represents the artist’s beginning of symbolism, then he truly comes to an unlimited fantastic and realistic world through his third switch. Here, the animals and human kind running day and night are grouped together. The animals whether of the past and present, of East and West all have symbolic meanings and rules. Flies, mosquitoes, cranes, golden fish, babies and angles in Fang’s canvas are pulling together towards the same direction. I couldn’t help myself rethinking of such a question: whether animal or human beings even divinities, whether sublime or contemptible, whether splendid or wicked, their flying and running direction is always the same. All those memories, good or bad that linger in the human’s mind are only produced on the world and applied to this world. In such prerequisite, if you think that a fly is evil, then the fly thinks the same thing back. In the sheer meaning of life, animal and human are the same, which is also true to the divinities in legend or religion. Whether human kind, animals or divinities, all of them have the same ideal and pursuit for a better living and future. Then is there any difference between a crane and a mosquito? Or an angel and a devil? In the Buddhistic angle, their lives are equal. Beautiful or ugly, good or bad, all are the polished terrestrial morality and ethics or even dreamy self-comfort. The change from cynical realism to symbolism and later fantastic realism forms Fang’s world view that evolves from forms to cognition, from attitude to thinking. The change also shows the brave experimental practice that Fang ponders towards life and art in the past two decades.

From this point of view, the animals and humans on his canvas happily leave the earth. He raises the human and animals: baby on the cloud, all the angels, flies, mosquitoes are dancing together. He symbolizes and metaphorizes all kinds of roles in the society via angels and animals. He puts them to perform together in the fantastic sphere. More vividly, the babies are riding excitingly on flies or bats, some even fall in faint or sleep on the cranes, and they welcome the resplendent sunshine and fly freely in the sky.

It’s so smart for the artist to put these roles under the same azure blue sky. Through his unique wisdom, the artist activates the power and energy of fantastic realism under Chinese cultural language. As if to echo with the fantastic reality, irony or descent irony always exists on canvas.

Theoretically, the soul, the attitude and the pursuit of the artist never alter. Fang only thoroughly remoulds himself in thoughts time after time, continuously engages himself in self-renovation and self-denying through artistic images. The academic meaning of this exhibition is to fully reflect the artist’s transformation from attitude to conition through fantastic realism.

History always chooses those creative artists while at the same time the creation of the artists also promotes and defends the completeness of the history. The artist’s transformation from attitude to cognition is not only the reality confronted by individual artist, but also a shared question facing those artists who have been active since 1990s. In the past two decades, China’s politics and economy change radically, so does the profound changes taken place in culture. What the artists focus today is how to face the selection and creativity of culture in a global sight, how to face the condition and relationship between all kinds of capital and art, how to face the special personal experience and the philosophy resulted in such experience. Thus what Fang has been exploring appears quite clear and vivid, profound and thought provoking. Undoubtedly, the artist’s shifts his interest in the basic characteristic of individual and natural trait of life in the whole universe based on which he reveals true and false, good and evil, beautiful and ugly on the earth with a poetic and practical spirit. All these are illustrated via angel, babies and all kinds insects in a harmonious surrounding. Human and divinity, human and animal, or animal and divinity share something in common. The basic trait of divinity, human and animal is historically unveiled and released in a chaotic and unlimited space on canvas. At the moment, you and me could stand in front of the fantastic world, and watch those divinity, human and animals struggling bravely towards a splendid great expectation.

- 《方力钧》个展研讨会文字实录个展研讨会文字实录

时间:2007年11月19日

地点:上海美术馆四层会议室

张晴:各位朋友早上好,方力钧艺术研讨会现在在上海美术馆正式开始。我先作一个简单的开场。

方力钧从九十年代以来一直是中国当代艺术最重要的艺术家之一,他的玩世现实主义的诞生形成了他突出的艺术符号,构成了我们这段历史的象征。

从这点上说方力钧个人的艺术思考、探索和这段的美术史是有直接关系的,在这个时段以后他有了自己新的形象——婴儿。

这个婴儿形象的出现区别于他玩世现实主义个人的、反叛的嘲讽和自嘲的形象出现,我觉得这是他这个阶段的思考和创新。这个婴儿的诞生是存在于我们的苍穹当中(我们的人类、社会、民生也好),但我想这个“婴儿”在方力钧心中是一个象征。

令大家欣喜的是在我们展厅当中呈现的又是另外一种形象,仙鹤、蚊子、苍蝇等各种摆设共同在苍穹当中飞向它们心中既定的目标,我想这是方力钧把“美与丑”、把各种问题看成是一个整体的态度,使得他的画面更加博大,使得他的艺术眼界越来越广阔。

从一、二、三阶段来讲我想是从不同层面展示着方力钧的艺术,此次上海美术馆能够把方力钧最近十年的作品汇聚一堂让大家来研究,让大家来思考我们这个时代,我想是一个蛮有意义的工作。

因此今天把各位汇聚一堂,希望大家从对方力钧的了解、研究和对中国美术的关系来阐述自己的观点。

我就暂时做这样的开场白,请各位畅所欲言。

李小山:我们翻阅任何一本关于当代艺术的杂志,以及关于当代艺术历史阐述的书籍都是重要的。

回想八、九十年代方力钧作为反叛的符号、作为一个另类,到今天已经成为艺术史重要的一章,见证了中国当代艺术发展的一个缩影。我相信在座的各位对他以前的作品都是很熟悉的,概括成“玩世现实主义”也好、“泼皮”也好我们都很熟悉。

这些新作我认为是方力钧的重大转型,对于岳敏君、张晓刚、王广义等等这一批我们平时开玩称作“四大天王”或是“四大金刚”的,这些重要艺术家的创作延续至今面临着一个对于他们个人来讲的转型问题。

如果不转型将会重复我们非常熟悉的那个图式,毕竟方力钧是我们视野当中紧盯的人物,他的转型说实在话至少我本人感到非常欣喜,这种转型预示着他的艺术道路已经开拓得比以前更宽广。对艺术家来讲语言是根本性的,没有自己的个人语言就会流于泛泛、价值是空的,很难落实到画面上。

方力钧成功地抓住了他这个新的转型期这样一个新的语言表达,我感到非常欣喜。

另外他在题材上大大地拓宽,不仅是在描绘的对象上,甚至在意义上有宗教感。以前对人物、对象是社会感,现在把对象性扩大成“人与宇宙”的关系。人在宇宙当中的关系本身不管是婴儿、苍蝇、各种各样的动物,甚至带有一些装神意味的各种意象,都使得方力钧的艺术道路大大拓宽。

这种拓宽对艺术家是非常重要的,早期的成功让我们认识了方力钧对中国当代艺术史的价值,由于这批艺术家的崛起使得我们的当代艺术史有了初步的价值。

从苏联到后来改革开放以后全盘西化,到了方力钧这群崛起,从吕澎解构当代艺术史里面大量的材料见证了这个过程。到了今天终于我们看到了方力钧作为一个艺术家这种创造力的延续,这种创造力就是艺术家的生命力。我们回顾中国文艺界,包括电影导演、文学创作、诗歌,艺术家最大的弊端就是创造力的枯竭,在某个阶段爆发一下迅速枯竭。

这里面的原因我也一直在考虑,老一辈艺术家在某一种方式确定以后不断地重复,画过一、两张代表作之后创造力中断,这样就形成了尖锐的反差。所以在这代艺术家身上,我们看到了非常欣喜的表现,创造力还在延续。创造力的延续预示着中国当代艺术会走向更高的台阶,这就是我看《方力钧》展览以后非常鲜明的印象。

谢谢!

吕澎:短短的时间讲不了太多的问题。我倒是想交流一下一些问题,同时也有一些建议。

最近几年尤其是在完成了2000年的《当代艺术史》之后慢慢养成一个习惯,我们都知道八十年代是一个阐释意义的年代,作为艺术批评来说在艺术的意义上做了很多文章。

但是,从七九年以后到现在将近三十年,关于现代艺术也好、当代艺术也好有很多讨论、分歧和意见,尤其是在和我们一般意义理解的传统艺术、官方艺术或者是缺乏创新的艺术和当代艺术之间,总是有很多没完没了的分歧,只是说在九十年代以后认认真真的讨论少了一些,没有像八十年代那样认真地讨论问题。

我想说的是在研究过去艺术价值和意义的时候,我们用很多笔墨和时间去关注作品的意义,去阐释作品本身形而上学称之为艺术本体层面上的东西。但是2000年以后我是在思考为什么还是有大量的艺术家、批评家当然包括观众对当代艺术仍然不懂,昨天在跟一个艺术的投资机构负责人讨论这个问题,他说你说谁好就谁好没问题,但是我还想一个问题为什么他们好。我看着这些作品实在是看不懂那些东西,当然我现在听你的,但是我们还是不知道好在哪里。

这要提出一个什么问题呢?我们不能够停留在形而上学的浮想联翩上面。我们不能用各种词汇不断地去搅和,经过几十年大家都很清楚,任何一个词汇、概念缺乏一个基本的语境这个概念就没有意义。一个最通俗的概念,我们可能大家都很明白。

其实如果我们没有放在共同确定的语境,今天的讨论就没有意义,所以为什么有时候在讨论问题的时候我们没有办法去寻求一种共识,其中的一个原因就是我们谈的基本语境是不一样的,我们的出发点是不一样的。

所以在这样的情况下我们要了解一种艺术现象,就不可能是仅仅从所谓的思想、哲学的层面去剖析很深刻本质的含义。我们知道深刻、本质这些概念都要慎重考虑。

所以我就越来越习惯于看待一个现象应该去找到产生这个现象最基本的原因,找到非常客观的、不可避免的历史和现实当中的上下文。当然也要关注艺术家的DNA排序。

我想这就回到方力钧的艺术究竟在当代艺术里面处在什么样的位置,能起到什么样的作用,就像昨天开幕式上说到推动当代艺术的发展,怎么推动,凭什么是推动?显然我们都知道肯定不是从展览的规模、作品的大小、作品的数量,肯定里面有一个东西,怎么来寻找这样的东西,我是越来越习惯于从艺术现象很具体原因的上下文、从艺术家自己的一些特殊经历去了解。

所以从这个意义上讲对方力钧的转型,我们当然可以按照我们的知识背景,按照我们对当代艺术的了解做一些阐释,我更愿意找到一个具体的时间跟艺术家本人做很细致的沟通。在沟通过程当中我们起码看到艺术家本身真实的出发点,找到有些最基本的原因,回头再来作出判断。所以我现在越来越有这样的习惯,不太愿意、也不太敢轻易地对一种新的艺术现象,新的转型,新的风格去作出判断,所以这是一个问题。

我要谈的就是我对一些事情基本的看法,当然毫无疑问你看了展览总会有感受,会有反应,不能说进去没有看到东西,所以还是有一些很基本的反映。

我有这么几个比较基本的反映,这些反映不足以代表我对方力钧最近作品很成熟的或者是很充分的认识。

第一个是九十年代初的作品跟我们今天所看到的作品进行比较,我觉得在我的感受中九十年代初的作品或者说九十年代上半部分的作品或者延续了很长一段时间的作品,更多的是一种态度,是一个态度非常直接的一种生活经验,一种态度非常直接的一种表达。

可是在展览里面所看到的新的作品反映说它不是一个态度,它是一个态度之后的究竟有三圈、四圈不断循环思考之后的思想,我对问题有一个判断,可是艺术家说我对某种议题有表达,可是现在其实我有自己的看法,这个看法和简单的表达不一样。

我觉得按照我们一般的生活经验,从这些生物(苍蝇、蚊虫)符号中我们是可以得到很多判断的。所以,我想从态度的表达到思想的表达,我想这种转变可能是比较重要的转变。我们有很多人说当代艺术究竟是什么?我们在过去的讨论会上经常会讨论什么是当代艺术,我们在具体面对艺术现象、艺术作品的时候,可以找到这个作品中间实际的最具体的问题来抽出一个当代艺术的例子,来真正表达我们对当代艺术的看法。

所以我想这种转变是非常有意义的,我们真正要说推动,什么在推动?显然不是规模、人流在推动,是里面真的所要表达的东西有可能对当代艺术的影响,究竟说了什么,说的东西和过去是什么样的关系。它和今天的其他艺术家说的关系是什么,这种关联性是我们了解今天的当代艺术最最重要的部分。

第二个就是显然可能看到因为综合的材料的使用,起码能够表达除了一种态度以外,要表达一种思想需要通过更加丰富的手段,所以第二个就是很明显采取了更丰富的手段。

那么为什么要用这种手段,为什么这样来表达?这些实物被称之为装置、雕塑,它们和绘画之间是什么关系,跟以前比较(尽管在上一次今日美术馆已经有一些表述),这次展览的充沛性和他所表达的具体内容有更明显的区别。

所以也跟我刚才所说的不是简单的态度问题一样,他希望通过尽可能丰富的手段去表达他的思想,而这个思想不是我们一般意义的美学阐释,这个用一般意义所谓的哲学来阐释可能会形成一种浮想联翩的结果。

第三个体会和前面两个有关联,如果我们能够找到这个转型和新的艺术表达的这样一些原因,他所要表达的东西正是我们今天所具有针对性的,当代艺术的合法性才能够得到进一步的证明,所以我们现在来证明一直在讨论当代艺术,大家都希望来讨论当代艺术,所以每一个人都是一个当代艺术家,最后八五都变成当代,有一些批评家、理论家、学者为当代做一些概论性规定,我觉得这样很劳累。

事实上,要按照时间的表达,我不知道是什么原因(可能当代太时髦),把八十年代也说成当代这是没必要的,因为一个词就是一个历史语境当中的词汇而已,不要乱用,所以八十年代我们说是现代艺术、前卫艺术其实很准确,那个时候有那个时候的概念。

这些新的艺术、概念里面提出来的什么东西使我们的当代艺术具有合法性,如果把这个问题说清楚其实我们讨论什么是当代或者相对比较容易。

我们来检查一下什么样的艺术现象能够成为我们这个时期,我们这段历史相对具有代表性的艺术现象。这样我们对一个历史才有清晰的看待。

我想方力钧的展览我要说的就是这些,我觉得在原来的作品里面更多看到的是态度,现在的作品有他的思想,并不是我对他的真正想法很清楚,我真的是希望和他去沟通。我认为这种复杂性是存在的。第二综合的材料本身证明了他要表达他自己的东西,其实是希望把话说得更清楚,而不是一个符号出来马上就能说清楚的。我记得最早在圆明园的时候,有一天去方力钧住的地方,他在地上的画靠在墙边,我那天一看到就知道是什么,我马上知道是什么态度,我要坦率地说我们今天看到这些作品,我不能去浮想联翩,我们当然可以从哲学、思想去做很多的阐释,但是我想最慎重的方式仍然是要去了解艺术家,了解艺术家做这批作品的真正出发点。

我们当然很有权力,任何人有自己的想法可以去阐释,但是这个权力不能滥用。所以我认为按照我个人的经验,如果说我们在书写历史的过程当中还有很多缺陷,我认为最大的缺陷是对艺术家的了解更欠缺。

我们毕竟缺少的不是理论、概念,其实还是缺少深入的、认真的、直接的和艺术家进行沟通,这是我们今天最缺乏的,我们很多展览每年365天的展览都可以排下来,可是有哪些展览、哪些艺术家是值得我们认真对待的,所以我最后的建议是以后的任何活动(批评会议、研讨会议)最好类似于真正意义的法庭辩论会,我们真正是在找问题,我们是针对一个艺术家的行为去发现他之所以有这样行为的各种各样很具体的讨论。通过这些数据的了解我们才可以对艺术本身、艺术意义作出很好的判断。

汪民安:刚才吕澎先生讲得挺好,我有一点不太同意。关于对于艺术作品的解释一定要了解艺术家,要对艺术家的情况特别清楚、沟通,我个人觉得真正的艺术品的魅力、意义,而且从历史上来分析,所有伟大的作品之所以伟大就在于可以引起各种各样的反复阐释,而《红楼梦》我们为什么有那么多的解释,是因为有各种各样的解释和《红楼梦》的意义在不断地解释过程当中才阐释出来的。

人类的文明就是人类的解释史,如果我们把一个艺术家的意图,自己的想法或者计划作为艺术的终极意义,这实际上是对它的扼杀。

从我个人角度来说任何一个作品某种意义是一个世界融合,你或者别人、艺术家本身有一个视野融合,在这个理解的过程当中才获得这个意义的,而不是这个作品的意义就存在着艺术家的心目当中,这是我的一个前提。

再一个接着李小山先生说的,他有一个说法我特别同意。艺术家到了一定的年龄、岁数之后创造力枯竭,这恰恰是中国特别明显的现象。

八十年代中国有各种各样的小说、电影也好、文学、诗歌包括艺术,八十年代出现了非常好的东西,那个时候出现的东西有时候是不可想象的,那个时候历史资源不多,但是创造力非常旺盛,现在来看是不可思议的高度,当然为什么很好的一些导演、小说家到了五十岁的时候就马上不行了,这是中国特别的现象。张艺谋、陈凯歌都非常有才华,到五十岁都不行了,我发现很特别的现象,国外的导演、艺术家七八十岁还是继续有那样的高水准创作。

我和很多人讨论为什么中国没有非常好的老艺术家,我们只有好的年轻艺术家,年轻的时候大家都有很好的创造力,我一直想中国存在着中年艺术家创作危机。

姜文现在拍这部片子(《太阳照常升起》)不如当年《阳光灿烂的日子》,从这个方面来说方力钧现在差不多到了中年了,我不知道他有没有中年危机,从目前来看方力钧在努力克服这个事情,在克服到了中年的时候开始衰退,中年的时候身体衰退就是创造力衰退。

一个人最重要的不是说有什么好作品,而是一直能保持创造力。

所以我特别地希望方力钧不是说在做了某一件作品,可以保持一辈子还是一个好的艺术家。作品不重要,创造力重要,我觉得这是说的第二点。

我还要说一点关于方力钧的作品,方力钧的作品(原来在八十年代以前的作品)刚才吕澎说了比较好理解,就是有一些比较明显的意识符号,有一些历史的东西、阶级的东西,对抗的东西,可以说里面充满了不屑,暴力对时代抗议的表达,这些东西在方力钧的作品当中都成立,而且确实是非常好理解。他今天的作品到现在这个时候给人的阐释确实带来了困难,我们看方力钧的作品到底看到了什么,想说明什么,吕澎先生说了也不好一下子明白方力钧到底要说什么。

从我个人角度来说我不管方力钧到底要说什么,而是这个作品对我来说意味着什么。

我觉得这个作品和生命有关系,为什么这么说?因为方力钧最近这两、三年的作品,我们自己感觉印象特别深的婴儿,运用了很多刚出生的孩童。

我们说方力钧的作品和生命有关系,如果我们从生命的角度来讨论这个事情,我们不要把生命局限于人,生命同时包括人和动物,方力钧这些作品当中人和动物的关系我觉得非常重要。

人和动物的关系,实际上就是我们的人目前要谈人是什么动物,人是和动物不同的,人根除了自己身上的兽性,这个时候人才变成了人。在方力钧这里恰恰是结合在一起,人有一个动物的头,这恰恰是人和动物的一个结合,在这里我觉得很明显,另外人和动物在方力钧这里有自身的阐释。人身上可能有的动物性是一直存在的,人身上既有动物性、有人性,还有神性,人同时存在着三种东西。

我觉得方力钧特别地强调人身上的人性和动物性的结合,这种结合可能就带来两种效应,一种效应人和动物一样都是微不足道的东西,都随时可以被这个社会、历史、大千世界扑灭,人就是和动物一样。

我们可以从积极方面来说,人身上还有自由,人所谓的文化、文明我们所说的人性的东西建立都是通过人类把动物进行驯化,我们所说的人本身都是野兽,都是动物进行驯化之后,人类文明就建立起来了,同时人类之中有反驯化的东西。人一方面有卑微感,方力钧的作品当中有大量飘拂飞翔的东西,方力钧有对自由的向往,什么时候才可以更自由,什么时候是虫子的时候才变成自由。方力钧很有名的画讲什么时候能够自由,就是发疯的时候可以自由,人成为动物的时候就可以自由。

人可以被任何东西给捏碎,人的动物性一方面既可以带来自由,另一方面可以变成牢笼。

这是我自己对方力钧近作的一些理解。

张子康:我是站在一个观众的角度去说。第一次做方力钧的展览,给我一个特别深的感受,尤其是观众对展览的感受(多层面的观众),我觉得从一个老百姓的审美角度来说,实际上他在历史上起了非常重要的作用。因为他在原来的审美体系上有了新的发展,实际上在那当中往往是感叹审美,推进的审美往往是在历史上创作了大师。

当时老百姓看了这个作品的时候觉得看不懂,他这样的作品怎么可以挂在家里?大家往往碰到这样的问题,这样的东西好看吗?怎么这样的东西可以挂在家里?

后来我就发现人们包括收藏家不断地从书上看他的作品,讲述他的故事,画的什么东西,再看美术史逐渐地改变了这些人的审美。

我觉得方力钧的作品在历史上把整个中国的审美往前推了一步,我觉得这个从美术史上有特别重要的意义。

这次的作品展出在讲生命的故事,好多作品我们看到以后很振动,表现主题非常强烈。

胡永芬:在座的大部分人都比我有更长的时间、更多的机会去跟方力钧接触,了解他的艺术,了解他的生活,所以我只能从瞻望的角度来做一点感想。

美术史如果作为一条长河可能会受到很多偶然性的影响,山形、地貌、不同的气候等等,所以可能在整个的发展过程当中有很多偶然的因素会改变它的方向,我的感觉方力钧在整个美术史这样一个长河里面就是这样一个偶然的因素。一个对于整个河流的方向或者是它发展的轨道有关键改变的角色。

其实从我的角度来讲艺术是很轻松、很容易、很幸福的事情,只要做了艺术家本身就是很单纯的事情。但是从另外一个角度来看也是一个非常艰难、残酷的事情,它对于当下集体的生存状态怎么样能够做到一个关键的代言,以及对于未来的艺术产生关键的影响,我觉得这对于大部分的艺术家来讲,或者是说对于有企图心的艺术家来讲,这都是一生来追求的目标。

我的感觉是方力钧做到了这一点。

我就简单说这些。

冷林:我和方力钧接触时间比较长,从九十年代一直到今天变化还是很大的,当然这个变化我觉得也不仅反映在艺术家个人身上,整个的社会机制、体制在我们身上都令人瞠目结舌。

九十年代,大家谈到绘画,我个人理解方力钧很清楚的知道把自己有意识地放在一个环境里面,当时看到好多绘画也是画了很多从周围的环境当中受到鼓舞来展现的嘲讽、愤怒。

更多相比较而言是中国艺术当中的另外一个方向,这个方向我觉得有的时候比较难理解,现在在整个国际舞台上面我觉得就是一种生命力,实际上就是展现的像杂草一样到哪都可以生活,是一种生存力,我觉得就是一种烘起来的巨大生命力,我觉得这是另外一个方向。

方力钧还是有原创力的,好多东西是没有来源的。那些图式没有来源,画得都很任意,这种任意当然有的时候更多地是传统的修炼,又不控制数量,也是很自我的东西没有环境了,不像九十年代还有一个对象。

今天的绘画我觉得没有对象很自我,就是一种生命力,当然最主要的就是控制,有些东西控制在什么地方,展现出来中国绘画的是另外一种方向。这种方向也是在全球当中展现出来的生命力,这种生命力放到更大的背景下面当然是从中国现在高速发展下突然出来的,按照地域来讲都不是人的概念,但是又突然出现在现在这个世界上。

所以这个艺术我觉得还是可以从重要层面去了解,从更广阔的重要的层面去理解。这个艺术对现在来说是一种所谓的主流艺术受到很好教育的一种主流艺术和知识分子主流艺术一个新的填空。

这是我的理解。

冀少峰:我看方力钧的展览感受很深,上次在今日美术馆也看了。其实老方进入艺术领域是玩世现实主义一个代表。

老方最大的贡献就是艺术的颠覆性,对于艺术在图像上来理解、在颠覆性上的变化。

最近这些作品和这个非常有关系,当年中央美院很多导师都去体验生活,很多作品反映了本土的东西。 另一方面在这个变化当中仍然起到了旺盛的创作激情作用,画面体现了非常丰富的东西。这是对艺术家最高的评价能够获得一种激情,能够对生命自由精神。

他曾经有一个名言:像疯狗一样去觅食,对中国文化进行侵略的时候,老方的作品当中体现了这种追求。

更重要的是旺盛的创作激情和自由的意识应该对我们今天的这种商业化有一个促进作用。

杨卫:方力钧是我所知道的最持续关注人的艺术家,生命是如此持续坚持地关注。

在他之后我想有一个词可以使用,从他那个地方反过来应该叫身体的恢复。

在这之前我们知道八十年代的中国当代艺术很多实际上都是很概念化的东西,也就是说并没有尝试也没有体验,仅仅是从书本上或者从一些概念挪过来,这些东西我跟方力钧这样一个身份的关系。我们知道方力钧是属于最早的一批盲流艺术家,这样的一个背景肯定跟我们所说的知识精英的背景不一样。

他更加注重于体验这么一个状态,所以他的艺术关注的是和生命有关系的,而且这种生命非常自觉地、非常感受性的,他还有一个很重要的特征。他的作品非常有感受,但是他的处理方式又是非常理性的,这又让我想到了哲学上的一种概念,像尼采这些人,感受性的,但是实际上是以感受回到一个理性的空子这样的一个感觉。

具体说到人的问题,具体到他的作品我觉得有几个元素过去很少有的,比方说是一个云彩,还有一个水这是他常用的符号(除了人以外)。

这几个符号没有具体的意义,很抽象,正是因为有这样的符号才把一个人的背景读出来。我们知道云是很抽象的东西,包括水没有具体的所指。所以方力钧的艺术我们从长远来看实际上从画面来说是没有社会背景的,仅仅是关注到人的生存状态,至于这个人可以放到秦朝、明朝,甚至可以放到未来,这是他的一个特征。

而且这个特征反正我所知道的至少在新潮美术之后很少有的一个特点,可能我们对中国的古代反而有这样的元素,知道水墨画、山水画里面对人物的感觉是很抽象的。

所以从某种意义上也是新文化运动以来包括鲁迅这一批人以来始终提出人的问题,但是落实到作品本身很多是概念化的。身体力行地通过身体的感知去感知生命这样的状态应该说方力钧是首当其冲的艺术家。所以他处理的方式有很多借鉴,包括我最早认为他有一个方式,比方说用的我们过去所不屑的语言方式,像年画一样,过去是被精英文化扬弃的东西,他拣过来。包括金鱼这样的符号都民间化,像民间的挂历,尤其是那种农村的挂历,这种东西是被精英社会所不屑的。恰恰在他这个地方拣过来复活了,他紧紧扣着人生的东西。

说到他现在作品的转型,小孩童的符号,这次始终是和生命有关系,人到中间是有的。我想每个人都要经历过这样的东西,也就是说他到一定的年龄段以后要么就下降,要么就升华,必然要作出选择。有一种人生的情绪是在变化的,不可能人生永远是一种情绪贯彻到始终,我们认识情绪或者说去感知生命这样的情绪是持之以恒的。

所以接下来我开始接着前面所说的,我也特别赞同以划代、以新生代为艺术的理由,这个问题可能跟中国整个社会有关系,我们现在是一个求新、求变的社会背景,逼的人们眼睛始终去盯着年轻的,年轻的始终是好的。

这样就好象我们的文化始终停留在表层,我想更持续的关注,就像方力钧关注人生的问题一样,我们批评家应该持续地去关注,尤其是中年这批艺术家他们的转型。只有这样的东西才能把我们时代的感受或者文化感知带入到一种深度思考的层面上,历史翻过一页以后才能真正留下一些东西。

吴鸿:我觉得从九十年代初方力钧当时一批艺术家作品来看,方力钧是在每一个历史发展的阶段都能够去比较敏感或者说比较准确地把握社会心理的这么一个艺术家。

我觉得八十年代历史形态发展到九十年代,我们现在回过头来看八十年代应该是比较理想化的社会形态,到了九十年代因为经济的发展变化,带来了人的心理上的落差。

我想老栗应该是比较准确的分析,当时有一部电影《过年》就反应了这个家庭里面几个家庭成员社会角色的改变,正好就是当时社会的几种心态的象征。它有一个家庭成员是中学老师,从八十年代以来这种理想化的状态,还有一个人是当时做生意的,就相当于所谓今天刚刚有自由经济这样的状况。还有一个人是下岗工人,通过一个家庭里面很小的矛盾把社会和态度纠缠在一起,它很符合九十年代初中国社会这么一种状况。

方力钧当时还是基于知识分子这么一个立场,我们从八十年代以来理想主义精神的失落,它带来了人的空虚感和精神没有着落的状况,九十年代中期到两千年以后随着中国经济的发展,中国的社会形态也带来了无限的可能性。中国人的生活状态也带来了无限的可能性,在上海或者北京,从整个城市的形态,建筑样式是非常丰富的景观,相应中国人的精神状况也是非常多的可能性的状况。

我觉得方力钧2000年以后的作品,是更加对于深刻的人性的把握,所以我昨天在最大的那幅画里面看了以后有种感觉,有点像刚刚说的审判的感觉。

另外从语言的角度来看,作品所表现的对象和他表现的题材,早期他的作品纯粹的版画语言里面反映他的作品比较概括理念的风格,近几年实际上他尤其从民间年画包括作品的装饰性,我觉得有一点他早期的作品比较概括,现在的作品比较烦琐。

我觉得中国社会的心理状况也是有一定的对应关系,另外我觉得这个展览对于方力钧来说可能不仅仅是一个主题性的、回顾性的东西。

刚才小山说到和方力钧同时期的艺术家面临着同样一个问题,其实艺术家这样的变化是很自然的过程。对于他们来说他们在某一个阶段的作品取得了最大的成功也是有很多影响,以方力钧的作品来说现在很多人模仿他。对于他们来说特别是艺术市场的介入,又是给他们这些人个人语言风格的发展带来了巨大的心理压力。

我觉得对于某一个艺术家来说,就相当于我们前一代艺术家取得成功以后会对下一代艺术家带来无形的压力。

对于他们来说某一个人不同的阶段相当于两代人之间成功的压力,所以这种状况似乎对他们风格转型来说看起来似乎有一种悲壮感。

从方力钧的个展来看他为人处事都是一个很有控制力的人,他实际上把这种风格的转型也控制得非常好。这个展览对于方力钧的艺术发展预示着很多的可能性。

邓平祥:我想谈三点。

第一,我觉得方力钧在八五年产生不了这种艺术,一定要放到八九以后,当时的社会情绪,政治的、社会的、心理的,尤其是心理的层面,如果放在这个里面去看就找不到合理性,也找不到深层的原因。

他最后选择了泼皮和玩世的现象就是面对中国在精神领域中间群体的失语,尤其是正面的方式不行,他就自然的找到了泼皮方式,这种方式刚才我很认同杨卫先生所说的,就是与他的个体背景差不多,他不是一个真正意义上的知识分子,他又是从大学受过高等教育出来,又是在体制以外,又是在圆明园打散了以后到宋庄,这种经历实现了愤怒、无赖、反抗、自嘲。

这种意义在于解构和批判,但是方力钧有一个非常重要的特征我认为要特别提出来,他把自己放进去。

这个很重要,很多画家就是居高临下看别人,不把自己放进去,方力钧是把自己放进去,他那种独特的图式符号就是把自己放进去了。

这一点我认为是特别值得提出来的一点。

我觉得方力钧主要的艺术深层的方式加上感性生成了他的艺术,他用的情绪和感性是文化转型中间的或者一个大的事件当中转折性的认识和感觉,和一般的区别于野性的存在,只有用野性民间的方式才可以反抗体制文化巨大的压力和巨大的存在。

那么因为这个时候我们中国还是国家主义美学占上风,方力钧这种方式是以他个人的方式比较彻底地颠覆了国家主义美学的一种表达方式和一种艺术方式,我认为这也是非常重要的。

但是,有一点我想提出来的就是这种野性和这种体制性只有一步之差,比如说文学当中的王朔就是彻头彻尾的痞子性。这个就是对文化在前期可能有某种反抗意义,但是马上破坏性远远大于反抗性,所以王朔的艺术挣扎了好几次也没有出来,就是他无法承担反抗,不负责任的反抗。

他们之间还是有区别的,这就是方力钧的艺术为什么比较有一些生命力,这和王朔的区别在这儿。

中国的精神文化层次里面由于多年的政治斗争,造成人的精神紧张错觉,我们这种年龄的人特别有感受。中国人是非常有紧张感的,碰到一个问题马上就紧张,没有一个文化上和精神上的缓蚀剂,面对紧张的东西没有认识的东西那种程式性的精神功夫。

这个时候产生方力钧的玩世、泼皮这是一种有积极意义的,还有提示另外一种方式,我们不要太紧张,我们对于一种强大的、无比的、体制的东西其实可以以另外一种方式来对待,这种方式对待实际上至少我解脱了也提示人家采取另外一种方式,这个我认为也是一种弱势的生命个体某种意义上的精神指挥。

我觉得这点是非常重要。

第二,方力钧艺术的来源。

刚才冷林先生说他的来源不容易找到,在某种意义上我同意这种说法。

因为人类学家说过一个时代的人和文化总是三种引导的力量:一、英雄的引导力量;二、传统的引导力量;三、他者的引导力量。

我们分析一下方力钧的艺术在三种引导力量中间来自于哪一种领导力量呢?

英雄的领导我看显然是没有的,他的东西绝对不受英雄层面引导的东西,传统的引导也没有。但是他者的引导里面可以找到一般的意义,他这种形式层面艺术层面还是有西方艺术一些启示性的东西,但是他的精神引导我认为不是西方的,他是自己的引导,自我的引导,他是源自内心的情绪和感觉。

所以他的艺术表现了非常突出的个人性,在当代艺术中间无可替代,我们也找不到。

并且他力度特别大、很酷,这种酷就表现在力度特别大,力度是他超越了所有的现当代艺术家。

第三,我想讲转型。

我们这个展览看了以后我也想了,我也和一些批评家交换了意见,他的这次转型和变化给我们通常的解读带来了困难。

这次转型是图式的、语言的、精神的、材料的、综合性的推进,所以就给这种解读带来一种困难,尤其我注意到他这种图式中一个重要的图式,比如说开幕式后面大的招贴画就是一个天使。

大家知道这种现代艺术的展开尤其是现代性的展开,现在很多哲学家说是把魔鬼和天使一起放了出来,方力钧的艺术中间出现了天使的图式。

我至少一半认同刚才有的批评家说的,这次转型是初步的有一种情绪和感觉、感性,往某种思想性的层面转换,这种天使符号的出现是商业性的东西,绝对是建构性的东西。这一点当然我也没和方力钧本人交流过,这种符号我认为还是某种意义上足以代表艺术家的东西,因为艺术家的生命就是他的作品。

过多的个人阐释或者个人的解释其实在某些时候是没有必要的,我一直认为我们从现代艺术进入到反思,我本人从八五以后写了很多文章,都是现代性和现代艺术建构的。但是近几年来我重复地卷入了对现代艺术更深层的思考,思考就引入了一种带有批判性的东西,我们的现代艺术中间把天使和魔鬼一起放出来,魔鬼对我们的现代艺术意味着什么,尤其是对我们中国这种特殊的文化意味着什么。

现代艺术就是非审美化的,审美对于西方的精神文化是有非常大的合理性关系的,对于中国的文化意味着什么?因为中国的文化到了明清以后,我们的审美文化已经整体性地被解构掉了,而西方的现代艺术又是非审美化的,这和中国的文化环境就是一个矛盾。

我们怎么解决这个问题,当然我还和一些人交流过,我们中国碰到了、遭遇到了后现代,这种后现代是对现代艺术一种重新的反思,包括对古典这种审美艺术的一种重新认知。如果从这个意义上说我认为方力钧的艺术真是带有某种现代性。

所以我就感觉方力钧这次转型是不是意味着他一种精神层面的文化反思和文化自觉,我的感觉自己是一个开端,我就说这些。

邹跃进:首先我还是对吕澎和汪民安的发言谈一点看法。

两个人一个代表社会学的艺术史,一个代表人文学科的艺术史,我觉得这两个都要。

社会学的艺术史很重要,另外一个人文学科的阐述学也是非常重要的。所以我在人文学科上同意汪民安的看法,艺术的魅力确实在于可以无穷地解释它。

第二,对方力钧的艺术我有一个基本的结论,他是“八五思潮”或者说八十年代启蒙知识分子对中国的批判在九十年代的一个结果,这是我一个基本的判断。

这个我曾经进行过阐释,还包括张晓刚这些人,启蒙知识分子对中国的那种彻底否定,总算有了一个新的结果。这个新的结果是很有意思的。

这是他九十年代到这批作品之前的一个我的基本判断。

我想谈一下我对这批作品的看法。

我基本同意上面一些朋友们的判断,确实在转型,我觉得那个转型有两个方面。

第一个方面,转型中间延续了很重要的过去的东西——中国特色。

另一个方面,超越的东西。超越的东西最重要的就是婴儿和动物这个形象的意义问题,我们又要发挥批评家的权力了,这个权力不管是吕澎给不给,我还是要发挥一下。

在中国最早的哲学思想中间,老子就提出要福贵婴儿。万物其一对于人来讲最好的状态就是婴儿状态,所以在我看来刚才汪民安从三个角度(人性、兽性和神性)来谈了。

但是我想就我的感受和阐释来讲,我觉得是万物其一的看法。

不管是人那么真正的回到婴儿状态才是重要的,给了一个翅膀是很好的解释,这个翅膀恰恰是所谓的老庄哲学中间福贵婴儿人所获得的无知无欲的状态。

在我看来当然有另外一种东西,有一种当代性的解释,所谓当代性的解释是图像包括语言、呈现的方式,这是一种当代性的解释。

但是我觉得这个里面可以和老子的福贵婴儿有一种辉映。

我想在这个基础上面我们还可以更多地来理解方力钧的作品,当然这个我也没有和方力钧交流。

我想在此基础上还可以讨论这个意义。

鲁虹:我想到汪民安在隋建国会议上面的发言,他说现代艺术市场上的力量就是靠资本的博弈和一个艺术家获得一种身份,有了影响力就有了一切。

他那个讲话确实是很有道理的,但是我觉得还有些偏激,我不太同意。

我想刚才很多朋友们谈的问题,也提出了这个方面的问题。

我觉得从风格的类型上看方力钧的画属于具象的,但我想是用一种超现实的组合方式,形成了虚构的表达结构。

由此象征性地表达了对中国消费婴儿的一种生存状态的关注,我觉得看他现在的画跟他以前的画一样,思维方式是中国化的、本土化的,因为他早期的绘画还是受中国的痞子文化影响。

他自己转换形成了独特的思维结构,这对他的画面结构是非常重要的。

他把个人体现出的符号包括传统文化里面的符号组合起来形成一种超现实的表达,刚才冷林讲方力钧的画没有来源。我的理解是指没有艺术史的来源,更多的是来自现实日常生活的感受,方力钧和好多人谈话都谈到了日常生活对他的影响。方力钧从日常生活切入,他的画这一点不是像一些当代艺术家从西方的画册里面转化的思想和图式。

他是从自己的现实生活当中找到感受,把这种感受转换成符号。和今年的油画作品相比方力钧的绘画明显对传统绘画是有偏离的。我们看待一个画家就看他在拒绝什么,他在吸收很多东西。

比如说他在色彩的处理上,虽然受了西方色彩的影响,但是和他自己谈话一样,他基本上是在中国的概念里面合理借鉴西方的概念来表达的,基本是散点的,不是西方的焦点图式。

在具体的造型上包括塑造上面,我们看方力钧的画来源肯定不是从西方的油画史走过来的。大家已经谈到了从传统的年画包括甚至水墨画获取一些营养进行表达,这不是一个形式问题,这和思维结构和中国画的结构是吻合的。

我觉得整个中国化、本土化、日常化是他一直贯穿的。

婴儿和消费文化的关系,婴儿和价值感的关系,汪民安说的无限的解释留下了很大的空间,所以他的作品我们每个人都可以带着自己的理解来解释。

刚才杨卫说他的画就是在消费背景下产生的,他把消费文化婴儿一代深层的面临的一种处境解释的非常清楚。

总而言之,我觉得确实我看到方力钧画之后一种创作的能量,因为以前一直看到他反叛的“光头”。我们也看到他新的转化,这是非常了不起的。借这个机会表示祝贺,谢谢大家。

吴鸿:我觉得方力钧作品当中的婴儿形象,不能简单地把这个符号这种价值指向简单化。

婴儿形象仅仅是艺术一种新的符号,而且这和他个人的生活经历有关系,大家都知道方力钧中年得子也是一个非常高兴的事。第二我觉得他精神里面是一个复杂性的东西。

不管从绘画、雕塑也好,就算是天使也是带有魔鬼性的天使,还有铁笼子里面装小孩,很像我们小时候一些生活经历,所以我觉得他的这种形象不是一个简单的对应关系。

邹跃进:我想艺术的体制化可能是艺术家的宿命,两种体制化:一种是社会主义体制化,一种是资本主义体制化。

咱们是没有本事逃脱,我觉得这是体制化的结果,艺术家可能也在这个悖论之中,我们都在这个悖论之中我们要认可这个现实,所以在这个意义上来讲我觉得要看到它的复杂性。

俞可:汪民安的发言非常有意思,至少给我们提供了一个新的思路,我个人认为影响中国当代艺术的不是什么思想,也不是什么艺术批评,也不是什么媒体。

这些东西都被大家夸大了,我觉得影响中国当代艺术的是资本。

在资本的作用力下中国当代艺术有了一个火红的场景,在这个场景下艺术家如何保持自己的艺术自觉非常重要。

从上个世纪九十年代我们中国的前卫艺术搭上了国际列车,当代艺术一直面临一个问题。因为当时就是在那种意识形态样式的照相写实主义和批判写实主义这种模式是不是能够继续沿用下去,究竟有多大的突破,我们把这些老一代的艺术实验做一个综合的对比是显而易见的。

今天我们应该做什么样的事情,我想方力钧在自己的一个时期和一个阶段的个人创作里面有显现。

但是这个显现是不是有成效,真正是代表今天的艺术,我觉得确实还是值得实践和探讨的。

因为风格、样式还是比较过去的样式,而且中国一直在特殊的文化背景怎样找到自己真正有关当代艺术实验真正的文化内涵这是显而易见的。

第二点我觉得今天的艺术家出场和过去有了很大的不同,方力钧是具有综合素质的人,如果方力钧能够把这点放大在文化上、时尚方面保持高度的敏感,我想这对今后他的作品而且对他的个人来说都是极其重要的。

我们横向对比一下英国当代艺术的崛起都是具备了综合素质,我想今后的中国当代艺术实验过程中艺术家个人魅力是一个非常重要的方面。这两种第一个是实验精神,第二个是个人魅力,使中国当代艺术在国际上面有比较好的开端。

刘淳:我想我对三位博士的发言非常感兴趣,尤其是邹跃进博士的发言是非常好的。

今天我们从社会学、人文学、哲学、政治学很多角度来介入图像的分析和研究,吕澎博士从社会学、汪民安从人文学角度谈了对方力钧艺术的看法。

我二十年前就认识方力钧,他的画不管是图像发生多大的变化,不管是画光头、水、花,他的画用两个词概括思想、立场。

图像是什么不重要,背后蕴藏的语言是非常深刻的,昨天我接受媒体采访的时候,他们让我谈谈方力钧绘画的几个阶段,方力钧的绘画不是几个阶段,而是几个序列,平时方力钧画序列,序列这个词不是我发明的,我用序列这个词非常准。所以我想方力钧的画没有阶段性,是一个序列,这个不同的序列里面一直贯穿着思想,一根筋过来就是思想和立场。

第二个问题昨天一个记者说你谈谈方力钧的崇高。

我说我看不到方力钧的崇高,我不知道方力钧哪崇高。我说只看到了方力钧经常给朋友买单,如果这也是崇高的话。

所以谈论方力钧是非常复杂的话题,其实今天的艺术就是在二十世纪初的时候杜尚把小便池作为艺术的时候,艺术已经模糊了,我们作为所谓的各种家,在方力钧面前和各种观众是一个角度。我们今天谈方力钧的画能够谈出很多问题,其实没有谁对,没有谁不对,还是让美术史去慢慢澄清,让美术史去沉淀。谢谢各位。

朱其:现在批评家的大部分职责是被各大拍卖公司主管、收藏家所担任,而且他们现在几乎肆无忌惮地在评论当代艺术,尤其是民生银行那个老总那段话有点刺激我。他觉得中国老一代评论家都不行了,新的一代都没有出来,他说我自己倒是在听艺术理论研究。

因为艺术市场到今天已经需要一个标准,到底什么样的当代艺术才是好的艺术。

所以其实这个确实需要批评界提出自己对当代艺术的看法,但是这个看法比较复杂,也不能完全说对也不能完全说它不对。

时间也不多了,我就说一个话题。

最近在想一个问题,从五四运动到现在其实没有一个人能真正从理论上或者语言上有真正系统的看法,其实也没有一个艺术家真正在艺术语言上有重大突破,包括文学都是这样的。

但是,我觉得文学界有一些个案,比如说像鲁迅包括延安时期的王实味,他有一种伟大的个人能量,那么我就从美术界来说,从徐悲鸿一直到后来罗中立的《父亲》,到刘小东的新生代和方力钧的“光头”包括到七零后的青春残酷。它是集体能量的个人呈现。

我们当代艺术三十年大概是这样一个模式,一个时代由于给一代人造成了压迫,内心产生了压抑和痛苦,然后这一代人里面比较聪明的有天分的人率先把这一代人的感觉干净利落表现出来,这里面有个人的因素,但是这代人里面的这些代表完全是个人的人格能量,我觉得不是,其实是代表这个一代人的。

比如说罗中立的《父亲》这个能量完全是个人的能量,实际上不是。比如说刘小东、方力钧,那个时期的东西完全是个人的东西,是一代人的东西,一代人通过天才的东西呈现出来。

最近很多人在转型,其实中国当代艺术需要一种个人能量的个人呈现。现在实际上也有很多艺术家往这个方面努力,这次方力钧的展览很多作品其实也体现了这种趋势,它的背景(天安门)象征意识形态的东西没有了,“泼皮”、“反叛青年”的东西没有了。

方力钧这个展览我今天看了一点觉得挺好,所有在明星艺术家里面方力钧的水平没有掉下来,他还在向前走,然后在语言、形式上还是有很多新的东西。这一步已经走出来了,这已经是很不容易的。

确实大家最近对明星艺术家的评价已经到争执不休的地步,但是也不能一概而论。我觉得方力钧的展览只是一个例子,他还在向前走。

李小山:今天会议在座的各位发表了很多非常有价值的议题,这说明针对某一个具体的艺术家和具体的艺术作品大家有针对性。

谢谢大家。

- 魔幻现实:方力钧艺术展策展思考——张晴

关于艺术家的创造性,在各种版本的艺术史中大书特书的,往往是艺术家对艺术样式与艺术语言的创造。回溯方力钧在近二十年的艺术探索,我突然发现,在如此近距离内论断艺术家的创造性是非常困难的。艺术家在每一个时段中都有着不同的思考与艺术诉求。在艺术史中幸运地留下名字的艺术家们,有的一辈子墨守一种艺术样式,有的甚至就只抱持着一幅“知名作品”,小修小补,惨淡经营。当然也有些勇者生命不息、颠覆不止,不断用心灵去感知社会与人世的变迁,及时做出新的判断与表现。随着社会的不断转型,他们的艺术思考与实践也与时俱进,所有这一切都具体地反映出艺术家内在的创造力和能量。

在1980年代,方力钧和当时中国所有富有抱负的探索性艺术家一样,接受了现代西方文艺思潮的影响,同时从中国的现实出发,揭示出文化本质的针对性,进而开始了他独特的图像营造。进入九十年代后,方力钧的艺术渐渐为艺坛所关注。第一阶段是所谓“玩世现实”,这是方力钧对当时自身的社会地位和社会关系进行的一系列视觉反思。经过不懈地调焦与定焦,方力钧用调侃的手法把自我生活的荒诞感描写出来,用夸张的和戏剧化的表现手法来表现自我、或一个个小人物打哈欠和怪笑的形象,以这些形象来嘲讽倾斜的社会世态与失衡的日常生活。从大的方面来说,这些形象是在嘲讽这个世界发生的风风雨雨,这个惊涛海浪难以平复的时代;从小的方面来说,他是在记录当时圆明园艺术家们颠沛流离的生活状态,艺术家们那难以控制的不稳定的内心世界。由此可以看出:玩世现实的实质是嘲讽对于自身的不安。所以说,在这个时段中,方力钧笔下的形象大都是自嘲与反讽。因此,方力钧式的嘲笑是具有两面性的:既是在嘲笑你,也是在嘲笑自己。这里面包涵着诙谐中的机智,自嘲中的自信,反讽中的犀利,就像一锅八宝汤一样,汤色和味道很难用一个词来形容,很复杂,很丰富。

方力钧那个时段所创造出来的艺术是具有多重味道的,可以说是最早的主动的“民生艺术”。那么,为什么叫它“玩世现实”呢?因为中国从来没有经历过真正的现实主义,近百年以来的中国文化史在现实主义之前套上了一个紧箍咒——“革命的”,这就诞生了“革命的现实主义”。现实主义在中国还没有扎下根,就立刻变成政治上的实用主义和宣传上的拿来主义,由此蜕变并速成了具有时代精神的革命现实主义,革命现实主义从此在中国文艺中变成了一个偏正结构。一路走来也算起承转合,只有到了九十年代,中国美术才逐渐孕育成了“玩世现实”,才开始展示出现实主义的另一个极端。方力均和他的同志们以纯粹且朴素的社会学目光,来刻画我们这个时代的轮廓和我们这一代人人生的表情,以诙谐的口吻贯穿了我们心灵与现实的屏障。

在2000年第三届上海双年展上,方力钧展出了的两幅大型版画,将玩世现实的精神与理念推向了又一个高峰。这是他创作中的一个重要转折。他作品中标志性的形象都是简洁明了的,如同写篇文章,只写一个标题就一目了然了,当简洁到了这个地步,方力钧的巨幅版画又回到了革命的现实主义宏大构图的模式中去借力,巨幅中成千上万的仰首人头,或痴呆、或木然、或无助、或盲然、或期待的满目人群,他们在有望中渐渐无望,又在无望中渐渐有望,这种错综复杂的心态变化,周而复始。方力钧敏锐且有力地揭示出这个时代的普遍性,以玩世现实的巨幅版画形式向社会表达出艺术家及时的判断与明确的态度,他是以这群远望天空来象征一代平民的集体情绪与共同境遇。这是纪念碑式艺术在当代中国艺术中的一个绝佳范例,方力钧以此做为中国平民跨入21世纪的现场,进行泼墨般的集体精神造像。

方力钧的第二个转折,就是画面中出现了一个飞翔在天空中的小孩子,这孩子趴在云朵上环视天空,呈俯瞰人间状。这就是方力钧进入象征主义的开端,云上的小孩子不仅仅是在一览众山小,而且是一种象征,象征着一种自由飞舞的文化灵魂,他脱离了所谓的客观的现实世界或主观的玩世现实,来讨论真实的与可视的现实世界,而是自己开创了一个多种视角的多元图像,在此图像中以象征为主线引领着天上人间、古今中外的想象在此相遇,并共同进入未知的领域。如同把杜甫的诗与李白的诗PS,抽离了现实和真实的本身,到了另一种想象的世界中来表达人对现实的幻想,人对人生的幻想,又从幻想作为起点再向上提升,一直升高到离开了李白和杜甫赋予的诗意,引领人们的心灵与想象一起进入象征境域。一旦到了此种仙境,就象李白的诗,怎么写也是对的,无法评论其是否现实与真实。我觉得这一时段方力钧的作品象他的人生一样,扶摇直上,他以一个天使的视角,俯视人间的春夏秋冬。如此,方力钧的心灵与视线似乎已附体在这个天使般的孩童身上,关照着这个社会,也关照着这个世界。

如果说方力钧画面中出现飞翔的小孩是从象征主义迈入魔幻现实的门槛。那么,在他的第三次转折中,方力钧真正地进入了一个辽阔无疆的魔幻现实世界,一个当代的神话世界。在这里,人与动物集于一体,日夜飞奔。古今中外的动物都有象征意义和使用规则,而在方力钧的画面中,苍蝇、蚊子、飞鸟、仙鹤、蝴蝶、蝙蝠、鹦鹉、金鱼、小孩、天使等从天南地北,纷纷齐心协力的一起奔向同一个方向。这让我反思一个问题,在芸芸众生之中,无论是人类还是动物,甚至是神仙,无论是高尚的还是卑鄙的,无论是灿烂的还是恶毒的,他们飞奔的方向是一致的。所有在人类的知识与记忆中的好恶,仅仅是人间制造,仅仅适用于人间。在这层意义的前提下,如果你觉得苍蝇蚊子是不好的,那么苍蝇蚊子也不会觉得你是好的。从朴实的生命意义上来说,人和动物都一样是具有生命的,其实神话与宗教中的神仙也是具有生命的,无论是人类、动物还是神仙,对生存与生活及其美好的未来同样具有理想与追求。如果是这样,我们岂能说出一只仙鹤和一只蚊子有什么区别?一个天使和一个魔鬼有什么区别?从佛教的观点来看,他们也是具有同等生命的。至于美和丑、善与恶都是人间伦理和道德的修辞,甚至美梦般的自我安慰。由此可以清楚看出:方力钧从玩世现实到一个小孩的象征主义,再到今日形成的人兽同舞的魔幻现实,逐渐形成了方力钧的世界观,即从形式上到认识上的演进,从态度上到思想上不断地提升,也是方力钧近二十年中对人生与艺术不断潜心思考与大胆实践的足迹,从这一角度而言,画面中的人与动物不得不高兴地离开地面,将人与动物拔高再拔高;才敢让小孩升上云霄,让所有的天使、苍蝇、蚊子、百兽飞向苍穹中共舞一曲,他通过各种天使与动物来象征和隐喻社会各阶层中的各色人等,把他们放在一个魔幻的天体当中同台表现。更为生动的是:有的孩子兴奋的骑在苍蝇和蝙蝠身上迎着灿烂的阳光,展翅翱翔,同时,有的孩子晕倒在仙鹤的身上昏睡也是迎着灿烂的阳光,展翅翱翔。在同一蓝天下的角色与行为如此巧妙的反串,不得不令人拍案叫绝,真可谓惜墨如金,力透纸背。方力钧以其特有的智慧激活了魔幻现实在当代中国文化语境中的生命与力量。由此,如若对应已经被魔幻过的现实,在画面中还有挥之不去的反讽,那也是褒义的反讽。

从理论上来讲,方力钧的艺术灵魂没有变,艺术立场没有变,艺术诉求也没有变。方力钧只是在思想上获得了一次又一次脱胎换骨,一次又一次在艺术图像上进行自我刷新和自我颠覆。那么,本次方力钧艺术展的学术意义即在于:通过超以象外的魔幻现实充分体现方力钧的艺术从态度向思想的转型。

历史总是选择具有创造性的艺术家,艺术家的创造也推动与捍卫了历史的完整性。方力钧从态度到思想的转型,不但是作为个体的艺术家所面临的现实,同时也是1990年代活跃至今的艺术家们共同面临的问题。近二十年以来,中国的政治与经济发生了根本性的变化,同时,文化针对性也发生了深刻变化。当今艺术家的焦点问题是:如何在国际艺术视野中去面对文化的选择与创新;如何面对国内外各色资本与艺术的现状与关系;如何面对独特的个人经历与经验所形成的人生观和价值观?因此,目前方力钧的艺术思考与探索就显得异常得清晰且生动,深刻且更为思辩。无疑,方力钧把目光转移到了在整个宇宙体内的生命体的基本属性和生命的本质,在此基础上,以诗一般的气韵和实事求是的精神来透析尘世中的真与假、善与恶、美与丑,并通过天使、婴孩、百虫的相互和谐的景致来交响出:人与神、人与兽、兽与神之间的共通性。这些神与人与兽的本质在魔幻般的图式中得以史诗般的展开与释放,使之在无限的空间中再一次群魔乱舞。此刻,你我只能站在魔幻世界的画卷中,以嬉戏的目光,观看神、人、兽们沿着同一个光芒万丈的前程,奋勇向前——

- 从玩世到自由:方力钧的艺术——吕澎

- From Cynicism to Freedom: Fang's Art - Lv Peng

孤立地问:“人如何对这个世界做出反应?”“如何评价人对世界的反应?”除了狭隘的心理实验,这样的问题没有意义。谁?什么时候?在什么地方?发生什么事情?什么样的反应?通常,人们讨论和评价问题要依据“准则”或被认为具有共同性质的“善”的标准,可是,在没有弄清楚前面几个问题之前,我们如何能够充满信心地说我们选择的“准则”与遵从的“善”是不可质疑的?

王八蛋才上了一百次当之后还要上当。我们宁愿被称作失落的、无聊的、危机的、泼皮的、迷茫的,却再也不能是被欺骗的。别再想用老方法教育我们,任何教条都会被打上一万个问号,然后被否定,被扔到垃圾堆里去。1

这是艺术家方力钧在1989年之后说出的话。这时,方接近三十岁,他生活在贫困的圆明园农村,他开始完成第一批具有自己特征的油画。按照他的说法,“很多闭塞、不顺畅的东西被冲得很顺畅”,他已经有了“海阔天空的感觉”2,按照字面上的惯性理解,这似乎意味着,艺术家获得了自由。不过,在没有上下文的支持下,我们很难将“上当”、“失落”、“无聊”、“危机”、“泼皮”、“欺骗”与“顺畅”或“海阔天空”联系起来,并且,如果我们仅仅带着对上个世纪“思想解放”时期的80年代的知识背景来阅读方的这句多少有些粗鲁的话,也难以对这位艺术家的精神状态进行评判,因为之前,尼采关于“上帝已经死了”的表述早已提醒了中国现代主义艺术家,对任何即定的原则与价值的怀疑精神已经具有合法性。那么,在90年代初,方力钧如此愤愤地——文字中的情绪与人们描述他玩世不恭的形象多少有些不协调——表达自己决不相信一切的态度,出自什么原因?

最初,心灵是一张白纸,尽管心灵的基因已经带上了承载心灵的肉体的遗传要素,不过,将一个刚刚诞生的心灵放在一个特定的环境中,所呈现的色彩与图画一定是受这个变化着的环境的影响的。方在很多年后说:人不存在抽象的先天的本性,本性是后天在社会中感染的。

方力钧生于1963年年底,这个干净的灵魂——以后它以婴儿的形式出现在构图里——出世的时间正值毛泽东在杭州召集部分政治局委员和大区书记参加小型会议讨论农村社会主义教育问题。会议的结果,产生了《关于目前农村工作中若干问题的决定(草案)》。这份政治文件强调了阶级斗争和道路斗争决定着“社会主义事业成败的根本问题”。方力钧的祖父是地主,1949年之后,这个身份意味着身份的承受者再也没有获得政治上的合法性。在一个阶级斗争越来越严重的背景下,地主3身份显然意味着是被斗争的对象。中共在不同的历史时期(例如抗战时期、要求与国民党组建联合政府时期以及1949年稳定政权恢复经济时期)策略性地利用过不同阶级或者阶层的人,但是,在由最高领导人独断决定方针、政策和国计民生的制度下,党内的不同意见与矛盾冲突将会以不同的政治与社会生活体现出来,只要政治斗争的需要,地主身份就随时可以不再受到任何理由的保护。没有涉世,方力钧对这个世界难以有清晰的反应,不过,他肯定无法逃离“四清”以来越发浓厚的政治空气。他的确是幼儿,他对社会问题还没有理性认识,可是,从1966年开始的文化大革命在“革命”的名义下出现的暴力与批判,一定会在这个幼儿的灵魂里刻下痕迹。现在,我们很难判断当他听到邻居的小孩呼喊“打倒方地主”的口号时究竟是什么心情(1967年),但可以肯定的是,那些声音所透露出来的情绪以及自家的后墙被人书写“方地主”的事实只能给方带来无法愉快的内心伤害。1969年,方力钧6岁。艺术家回忆说,这年他参加了一次红卫兵打击“万恶的旧阶级”的批判大会。他跟着人们高喊:“把他吊起来,这个老家伙!”可是,他马上发现,那个被人们批判的“老家伙”正是自己的祖父。在1949年以来的历次政治运动中,方力钧的这类经历远远不是独一无二。可是,在由血缘亲情所唤起的本能的“善”与社会环境所给予的否定之间,究竟应该如何判断?是“革命”比“善”更加符合人民的需要?抑或是应该接受“善从来就不存在这样”的看法?方力钧在“革命”、“武斗”以及模仿“厮杀”的环境和经历中长大。在他能够写出一些文字的时候,他也渐渐学会使用老师——实际上是那个制度——要求的文字:例如将工厂黑色的浓烟转换为天上的彩云,因为社会主义的国家风景要求歌颂与赞美。方力钧甚至有这样的回忆:“我现在想开放以前始终生活在互相仇恨、斗争中。由于出身造成的不平等,有时使我过早学会容忍或作假。如1976年,毛、周相继逝世。去灵堂悼念时,父亲对我使眼色,我知道我必须哭,但开始哭不出来,后来哭得不可收拾,所有的人都来劝我,老师表扬我。我知道如果我做出某种样子来,就会受到表扬。这些是从小被教育的结果,你所受到的教育经常与你认为的正确的行为相反,但我想我那时就很可能已经是一个‘两面派’了。这不是你愿意不愿意的问题,你的环境从小对你的压力太大了。”在这个时候,幼小的心灵学会了对善与恶的游戏转换,而不去理会在一个特定的社会里如何固执自己所理解的抽象道理。

事实上,方力钧的个人经历不足为道,他所遭遇的一切不过是大多数普通人的日常生活的一部分,在那个阶级斗争的年月,没有谁是安全和可靠的,保护自己的方式没有道德标准,因为,道德标准并不存在,或者说道德标准本身已经被阶级斗争的标准所完全替代。

为了躲避随时的不测,方力钧接受过父亲的劝导,学习画画。中学时期,他在美术小组和邯郸市群众艺术馆业余美术班的学习经历唤起了他对绘画的爱,并为之后的艺术道路奠定了感觉上的信心。

1980年,方力钧进入了河北轻工业学校,他可以在相对更加专业的环境中学习艺术。可是,最重要的是,这个年度已经呈现出新的语境。在之前的1979年6月,《世界美术》创刊,发表了中央美术学院艺术史教师邵大箴的《西方现代美术流派简介》,之前,西方现代主义受到了绝对的禁止和批判;《美术》发表了吴冠中的文章《绘画的形式美》,在1976年10月之前,“形式美”属于资产阶级的东西,同样是被禁止和批判的对象;8月,《连环画报》第8期发表了在政治上控诉“文革”的连环画《枫》,这表明人们可以公开倾诉内心的不满与反抗,可以公开地为自己的命运流泪。事实上,《美术》第8期迅速展开了对《枫》的讨论,人们对“真实”这个概念开始了更加富于思考的质疑与理解,对抽象的人性给予了温情的关怀;9月,袁运生等艺术家在首都国际机场绘制的壁画《泼水节——生命的赞歌》让人们吃惊,很快也引起了广泛的争论;尤其是发生在北京中国美术馆的第一届“星星美展”(9月开始)所引发的游行事件,给人们带来了震惊,因为“民主”与“自由”这样一些极度危险的词汇出现在了游行队伍中。在邯郸的方力钧与这一切没有什么关系,但是,这些背景为他以及其他学习艺术的年轻人提供了一种他们马上就能够感受到的全新社会现实。所以,在他进入轻工业学校之后,他能够有机会了解逐渐蔓延开来的现代主义艺术。这年3月,庆祝中华人民共和国成立30周年官方全国美展作品评奖工作结束,程丛林的油画《1968年X月X日雪》、高小华的油画《为什么》、王亥的油画《春》获二等奖。这些表现感伤与灰色情绪的绘画能够在官方美术展览中获得奖项,在于“文革”期间的“法西斯专制”受到了公开的批判。在迅速吸收知识的时期,方力钧从“伤痕”美术的作品中看到了对历史的新的态度。事实上,像罗中立、何多苓、程丛林、张晓刚、周春芽、叶永青这些四川美术学院的学生的作品以及他们发表出来的文字,还没有超越以后的所谓“现代语言”问题,可是,作品传达出来的感受是真实的和有感染力的,方力钧从小就表现出知性的敏感,所以他能够在“伤痕”、“乡土”与“生活流”的作品中——正如在陈丹青的作品中——感受到写实主义本身的魅力。中专时期的这些印象与感受,在方力钧的心灵之纸上与曾经的色点和符号再次交叠,也许一开始是潜意识的,但是,内心世界随着渐渐的交叠——来自社会、艺术和具体的经历——变得复杂起来。

方力钧有过一次重要的写生经历(1982年)。他与朋友结伴到太行山区的涉县写生。太行山的风景容易让人联想到“乡土”与“生活流”那样的作品,朴实与自然,但并不富饶。之后完成的《乡恋》、《无题》被认为与这样的环境和人物直接有关。水粉组画《乡恋》固然是那个时期流行风格影响的产物,可是,那自然环境所具有的朴实性仍然是打动方力钧的重要因素。可能,不是因为“乡土”风格有什么魅力。而是真实的乡土让心灵之纸那纯真而没有受到污染的部分渴望得到满足。在《乡恋(之二)》的构图里,温馨甚至感伤的情绪暴露出了已经懂得说假话的中专毕业生内心的真实向往。这组作品参加了第六届全国美展。这一定为那时的方力钧增强了极大信心,他至少感受到了真实的感染力,至于画中卵石与以后他的光头的潜在联系,却是潜在的和需要时日才能浮现出来的。

对西方著作的大量阅读是80年代青年人普遍的特征。在方力钧的回忆中,我们没有看到他对那些后现代主义思想有什么关注,他甚至也没有太多地去理解现代主义先锋们的晦涩的观念。他在回顾曾经的阅读经历时能够带着感情的部分是那些经典的和启蒙性的著作:

说到影响,我想谈谈那些曾经对我影响巨大的书:艾米莉的《呼啸山庄》、卢梭的《忏悔录》、雨果的《九三年》、欧文·斯通的《渴望生活》,还有《邓肯自传》,它们在最需要的时候让我全都碰上了。《呼啸山庄》中的三姐妹身居英国乡村,过着极其封闭的生活,她们的想像力和波澜壮阔的感觉完全来自内心,这使我明白真正的生活是用心去体会的。假若一个傻子,纵使万千事物排山倒海,在他内心也不着痕迹,那还是没有生活。《忏悔录》中的卢梭,年轻时与朋友领养一女孩,本想长大了一起受用。但随着岁月的推移,他们之间产生了真正的父女情感,最终没有把女孩当成玩物。卢梭并不矫饰自己,而是以那么赤裸的心态、那么朴素的语言把自己的肮脏事情说出来,他因而变得坦荡透明—这使我真正理解人性、人的自尊及人的权利。《邓肯自传》中传达的自由艺术的理想,那么朴素的表达方式,真是让我震撼。至今每当我笔下出现水的时候,都一直怀疑自己是否与当时书中描写的穿着白色图尼克的孩子,在蓝色的天幕前跳舞的景象有关。在我对每一个问题思考的关节,这些书都及时出现,它们真正震撼我的灵魂。4

如果我们将这些内心感受与之后方力钧高呼不要上当的玩世情绪进行对比,可以看到,一定有什么深深的伤害让他痛苦不堪。人类文明所滋润出来的知性是恒定的,这种恒定性与人天生应该有的道德感是相吻合的。重要的是,一种特殊的制度环境可以将人类普遍的道德感或善良意志与人自身的需要分离开来,为着一个外在于自己的目的或者抽象的理想,尤其是在一种理想被强制性地确定为所有人的共同意志时,恒定性、道德感以及善良意志便不复存在。可是,当方力钧有机会读到那些呼唤内心自由的文字时,他得到的收获是巨大的,这个收获不仅是增加了知识,而是对内心本来就存在着的纯洁性给予的有力认同。既然有这样的收获,为什么一定要去理解那些艰涩的哲学与观念呢?所以,没有什么明确的文献记录表明方力钧对抽象的哲学著作有多少兴趣,而在80年代,这样的兴趣正弥漫于50年代出生的大多数现代主义艺术家的内心。

顺向至极端的抗争性格是那些不能通过权力和其他社会资源来保护自己的人所经常表现出来的特征。在幼年,方力钧没有能力和胆量将那些呼喊“方地主”的人赶走,他只能默默地目睹这一切,通过游戏打斗来消除内心的压抑;他不能说内心的不情愿是真实的,而要通过假哭来争取人们的认可与同情,以至那样的假居然能够臻于极致而给人真的感觉;到了中专,学校的纪律让他感到是内心自由的桎梏,可是,他不能够反抗学校的明文规定:男同学的头发鬓角不能超过耳朵,结果,他与同学们干脆剃光了头发,他显示的是,我可以做得更地道和更干净。这是一种反抗的形式,可是,这种反抗是在牺牲自己的自由的情况下,通过自我否定的方式来重新获得新的自由的努力,是一种人生过程中对困难的理解与处理方式。当这样的方式在内心刻下了深深的烙印时,就会产生难以磨灭的记忆和情绪爆发。对于方力钧来说,记忆与爆发是同时的:“从那个时候开始,光头的形象,在我的潜意识中就有了一种叛逆或者带有调侃的意味”(方力钧),“潜意识”是记忆资源,而“叛逆”和“调侃”是爆发的形式。

《乡恋》完成于在邯郸市广告公司工作时期,也是在1984年,方力钧游历南京、上海、广州参观第六届全国美展,很快,他就辞去了广告公司的工作。1985年,方力钧进入中央美术学院版画系学习。大学期间,学校内的严格教学与校外的新潮艺术所形成的空气,让已经享受到了自由的方有了游刃的学习和生活空间,他与他的同学们可以任意选择阅读的对象、学习的方法以及生活的方式。大学期间,方力钧有条件在不同的资源之间来来回回,思考、选择并实践各种可能性。直到1988年,方力钧画了他最早的“光头”作品。这批作品是以素描的形式呈现出来的,而人们可以看到,方的素描方法与中央美术学院的契斯恰可夫体系没有太大的关系。圆乎乎、光溜溜的处理方式与强调块面与结构的学院方法区别太大。

1989年2月,方力钧将他的素描送进了在中国美术馆举办的“中国现代艺术展”,可是几乎没有受到人们的注意。那个迟到的现代主义聚会过分混乱和嘈杂,人们在眼花缭乱和让人震惊的枪声中没有闲心去观赏墙上的作品。最为重要的是,从1987年的“反对资产阶级自由化”的政治运动开始,现代主义的内趋力开始衰落,本质主义的问题已经暴露,可是,1988年混乱的社会空气暂时遮蔽了这个问题,直到1989年的展览开幕,事实上的“后现代”——放弃本质主义立场的言行——已经出现,像展览中王广义的《毛泽东》、吴山专的《卖虾》、李山的《洗脚》以及张念的《孵蛋》,以及匿名恐吓信、避孕套、企图用大绳拉走美术馆的呼声,直至萧鲁和唐宋策划的开枪等等,共同构成了部分批评家感到担心的问题。方力钧的“光头”肯定与丁方、舒群、毛旭辉的形而上的理念没有干系。方力钧不是’85美术新潮队伍中的成员,不过,他开始准备进入这个看上去好象要继续行径的队伍,他拿出自己的有乡土气息的“光头”给那些前卫批评家看,却没有得到充分的关注。方力钧自己似乎也没有特别的信心:他说“光头”“是无意之中画的,所以它的整个场景是设想的,就像写实绘画的涉县农村,那么当时的光头啊,人物形象上的重复使用,都是一种尝试,它含有一些因素,但是没有变通的办法,没有把它发挥的信心。”5 可以肯定的是,无论“光头”在之后是否有了辉煌的影响,可在当时,方力钧并不以为“光头”有什么艺术上的用处。

1989年政治事件让世界震惊,一个让人无法回应的事实再次出现在自己的面前,应该如何去面对?在潜意识的积淀中,方力钧已经有了遭遇强大暴力的记录,现在,他亲眼看到直接对抗的失败。无论在当时是否能够从理论上归纳出这种本质主义的对抗方式如何无效,他也在内心里很自然地有了退让与顺向抗争的路径。他感受到个人力量的渺小,也感受到了个人自我拯救别无选择。现在不是讨论谁是谁非的时候,甚至事实上也很难说清对抗双方的是非,那是一个更加宏观和超越个人的问题。他本能地要求自己:必须自己来关照自己。何况,此时的方力钧已经开始为自己的生计在奔波和考虑。他也只能如此。所以,7月,他搬入了圆明园和颐和园之间的“一亩园工作室”,这里的生活很便宜并能够有助于自己的绘画,即便如此,他在继续完成素描和最初的油画的同时,也于次年的第一天被强迫搬迁,到了挂甲屯农民住的院子。这一年,他和他的朋友们(于天宏、陈红、田彬、杨茂源)想方设法通过贩卖明信片和绘制军用教学图维持生计。夏天,方在圆明园相对稳定地找到了一个自己的工作室。他的黑白油画《第一组》就是在这里完成的。

方力钧再次从内心里开始退让,他之所以觉得在1989年夏天之后内心“有一种海阔天空的感觉”,是因为紧张的对抗的无效再次唤起了他内心里迎面而去的力量。在之前的素描中,他本能地接受着对象的引导,淳朴的风景与农民(《素描(之二)》1988年),那时,他也将朴实的农民的牙齿画得清清楚楚,将憨厚——多少带有暧昧与善意的狡诈——给予了重复性的强调。可是,他还是觉得他要说的话没有说清楚,尽管这些生活中的特征符合他的本性。他很本能地就躲避了“焦虑”、“压抑”以及“拯救”的心情。有时,他将人物放在不同的距离(《油画(之三)》1989-1990年),观察在那个阴郁的环境里诡异的情景,可是,这似乎仍然不是他的目的。在1989年到1990年之间,在他的素描和色彩作品里出现了一个戴眼睛的女孩(《素描之四》、《无题》1989-1990年),这可能是他对自己的情感生活的记录,因为,在作品里我们能够很清楚地看到他自己。在《素描(之四)》里,艺术家夸大了前面女孩的体量,或许是一种强烈的夸张的透视所至,而他本人却安静地守候在女孩的一旁。不过,我们可以在构图中看到也许应该是太行山里的农民的重复形象,他们跟随在艺术家的后面,当然,我们也可以说,艺术家在构图中保留了他的眷念。不过,他在素描里强调了光头形象,因为“光头”能够给人强烈的印象;他也在作品中给出一丝暧昧的情绪,这多少会调节人们的感受,而脱离他们在流行的现代主义作品经常看到的压抑;他重复着一个人的头像,他让重复本身去再次强调特殊的个人情绪。这些因素在以后的作品中经常出现,并被放大成了一种将被命名的典型趣味。直到《素描(之五)》,方力钧将人物放在了更为宽阔的背景中,天安门广场的宽阔和不久前所体现出来的无边无际,也许提示着方彻底脱离太行山的石墙,脱离狭隘的、具体的环境,无论怎样,打开心扉可以获得“顺畅的”感受。方力钧将自己的反叛经历、太行山农民的形象、以及他对现代主义立场的远离结合起来,他开始清除画面多余的细节,而重新规划全新的形象。很快,方力钧在《油画(之四)》(1991年)里提炼出自己未来的方向。按照方力钧自己的陈述,这件作品的重要性在于他选择了“光头”作为他彻底的开始。很快,经过了一组黑白油画的实验,艺术家解决了油画材料带来的技术问题,他开始了典型的“系列”组画。

1991年3月,批评家栗宪庭已经开始将刘小东、方力钧、刘炜、王劲松、宋永红这样一些艺术家的艺术进行归纳,并开始使用“玩世现实主义”这个词。1992年,弗兰(Francesca Dal Lago)、埃利克策划的“刘炜·方力钧”画展和汉斯(Hans van Dijk)策划的“中国前卫艺术展”让人们看到了方力钧的那些经典的作品。批评家开始了对新的艺术现象的解读。在1992年的“方力钧、刘炜油画展”的目录文字中,栗宪庭这样来描述方力钧的作品:

方选择偶然、平庸、无聊的生活片断作为艺术语言特色的第一层,其次把画中的人物剃光了头,构成他艺术特色的核心,所谓泼皮,更多是从这里表达出的。其三他多把非诗意的无聊形象置于蓝天、白云、大海这些诗意的环境中,造成一种荒诞的气氛。他1988年毕业于中央美院版画系,有着不错的素描功底,油画不是他的专长,却使他找到一种和他心态、感觉对应的技法,即强调中性和非表现性的类似广告的画法,反使画面达到一种冷漠气氛。他的色彩也是非油画化的,大面积生猪肉般粉色和其他色彩的对比,一种非生命、非生活化的感觉,同样加强了作品的荒诞效果。6

画于1990—1991年的“系列”组画开始了被表述为“玩世现实主义”的旅程,画中人物百无聊赖地打哈欠、冷漠地凝视的表情很自然地让人联想到栗宪庭所分析的问题:

所有敏感的艺术家几乎都面对一个共同的生存难题,即生存的现实被以往各种文化、价值模式赋予的意义,在他们心中失却后,统治他们生存环境的强大意义体系,又不因为这种失却而有所改变。但在对待这个难题上,泼皮群与前两代艺术家发生了根本差异,他们既不相信占统治地位的意义体系,也不相信以对抗的形式建构新意义的虚幻般努力。而是更实惠和更真实地面对自身的无可奈何。拯救只能是自我拯救,而无聊感,即是泼皮群用以消解所有意义枷锁的最有力的方法。而且,当现实无法提供给他们新的精神的背景时,无意义的意义,就成为他们赋予生存和艺术新意义的最无奈的方法,和作为自我拯救的最好途径。7

栗宪庭提示的是一个真实的历史情景。作为这个历史情景的体验者与记录人,方力钧通过对自己的精神状态和表情的记录,将这个时期的中国社会尤其是北京这个城市的典型市民精神状态描绘了出来,的确,任何熟悉这个时期文学领域的变化的人都能够发现,方力钧作品中所体现出来的情绪的确很容易联想到说“别把我当人”的王朔的小说。当人们理解并认可了方力钧的艺术时,他们也开始理解了方力钧所说的不愿意上当究竟是什么意思。

面对自己无能为力的世界,方力钧理性地采取了自己的策略,他将世界反向打开,即让自我成为世界,就像艺术家邱志杰在1993年的一个表述:“每一个笼子都把它之外的世界关闭在它之外。”8 尽管这样的态度缺乏出发点的参照,但是,艺术家一开始就本能地、甚至也只可能如此地来面对自己的问题。在生活中保持自己光头的个性特征,与在绘画里通过对光头的描绘来表现无个性似乎获得了某种同一性,艺术成为生活的写照,生活成为艺术的一部分。方力钧以后的作品都是沿着这样的路线演变。在消除了细节之后,方力钧认为他进一步实现了自己的想法,很多年之后,他解释了他为什么如此地重复“光头”:

对于我来讲,光头的重要性是取消了某个人的概念,把整体的人这个概念展现出来,而这会更强烈。在艺术史,很少有艺术家把共性的人拿到前台来。可是共性的人的量往往是铺天盖地的。9

方力钧开始迅速受到关注。汉斯在柏林世界文化宫中国当代艺术展。1993年,他参加了栗宪庭、张颂仁策划的香港“中国后八九”艺术展;这年,奥利瓦(Achill Bonito Oliva)访问了方的工作室,并邀请参加“东方之路——威尼斯双年展”;美国《时代周刊》刊登了方力钧大幅的工作照片;艺术家的作品《第二组 2号》刊登在美国《纽约时代周刊》;他开始访问中国艺术家向往的欧洲——他从西班牙、意大利、德国、法国等国家的大量美术馆中第一次真正接受了西方艺术的洗礼。无论怎样,他感受到了成功的喜悦,即便那些欧洲艺术家的风格并不都是自己真正喜欢的东西,他还是在这样的盛宴中体会到艺术的滋润。

1992年,邓小平的“南巡讲话”保证了市场经济的继续发展,他告诉那些自从1989年以来再次强烈地提示资本主义危险的人们,不要再讨论姓“社”和姓“资”的问题,“发展才是硬道理”。在这样一个一党执政的制度下,拥有真正威望与影响力的领袖人物只需要一句话就可以改变政治与社会的空气甚至历史格局。这个被称之为“南巡讲话”的核心是:意识形态的争论没有意义,如果国民经济不能够迅速稳定和发展,这个国家和民族的未来将被葬送。关闭讨论的现实对于冲突的双方都不是愉快的,可是,对于那些认为讨论真的没有必要的人来说,这无异于一种打开,甚至无异于一种解放。这样的情况多少可以在“后现代主义”对“现代主义”的消解逻辑上可以找到共同之处:本质主义的追问难道真的有结果吗?方力钧和其他一些艺术家说,我们在自己的空间里自由的伸展手脚、自由地呼吸空气、自由地嬉笑、发呆,或是自由地打着自己的哈欠,这样的行为可以吗?会成为一种被攻击的姿态吗?充满了无聊情绪的光头形象可以被理解为对现实体制的嘲讽,但是,从作品光头形象多选择艺术家的朋友和艺术家自己作为模特儿的事实来说,从我们对那个特定的历史语境的分析中,我们可以看到,自我嘲讽是方力钧这时的作品的真正内涵,艺术家是通过假设自己的空间才是真实的自由世界的前提下,对他没有能力应对的现实的一种并非没有立场的逃离。当《系列二(之二)》(1991—1992年)被发表在1993年的一期美国《时代周刊》的封面上时,那个事实上是以朋友于天宏为模特正在打哈欠的光头形象,被配上了一句充满意识形态含义的标语:“这个吼叫能拯救中国吗?”1993年的西方世界对中国的未来没有信心,他们怀疑在不久的将来中国有可能全面爆发危机。西方人当然能够看出那个巨大的“哈欠”的问题,所以,也才使用了问号。可是,很少有图像能够像方力钧这个“哈欠”那样体现出磨棱两可的状况,这给予了人们多种解读的可能。

批评家栗宪庭以后又为这样的“两可文化”寻求历史支持:

玩世、泼皮幽默作为一种在精神上自我解脱的方式,不但是后’89时期的一种标志,甚至作为中国知识分子的一种传统方式,可以在中国历史上找到许多例证,尤其政治高压时期。如魏晋之际的士大夫,多以狂士自嘲,并以放浪形骸的生活作为对付高压政治的方式,来达到自我解脱的目的。当时的名著《世说新语》多有记载,如《任诞篇》:“刘伶恒纵酒放达,或脱衣裸形在屋中,人见讥之。伶曰:我以天地为栋宇,屋室为裤衣,诸君何为入我裤中”?阮籍更宣称“礼岂为我辈设也”?遍阅元代散曲,此类作品更是比比皆是。如关汉卿:“我是浪子班头……半生来弄柳拈花,一世里眠花卧柳……天与我这几般儿歹症候,尚兀自不肯休”;周仲彬:“问甚鹿道作马,凤唤作鸡。葫芦今后大家提,别辨个是和非”;刘时中:“浮生大都空自忙,功也是谎,名也是谎”。明沈括的《梦溪笔谈》谈及这些元文人时说他们“皆有滑稽无赖之作”,明孙大雅在《天籁集序》中论及当时曲作家白朴时也用了“玩世滑稽”这个词。因此,这种以放浪、泼皮的方式表达的无聊感与虚无感,是中国士大夫历来对政治黑暗的一种逃离方式。我们从近代知识分子林语堂等重提放浪及90年代泼皮幽默的艺术思潮中,再次看到这种相似的方式,不能说是一种偶然。甚至我们从最具大众化和中国特色的大肚笑面的“弥勒佛”的造型的形成和流行中,看到一种玩世是如何深入中国人的骨髓,“开口常笑笑世间可笑之人,大肚能容容天下不平之事。”从弥勒佛的笑到方力钧创造的泼皮的笑,我似乎看到某种联系。10

可是,正是这样的对进攻的放弃,使得方力钧等“玩世现实主义”艺术家的艺术与王广义等人的“政治波普”构成了反省现实的双向力量:前者更多地强调了个人的自足性,而后者将历史形象与当下符号重新拼接,他们共同完成了对本质主义立场的消解,为之后出现的艳俗艺术和彻底而自由地利用历史图像资源开启了道路。

1993年,方力钧开始将水最为表现的重要内容。我们可以在早于1989年到1990年期间完成的作品中看到水的出现。在两幅“无题”的作品里,我们清晰地看到了宽阔的海水,只是,在有女孩的这件作品里,浪漫的心情好像是画面给出的情绪;而那件高举双手的构图看上去更多地也是一种特殊心情的记录。在“系列一”组画里,水是如此不可阻挡地试图进入方力钧的绘画里(《系列一(之三)》、《系列一(之四)》、《系列一(之七)》(1990—1991年),所以,在“系列二”的“之十一”中, 作为艺术家的“光头”已经即将进入水中,而水中的女人成为一种事实上的诱惑提示。

1998年,方力钧在给学生介绍自己的作品《油画之四》时谈到了关于“光头”与“水”孰先孰后的原因:

这幅作品对我来讲是特别重要的作品,因为这时我面临选择:一个选择光头的形象,一个选择更感兴趣的水的作品。画水的话,我可能画出非常有意思的画,但是视觉效果不会强烈,对于年青的想引人注意的画家来讲不够,顺序有问题。最后决定先画光头,选择醒目的符号,把水的感觉留到以后来画。另外一个,当时版画系不鼓励画油画,画水的题材,技术上更困难一些。11

然而,正如传统文字表述的那样,水的象征性质是难以简单言说的。对于方力钧来说,水首先是一个困惑,就像他早年的经历所给予的提示一样,方对上小学前误入深水池嬉水,险些淹死的经历记忆尤深,以至被转换为持久的潜意识因素:“那个池子足有几米深,我立刻乱了,不知慌乱中怎样上了岸。这件事对我的影响很大,使我直到大学二三年级时才学会在水中轻松自在地游泳,也使我以后又可能领会通常‘碧波荡漾’的多重意义。” 对水的控制能力让自己充满喜悦与自由,当“水”以海水的面貌呈现出来,便象征着内心的辽阔与自由,就是艺术家自己说的“顺畅”或“海阔天空”。到了1993年,方力钧终于可以大胆地跳进水中,他觉得他真的自由了。当然,一开始,方力钧在技术上不是没有顾虑,因为他很早就知道了对水有特殊理解和表现的霍克尼(David Hockney),那时,他既担心水的形象不强烈,也担心自己在技术上难以处理水的复杂性。他将自己风格的建设课题首先放在了对“光头”的利用与表现上。正因为如此,方力钧在之前涉及水的表现上犹犹豫豫:

\但后来我想通了,第一,霍克尼的水对中国人的感觉来讲有点简单化了;第二个理由,如果害怕和他重复就等于说我是在碰运气,缺乏发展线索的。12

他告诉听众,艺术工作也像乘坐火车一样,虽然一开始不同去向的乘客是在一列火车上,可是,随着火车的行进,每个人都会在不同的地方下车去自己要去的地方。因此,艺术家不再顾虑自己是否可以达到自己的目的。方力钧关于艺术风格之间的关系以及所谓独特性的理解与王广义等人的表述不同——后者在80年代后期就从贡布里希(Ernst Hans Josef Gombrich)的“图式修正”理论中看到了“原创”的不可能性,但是,他们都承认联系的必要性,并且艺术家不应该为某种联系——无论是题材还是方法——而伤脑筋。很快,方力钧就能自由地将水作为构图的主题。我们知道,1993年是艺术家心情舒畅的一年,他不仅可以自由地跳进水中,而且还可以在水下利用水下照相机观察物体(人)在水下的情形,他将这样情形表现出来,唤起人们的同情。水是一种简单的物质,可是,水的意义从来就是“两可”或者多重性的。按照中国古人的政治学理解,水可以载舟和沉舟;但是,如果我们尊崇道家的看法,那么,还有什么物质比“水”更能够让我们感到力量与永恒呢?没有任何力量能够抵挡水的行进,水可以冲开阻挡,也可以绕过阻挡,当然可以溢出阻挡而向四周无限蔓延渗透。方力钧几乎是本能地这样去理解水的性质的,并且将这样的理解贯穿在他的其他作品里。所以,他相信人们不会将他的水与霍克尼的水进行无聊的对比。当然,对于那些将水看成是危险的人来说,水也是漂浮不定和深渊的同义词,有时候,方力钧的内心会产生种种不安与困惑,这时,他笔下的水也是一种不详的预兆。实际上,方力钧在水中放置了复杂的元素:自由、危机、达观与悬置,甚至性爱,如此等等。这时,我们也能够回想起艺术家早年的《无题》(1984年)中迷惑人的光环和波浪般水平线所蕴涵的情绪:无限、深渊以及没有终止。以后,我们可以看到,这样的心惑延续到了将抽象的光环与曾经不断出现的人物与花朵结合起来构成天穹的未来。

早在《系列二(之八)》(1991-1992)里,我们看到了脸部充满细节的温情,女人身着花布衣裳,这迎合了最民间的态度和涉及性爱的双重趣味(在《系列二(之十)》里女人衣服上的图案并没有透露出太多的这类气息)。女孩衣服上的花朵被富于耐心的笔触描绘出来,说明“花”一定有其象征性的作用。不同开放程度的花出现在1993年的许多作品里,她们以一种艳丽而多少邪恶的方式飘散在构图里。对于五六十年代出生的人来说,他们非常熟悉“花”的象征意义,“祖国的花朵”这个表述构成了他们的历史记忆。1993年,也许是某个契机的诱发,方力钧开始使用鲜花,巨大、盛开以及四处飘散加强了“光头”的放肆与俗气。可是,如果从以后对花的继续使用和与红领巾的结合来看,我们看到了“花”在方力钧内心里的复杂性。与对“水”的表现一样,“花”的表现与含义同样来自早年无意识的积淀,1998年,在介绍《1993.1》(1993年)时,方力钧说:

这是教育的结果,我们从小被教育:充满了鲜花啊!幸福啊!很长时间我自己都不清楚为什么老画花,对花特别感兴趣。这组作品时间特别早,比老栗说得艳俗早很多,我回忆可能是这样一个故事:读中专的时候,在唐山学陶瓷美术专业,有一次我们上花卉写生课,老师教我们如何用颜色把花画得美,画得好看。上课的时候教室窗外面有游行的汽车、人流;接着我们就听到枪声,在离我们不远的地方,课间休息时我们跑过去,到河边的时候已经没人了,河边儿一滩血。平常我们在那个土包边儿玩,画写生,不知道那个土包是干什么用的,现在发现那个土包是枪毙人用的,离学校很近。我想可能是这样一个原因,这样一件事对我影响很大,老师教你如何用好看的颜色画好看的花,同时窗外有人被枪毙了,这个人可能是应该死的,也可能是不应该死的;无论如何是一个生命死了。13

在日常经验里,鲜花盛开的含义与一个具体生命的消失的结果是不相称的。尤其是在早年的社会主义记忆的年月里,鲜花与美好和希望有不可分割的象征性联系,并且具有不可质疑的意识形态特征。方力钧决定将鲜花的含义推向极端,让她们彻底妩媚艳俗。人们曾经对美好的鲜花给予重视,并希望鲜花具有完美的效果,现在,艺术家决定通过艺术彻底地进一步成全这个愿望,结果是,我们很难相信鲜花内涵的真实性,在嬉皮笑脸和没有边际的海水的呼应下,我们发现了鲜花的空洞与虚假。

方力钧关于花的油画参加了1993年威尼斯双年展,他与其他中国艺术家的艺术开始成为国际领域熟悉的对象。我们知道,对于中国当代艺术家来说,1993年的威尼斯双年展具有转折性的象征意义,敏感的人认为,中国艺术家开始被国际社会所接纳,未来充满希望,尽管这次双年展受到了部分批评家的质疑——他们提醒艺术家注意“后殖民文化”的问题,不要使自己的艺术成为西方意识形态策略的工具。可是,正是1993年的威尼斯双年展,使方力钧成为在西方社会艺术系统中最具代表性的中国艺术家之一。他的作品中造型、色彩、技法所构成的审美态度得到西方批评界的认可,除了具有风格和形象独特性——一个特定时期的形象象征——方面的原因外,另一个重要的原因的确是,它们吻合了后冷战时期所谓东方和西方的意识形态对峙,它们符合了这种意识形态游戏的基本规则——无论这游戏是认真的还是随意的,是政治的还是审美的,是学术的还是商业的,是个人的还是权利集团的。这次双年展之后,方力钧陆续参加了众多的国际性展览。

对圆明园工作条件的不满意,圆明园本身的喧哗与问题重重,使得方力钧与部分艺术家决定更换他们的工作与生活环境。1993年冬天,方力钧与张惠平、岳敏君、刘炜将画室迁移到了通县宋庄小堡村。这次迁移是选择的结果,它意味着方力钧波西米亚式的生活彻底结束。可是,工作条件的改变并不意味着艺术工作会有什么收获,不过是新的生活环境有了变化,之前的经历和带来的信心给予艺术家更充分的思考余地。从1995年起,方力钧开始实验版画的可能性,他在中央美术学院的专业就是版画。可是,对于方力钧来说,版画仅仅提供了材料与方法上的可能性,版画也许在视觉上没有油画更具有打击力,但这不意味着不会产生新的效果。他保留“光头”与“水”的主体成分,用巨大的尺寸来保持视觉冲击力,用工业电锯来制造新的效果,而黑白灰的构图则将自由的实验控制在一种事实上很温和的美学态度范围内。因为对版画的开放性理解和对工具的从容利用,他在版画的制作上保留了特殊的形式趣味,在很大程度上讲,版画实验不过是艺术家希望扩大可能性与尝试增加趣味的艺术工作中的一部分。

直到1997年,方力钧都在思考如何在已有的基础上展开自己的艺术。他尝试过很多变化。他将人物的形象隐藏在水中,让他们若隐若现。我们的基本经验是,无论是在水中观看水中的形象,还是从外观看沉潜在水中的形象,我们都很难把握观看对象的精确性,当水的晃动与深浅发生变化,当我们的观看距离没有确定性,当对象处在不同的光影环境中,我们会产生迷离恍惚的感觉。视觉导致的印象可以影响我们的情绪,因为我们看到的东西会导致我们联想。艺术家自己陈述说,从1996年开始的一些作品属于对“记忆”与“遗忘”进行探讨的实验。按照这样的出发点,人物形象用模糊的方式来处理,也许可以提示时间问题?一开始,艺术家似乎觉得最能够提示时间问题是接近金黄色的气氛,尤其是在1997年的那组作品里的色彩空气,足以让我们回想到1984年的《无题》和《乡恋》,差异是,十多年后的内心温情不再是具有装饰趣味的光环或者具有乡土气息的乡村环境。在《1997.4》和《1997.5》中,我们很难判断那些漂浮在水中的形象是今天的成人或者是曾经的儿童。水上水下,黑白彩色,油画版画,方力钧在不同的实验中来来回回。在这个时间不短的实验阶段,方力钧没有像过去几年那样,能够直接表现要表现的对象。他希望在更为抽象的问题中寻找作品的出发点,他试图用金光灿灿中的模糊形象来告诉我们:我们的今天是在对昨天的回忆,但我们又不能够保证在其确定性的基础上呈现出来的。这个逻辑产生的结果,是一些模模糊糊的构图,我们能够看到那些被确定的要素——光头和水;我们甚至也能够看到趣味上的变化——弥漫着金黄色空气的构图,但是,我们是否真的能够将艺术家的出发点与作品的效果联系起来?

寻找记忆的实际内容在1998年的部分作品中呈现出来,在《1998无题》或《1998.8.10》里,红领巾出现了。众多的形象不是成年人,而是到了佩带红领巾的青少年。使用光头青少年的形象可以被理解为艺术家对自己过去时代的记忆,如果在欢呼雀跃的场面里还伴随着鲜花开放,我们就很容易确定其时间与时代的上下文。那个曾经在美国《时代周刊》上被理解为“吼叫”的形象又一次出现在构图里(《1998.8.10》),基于这个形象处于红领巾与鲜花的氛围里,我们更愿意将其理解为今天对昨天的自己的回忆。在这样的作品里,艺术家很难去进一步解释昨天的一切与今天是什么样的关系?红领巾与鲜花的历史关系究竟如何?不过,将这样的历史符号还原出来——艺术家甚至将今天的形象放在了后面,对记忆的解读就已经获得了多种可能性。重要的是,艺术家在自己的构图历程中给出了问题的阶段性转折:通过红领巾、曾经的欢呼情景以及鲜花的四处飘散来归纳今天与昨天的关系,并在构图中呈现出来,观众可以有无限的解释,他们不会再因为构图的模糊而根本就停止不前。

五六十年代出生的人有很多观看彩色气球升腾的经历,在国庆、在重大政治事件、在特殊的庆典活动,那些升向天空的五彩气球带走过无数的理想与遐想。不过,记忆中的那些升腾与五彩缤纷的场景几乎是意识形态活动的一部分,不断的重复和强调,最终成为一代人甚至几代人的永恒记忆。方力钧在构图中放置了升腾的鲜花,以勾起人们对过去的记忆,为了让这样的记忆有还原的性质,他不仅更强烈地表现仰视的构图,他甚至干脆让青少年升向空中。这样的结果是,艺术家不仅更多地让我们仰望天空,也干脆将我们也带向了云端(《2000.1.10》、《2002.1.3》、《2002.2.15》),带向了高高的山峰(《2002.6.4》、《2004.1.2》),最终,记忆问题本身被置后,艺术家改变了升腾前制定的计划,到了高高的空中,他要求人们与他共同来俯瞰这个世界。我们看到,艺术家再次将抽象的问题提出来,与几年前的情况不同的是,他提供了新的构图和世界观。到了2005年,艺术家在云海中重新构织欢乐,他取消了红领巾,保留了青少年的形象,他们在无边无际的云海里欢呼雀跃,却没有任何实际含义的指向,那些茫然的欢乐在十分肯定的描绘中营造出巨大的荒凉与空虚。所以,在情绪和精神内容上,艺术家在十多年后完成的绘画接续了早期“泼皮”、“玩世”的问题,只是,在这时,艺术家已经不再去关心个人的日常状态,他提出的是我们大家面临的问题:历史上的我们与今天的我们究竟是什么关系?艺术家改变空间结构,利用不同的透视关系来调整我们的视觉习惯与观看方式,在方法上,他采取了象征主义的寓意,他试图在平面上也表现出时间的概念:

我把云层拧过来,拧成了一个隧道,变成了一个空的,一个大洞了,你从任何一个点上看,它都是写实的,一层一层推过去的云彩。从那个地方,也是一层一层推过去。而且画可以从四边看,你怎么挂都行。这个时候它就变成一个空间和时间都有的东西。绘画里面很容易造空间,但你不能造时间,我把平面给拧成圆洞,简单地说就是一个下水道了。这下水道有人离得近,有人离得远,这个时候它自然就会产生时间意念了。不仅仅是视觉上的空间的概念了。这个时候,人只能琢磨,你得改变一个方式,你不能再按照站在泰山上面看云海,或者站在北戴河鸽子窝上看日出,它已经不是这样一个概念了。它把惯性的透视方式改变了。但是,你越局部看,它越真实,每一个局部都是跟你的惯性的方式一样,每一个局部都是符合你的常规的透视习惯的。可组合在一起,却变成一个完全不一样的结构。14

早在1996年,艺术家完成了一件标题为《1996.9》的作品,在这件作品里,人物形象已经不再是作为成年人的光头,而是儿童。艺术家放弃了对生存状态的表现,而将目光放在了人的生命成长的初期。1997年,青少年模模糊糊地出现在金黄色的记忆海洋;1998年,他们佩带着红领巾复活在鲜花与欢呼中,到了2000年,他们升向天空似乎是提示古老的理想的力量。

对于方力钧来说,对记忆的表现不是来自文学的提示,之前他通过朦胧模糊的构图来探讨过去,可是,既然绘画的探讨仅仅是一种知识与文明赋予的假设,那么,寻求更为清晰的表现也许能开启新的可能性。所以,他渐渐将完全没有涉世的儿童作为形象的主题。这样,艺术家可以邀请我们共同探讨不是个人,而是人和与人有关的生命问题。可是,不同阶段的生存状态之间难道没有共同性吗?难道初生的婴儿就没有遭遇问题吗?婴儿出现在两指之间(《2000.1.5》)以表明他能够存在的条件;出现在水中(《2004.6》)以提示我们生命与水和自然的关系;出现在云上(《2005.8.15》)以表明生命环境的可疑。有时,艺术家只想歌颂生命,他就把那个可能会被理解为纯洁与干净的婴儿放在金光闪闪的光环前面(《2005.5.1》);有时,他想表现即便是婴儿也会遭遇命运的不测(《2005.6.4》)。事实上,婴儿的造型与之前的“光头”容易发生关系,而涉及到的问题却是有所不同的。那些没有表现出“玩世”与“泼皮”的作品不过是体现了艺术家在这个时期全新的心境:自由、开放与悲悯。

在利用婴儿的象征性上,方力钧与张晓刚有相似之处,他们都同意:生命的诞生就是问题。可是,方力钧更愿意强调生命在一般环境中的特征,他要让表情说话;而张晓刚迷恋婴儿环境的戏剧性,那些没有具体来源的光构成了对生命的具体威胁。一开始,生命的原始冲动可以诱导自己面对自己的真实状态,这是“泼皮”产生的原因,可是,当真实的生命可以反省自身的时候,更为抽象的呵护之心就会浮现出来。鲜花既是记忆的产物,也是内心对生命的真实期许;婴儿既是幸福的结果,也是问题的开始,没有什么生命不是矛盾的产物,即便昆虫,也是生命的有价值的象征。在2007年11月的个人展览中,方力钧的作品中出现了大量不同类别的昆虫与禽兽,艺术家想说的是,这个世界不就是这样:我们很难说清楚不同的生命之间究竟孰重孰轻;当作为人类象征的婴儿驾驭着蝙蝠在空中翱翔的时候,没有人能够说清楚他们之间的利害关系。另一件作品表现的是以并不明亮的太阳作背景,拥挤成一团的儿童漂浮在大海上,他们究竟要去哪里已经不是问题的重点,四周出现的昆虫与生物对他们的命运正在构成威胁。他们的表情似乎焦虑、惊恐,但也没有紧张到不能自持的程度。如果我们观看仔细,还能够看到有飞向他们的小天使,那是吉祥的预兆,可是,各种各样的昆虫与白鹤飞翔的动态非常相似,这表明了艺术家对生命价值的判断没有坚持唯一性的标准。文明史里有很多关于通过牺牲来认同别的生命的故事,那就是说,任何悲苦与不幸都是相对的,并且是可以转化的。在这次展览上,方力钧使用了绘画、雕塑、装置等多种方式来呈现他自由而开放的想法。

从一开始,方力钧是那种从生活方式中自然导出艺术方式的艺术家,他甚至根本就反对将艺术视为生活的核心和孤立的东西,正如他自己说的:“你有什么样的生活就导致你有什么样的艺术。要不然你相反的话,先把艺术的事定了,再决定生活,这也有点不靠谱。”正是延着这样的逻辑,方力钧不同意对艺术有任何规定性,艺术不是具体的形式,不是什么神圣的观念,艺术几乎仅仅是一种可能性及其表现:

艺术的事,它没办法被规定。它的魅力就是你想描述它,你想把它摁住是不可能的。艺术本身它不是一件事。就好像一把锤子,这锤子不是一件事,它有各种各样的用途,有的人靠锤子谋生的,有的人靠锤子杀人的,有的人呢靠锤子保护别人的,它只是这种可能。15

与人们过去对艺术家的动机与神话的理解不同,方力钧彻底消除了对艺术家甚至艺术本身的崇高性与神圣性,他将艺术与艺术问题完全放在了“众生平等”的水平上:

有的人做艺术家就是为了钱,爱钱才做艺术家的,也不等于他不是个伟大的艺术家;有的艺术家可能就是好色,他才做艺术家的,不一定他就不是个伟大的艺术家。比如梵高,你看梵高日记里面,他不就是想过一个正常人的生活么,想找个满身是疮的妓女生个孩子,人家都不愿意和他生,也并不说明他不是个伟大的艺术家。16

这样的看法来自一种人生观和世界观,如果语言能够在人与人之间进行很好的沟通的话,我们不妨可以使用“有限”与“无限”这样的词语来表明涉及艺术的看法。我们经常使用“有限”与“无限”这样的词句,方力钧在一个及其通俗的层面上通过这样的词汇告诉我们:

我们一切的一切就在于我们自己的生命和空间都太小,面对一个我们无法控制和无法全盘理解的世界心里面太恐惧,我们老想把这个世界圈得比我们自己小,我们用各种各样的办法,这个世界比我小了,这个世界是一盘瓜籽,那就好办了,那我就放心了,我就安全了。

可是,在涉及到如何看待不同的艺术家在不同的观察者的眼中也许会有不同的结论时,方力钧强调了被认为是次要的、被忽略的对象在另一个层面和角度上的重要性:

人最最简单的悲哀和有限,就是你的生命和范围的有限性。你必须在有限的生命和可行的范围内做出一些事情来。像你说的这些丢了的人,他可能放在精神病院里面是研究重点,他也可能放在医院里面是个重点,你的课题如果是做这个必须被历史遗忘的人的个案里面他也可能是个重点。你的角度你要干什么是必须清楚的。

这个看法意味着,每个人都有自己的出发点,并且没有什么理由可以将这样的出发点看成是不重要的和不必要的。这样的看法与艺术家当初从事艺术,消解形而上观念的出发点是一致的。重要的是通过训练获得自由,这本身就是意义。的确,方力钧关于“自由”的看法与他的其他思想是紧密相关的。尽管他让人们最早知道的艺术就是对个人性和自我给予特别强调的结果,但是,他不认为存在一个绝对的自我:

我们现在说自我,我认为自我是扯淡的。物理上的你不是你自愿出来的,你没有这个要求,而是别人强加给你的;精神上的你也不是你天生就有的,而是生下来之后才有的。咱们要不要做一个试验,把这孩子如果放到以色列养,他长大以后恨死巴勒斯坦人,如果放到巴勒斯坦养,他以后恨死犹太人。所以说精神也不是你的,所以说这个自我完全是扯淡的勾当。不过,尽管你没有自我,你也绝对不能够否认自我。说欲望是无限的、世界是无限的,你再能耐可也不能追求无限,否则你就变得连沙子都不如,你现在一百多斤往四面八方一去的话就聚不拢个了。八十年代我们还不懂事呢,欲望就四面八方的产生了,我只能追逐四面八方,结果可能就什么都不是了。我还没有这定力呢。所以回到89年,也正好是我们这年龄,那个时间段的运气,你把你所有的内容、精神气、力量找到一个具体的目标,然后去做工作了。它比起刚才说到的那些反倒是容易多了。所谓的自由是根本就不成立的,我觉得如果找到一个目标的话有可能更自由。为什么呢?我可以从旁边进攻、从前面进攻,我可以捉摸上面、捉摸下边,也可以微笑的、很气愤地上去,我也可以假装跟它没关系,但是我的目标只有一个,这时候我反倒是自由的。因为从方法上我是自由的。如果我要是面对一百个这样的力量的时候,我要防备这一百个,我只防备这一百个就完了,我已经没有自由了。不要说我还要上面琢磨一下、下面琢磨一下,不可能了,力量已经达不到了。所以我们的角度和立场决定了对这个事情、这个形势的判断。17

正是因为自由的有限性,方力钧清楚,可以通过训练来获得相对更宽广的自由,他将没有经过训练的自由称之为“不可控的自由”,这样的自由将不会导致艺术的真正产生,甚至导致“你变成疯子”,“像泼水一样,水出了容器就自由了,但是收不回来了”。另外一个自由是可控的自由。“可控的自由一定是可以练就的。所以我们在谈到创作背景的时候,我们八十年代是自由的。对于可控的人,有控制能力的人它是自由的。对于没有控制能力的人,它就找不着地或者是汪洋大海,你一下去就没了。到了89年、90年的时候,对于可控的自由一样是成立的,一样是存在的。对于不可控的,这个就是监狱。就好像钢筋、混凝土被注到砖石结构里一样,你没有一点这种可能性了。所以我觉得离开人来谈自由不成立。但只要你提到人的话,对自由就只有这两种可能性。就是要训练。”18 无论如何,我们不能说我们前方的问题不是问题,可是我们可以通过训练来躲避与转化问题。经过了很多年的训练,方力钧表现出从对具体的个人状态的记录到对人的存在的更广阔的理解。从这个角度上讲,方力钧理解了水的重要性,他在领悟与体验中知道了相对性在什么样的条件下是合理的,而在什么样的环境中可能是没有意义的。他理解了个人生命的有限性,这样,他才可能去尽可能地理解涉及无限的问题。在写实主义的路线上,没有什么方法比方力钧来自广告实践的技法更简单的了:平涂、单色、简单的转折和轮廓线,可是,也很少有其他方法获得了方力钧的艺术那样的复杂性:对立的、不能单一解释的、也不是二者选其一的,或者说:不是善的,也不是恶的,不是丑的,也不是美的。方力钧通过他的艺术才能,确定了需要不断解读的关系,而他认为,当艺术家的工作导致了一种可以无限延伸的关系事实时,他的艺术便达到了一种境界。这样的看法让我们联想到古人的思想,例如“上善若水”这样的简洁的表述,我们很难对这样的文字作界限清晰的解读,并且,中国的古人都是这样看问题的,对世间和生命是不用饶舌的方式来理解的。与很多关于艺术的理解不同,方力钧没有将艺术看成是与其他生活截然不同的东西,在他看来,每个人如果愿意,他都可以使自己的生活与工作成为艺术——如果一定要用这样的词的话。早年,方力钧是“玩世现实主义”的代表,他以经典的图式将历史的问题定格,以便人们可以找到历史的形象象征;以后,他打开了用文字构成的思想藩篱,向人们提示了关于生命的道理:没有什么生命是高人一等的,但也没有什么生命是随随便便的。至于艺术,她的功能就是打开生命的可能性。

虽然“民主”、“平等”这样的概念模糊不堪,但是,作为一个特定历史时期中的常识,人们还是知道它们的基本含义。可是,这不意味着众生的能力与智商的是均等的,人类的有效存在正是种种不均衡性推动的结果,而导致这种不均衡性的原因之一就是深藏与人的灵魂结构中的那些能力以及文明社会赋予艺术家的权力,方力钧同样提醒了这样的问题,他强调说,作为艺术家应该具备的素质与敏感性:

艺术家有一个天生的优势:艺术家是人类社会里面唯一的、可以特别嚣张的、宣誓自己的生命不可以被代替的一伙人,在这个行业里,在人类这个集体里还有其他的行业类似于,但是都没有艺术家嚣张。所以从这点来说,艺术家的成功是带着先天优势的。但是很多人从事这个行业,却没有发现自己所具有的先天优势,所以他就不成功了。所有那些不怎么成功的艺术家,他肯定是没有发现这个先天优势的。我们很多的艺术家,别人觉得比较傻、比较弱智的都成功了,因为他发现这个优势了。他可以宣誓:我是唯一的,我是不可以被代替的。因为人性是共通的,无论你怎么叫嚣你是不可以被代替的,还是能够理解你的。所以通过这样的一种结合、一种关系,傻子在艺术圈里面也能够成功,唯一不能够成功的,就是没有意识到他自己先天优势的人。当然,有些人在理论上没有认识到,但是他这样做了,蒙着做了,他也成功了。其实艺术家这个职务变成很能讨好人类的职务了,你们平时都不敢说,在上司面前、在体制面前或者在各种关系或者因为教育的问题或者伦理宗教什么的一切的问题,你不敢把你心里想的这些东西发泄出来;或者说因为所有这些约束,你根本就不敢像我一样是唯一的。你只能像在此刻的我是这六十多亿人口里面的一个。所以艺术家所有的行为,所有说出来的话,几乎都代表了全人类的渴望。在这个平台上面,谁说出来的这些话代表更深刻的更急切的这种愿望,谁就成功了。19

方力钧在当代艺术史的重要性,可以从艺术家所陈述的逻辑中得到理解,或者说,我们可以从艺术家的看法中感受到他是怎样走出自己道路的。

2008年2月29日星期五

1 转引自汪继芳:《20世纪最后的浪漫——北京自由艺术家生活实录》北方文艺出版社。

2 皮力:“和方力钧的谈话”。

3 户口本上是富农。但在那个阶级斗争的发年月,没有申辩的可能。

4 陈红云:“方力钧的自由心灵之路”。

5 出自舒可文主编:《线索》。

6 栗宪庭的《无聊感和“文革”后的第三代艺术家》一文初稿,写于1991年3月。

7 栗宪庭的《无聊感和“文革”后的第三代艺术家》,1991年8月稿。

8 邱志杰:《立场》。

9 皮力:“和方力钧的谈话”。

10 栗宪庭:“方力钧创造的‘光头泼皮’”(2000年)。

11 尹吉男主持:“方力钧口述”(1998年12月)。

12 尹吉男主持:“方力钧口述”(1998年12月)。

13 尹吉男主持:“方力钧口述”(1998年12月)。

14 栗宪庭:“与方力钧对话”。

15 吕澎:“脱口艺术问题”(2008年2月)。

16 吕澎:“脱口艺术问题”(2008年2月)。

17 吕澎:“脱口艺术问题”(2008年2月)。

18 吕澎:“脱口艺术问题”(2008年2月)。

19 吕澎:“脱口艺术问题”(2008年2月)。

Questions like “How does a man react to this world?” “How to comment on a man’s reaction to this world?” are meaningless except for psychological tests. Who, when, what happens or what kind of reaction? Normally these discussion and judgment are reached through certain rule or commonly shared criteria of goodness. Before we clarify these questions, how can we be so confident to say that the certain rule of criteria of goodness we chose is unshakable?

“We are cheated repeatedly. We’d rather be called as the lost, the ennui, the dangerous, and the bewildered than the cheated. Don’t ever think of using the old way to preach us. Any creed will be stamped with ten thousand of questions, then get denied and thrown to the dustheap.

This is what Fang said after 1989.

At that time, the man was approaching 30, living poorly in the village of Yuanmingyuan. He completed his first series that filled with his own characteristic. According to him, “those isolated or unsmooth things were totally washed away” and he had “an unrestrained feeling.” Literally it seems that the artist obtained his freedom. But without the help of context, it is difficult for us to link “cheated” “lost” “ennui” and “dangerous” with words like “smooth” and “unrestrained.” If we try to understand these unmannerly words through the background of the 80s in China that advocated the liberation of the spiritual, we could hardly make any comment on the artist’s spiritual condition. As Nietsche’s “God is dead” reminded the Chinese contemporary artists that any doubt towards any fixed principal or value were legal. It seems that Fang’s angered emotion was different from those descriptions in his cynical image in the early 90s. He firmly expressed his unbelief towards everything. What was the reason behind?

At the beginning, all man’s heart is akin to a piece of empty paper, even though it is loaded with some inherited factors. If the “empty heart” is put under certain environment, the changing environment will influence the “colors” presented by the heart. Many years later, Fang says “There doesn’t exist the abstract inborn nature in human beings, the inborn nature is only acquired through one’s experience in society.”

Born in the end of 1963, the birth of this clean soul (later appears in his tableau in the form of newborn baby) coincided with the meeting hosted by Chairman Mao in Hangzhou. The result of the meeting brought out a political document that emphasized the critical factor to decide the success of socialism was class struggle. Fang’s grandfather was a landlord, an identity that he could never had the legal right after 1949. Under the severe backdrop of class struggle, the identity of landlord became an attacking target. The Chinese Communist Party strategically made use of different classes in different historical periods. But under the system that only the top leader could arbitrarily make regulations and policies for his country and his people, different opinions and conflicts in the Communist Party were revealed through different political and social life. The identity of a landlord was not protected, only the politics demanded. As a little kid, Fang was not able to react to this world with a clear view. But he definitely couldn’t escape the “air of politics”. The violence and attack under the name of “revolution” initiated from the “cultural revolution” in 1966 must have left some traces in the tender heart of this child, even though he was unable to see those social issues with a rational view. Now it is hard for us to imagine what the little boy’s feelings when he heard the roar “Flatten the Landlord” by his neighbors. But one thing is for sure, those shouts and the insulting words written on the backyard gave a strong hurt in his heart. He was six years old in 1969. Later the artist recalls that he joined an attack meeting, but when he shouted with the other “Hang up the old guy”, he found that the old guy was just his grandfather. Fang’s experience is not unique in the politic turmoil starting from 1949. But how to judge between the basic instinct of goodness aroused from kinship and the negative feelings given from the surroundings? Revolution or goodness, which one is more needed by the collective? Or we have to accept that the goodness never exists? Fang grows up in an environment filled with revolution and violence. When he was able to write some words, he gradually knew how to use these words to please his teachers. For example, he described the thick smoke hovering over the chimney as colorful clouds in the sky, since a socialistic country demanded acclaim and extol. Fang even has memories “Before the open door policy, I had lived in hatred and struggle. Because of the unfairness of my origin, I had to sometimes tolerate and fake as child. For example, when Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou died in 1976,we all went to the mourning hall. My father hinted me that I should cry, and I knew I should. But at that time, I had no rush for cry, while later I really cried a lot. Everyone came to comfort me and my teacher praised me. Then I knew if I faked sometimes, I would receive praise from the others. This was the result of education when I was still a boy. Usually what you were taught went to the opposite direction for what you thought was right. Now I recall that I became a two-faced character since then. This is not a question whether you are willing or not, as the pressures from the environment weigh a lot on you even when you were little.” At that time, the little heart learnt the trick of switching between the good and the evil without the understanding of how to fix those abstract principles he interpreted in a certain society.

In fact, Fang’s personal experience is not a big deal, and what he has gone through is only a part of the ordinary life that many Chinese ordinary people have gone through. During the bygone days with the theme of class struggle, no one was safe and reliable. There was no moral criteria in protecting oneself, as there existed no moral criteria, or in other words, the moral criteria itself was totally replaced by the standard of class struggle.

In order to avoid any mishap, Fang accepted his father’s suggestion and started to learn painting. The learning at the fine art training classes aroused his love for painting in middle school, giving the boy the confidence in his later artistic path.

In 1980, Fang entered the Hebei Light Industry College where he could learn art under a professional surrounding. Most important of all, there emerged a new context that year. Early in June 1979, “Fine Art of the World” was launched and published the article written by Shao Dazhen on Western modern art style, but previously any Western modern style was severely prohibited in China. The magazine also published the article written by Wu Guanzhong on the beauty of form, while previously such subject was categorized as bourgeois thing that were prohibited and attacked. Later another magazine published a cartoon series featuring the accusation of the political turmoil during the “cultural revolution”, implying that people could freely release their resistance and dissatisfaction or lament their fate in public. Soon “Fine Art of the World” immediately organized a discussion on this cartoon series. People started to thoughtfully question and understand the notion of “truth,” giving their warm concern on the abstract subject of humanity. In September 1979, Yuan Yunsheng’s mural painting titled “Water-splashing Festival” on the capital’s international airport amazed many viewers and received a great controversy. In particular, the parade of the first exhibition titled “Star Movement Exhibition” at the national art museum shocked many people, as sensitive words like “democracy” and “freedom” appeared in the parade. But all these had nothing to do with Fang in the city of Han Dan, even such historical backdrop provided him and his peers a fresh social reality that they would soon experience. After his entrance to the college, he was able to learn about the prevailing Western modern art in China. In March, the awarding of the national art exhibition in celebration with the 30th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China was finished. Some canvas filled with sentimental and blue feelings was recognized in a government-organized exhibition. The fascism in “cultural revolution” was attacked in the public. When absorbing all kind of knowledge, Fang found a new attitude towards history through these “trauma art.” Although these artworks created by Luo Zhongli, He Duolin, Chen Conglin, Zhang Xiaogang, Zhou Chunya didn’t solve the problem of modern language, yet what reflected by these pieces were powerful and genuine. Even as a child, Fang expressed his intellectual sensitivity so that he could experience the charisma of realism through these artworks of “trauma and local art.” Such impression and experience overlapped with those colors and symbols reflected in his heart. Perhaps at the beginning, everything started subconsciously, but gradually his inner world knitted up with his experience from his personal life, from society and art became complicated.

There is an important sketching experience in Fang’s life. In 1982, he went to She County in Tai Hang Mountain with his friends. The landscapes there were reminiscent of those “local art.” They were pure and natural, but not rich in resources. Later his “Nostalgia” and “Untitled” are considered to be connected with the environment and people there. His watercolor series “Nostalgia” undoubtedly was the outcome influenced by the popular style at that time, but the simplicity of the natural environment was actually an important reason to touch the artist’s heart. Perhaps it is not because that local style has certain charisma, but because the actual countryside scene that satisfies those uncontaminated part in one’s heart. In the arrangement of “Nostalgia II”, warm and even sentimental feelings revealed the actual yearning of a graduate student from a technical secondary school who had already learnt how to tell lies. The series were selected for the 6th National Art Exhibition, adding great confidence to Fang, at least he experienced the power of truthfulness. While the connection between the scree and the baldhead image is hidden that needs time to unfold.

A large reading on Western books was a common trait for young people of the 1980s. In Fang’s memory, he didn’t pay attention on those post-modernism ideas, let alone the obscure notion of the pioneers of modernism. What moved him were those masterpieces with enlightenments

“I want to talk about those books that greatly influenced me. Emiley’s “Withering Heights”, Rosseau’s “Confession”, Hugo’s “Year of 93”, Irving Stone’s “The Lust for Life” and Duncan’s autobiography. I encountered them when I needed them the most. The three sisters in “Withering Heights” all lived in the countryside in UK with a fairly isolated life style. Their imagination and overwhelming experience all came directly from their heart, which made me realize that life was to be “savored” through one’s heart. A fool is a fool, even when a series of different overwhelming incidents happens in his life, they leave no trace in heart. This is not life. In “Confession,” Rosseau wrote that he adopted a girl with his friends when they were young. Their aim was to use that girl as a sex toy later. However with the flow of time, they nurtured the real father-and-daughter relationship. Finally Rosseau didn’t treat the girl as he planned. Rosseau didn’t hide himself, but told all these nasty things through a naked heart. Thus he became candid and transparent. That made me thoroughly realize humanity, a man’s respect and a man’s right. Those free artistic ideals in Duncan’s autobiography with a simple expression immediately caught me. Even today when water appears under my brushstrokes, I always doubt if it is related with the description of a child dancing under the azure sky in her book. When I am thinking about each question, all these books would appear and impact my soul with their amazing power.”

If we compare all these inner emotions with Fang’s cynical feelings, we could see that there must be something deeply hurt him. The intellectuality nurtured in the mankind’s civilization is eternal. Such eternity echoes with the inborn moral sense of a man. Most important of all, one unique system could separate such universal moral sense or good will from a man’s own requirement. The separation merely serves for its own purpose or an abstract ideal. But when such ideal is set as all men’s common will, then eternity, moral sense and good are gone. When Fang had the opportunity to read these words calling the freedom from his heart, what he perceived was overwhelming. It not only strengthened his knowledge, but also powerfully confirmed the existing purity in his heart. Because of these gains, there was not need to understand those obscure philosophy and notions for the artist. Naturally there is no evident material recording Fang’s interest towards the abstract philosophical books, even though such interest prevailed among artists who were born in the 1950s at that time.

The extreme fighting character is a common trait for those who cannot protect themselves via power or other social resources. In his childhood, Fang was unable or courageous enough to drive away the shouting “Landlord Fang,” he silently witnessed everything and released all his inner pains through playing. He pretended crying to obtain sympathy and recognition from the others, while ironically such pretence was almost hard to discern. When he entered college, the regulation and rules of the college hindered the freedom in his heart, but he can’t go against these rules. For example, one of the rules stipulated that the sideburns of all boys shouldn’t be longer than their ears. As a result, he and his classmates gave a close shave. What he tried to manifest was that “I could make it more thoroughly and cleanly than you demanded.” This is a form of rebellion, a rebellion that sacrifices one’s freedom or re-gain one’s freedom through self-denying. It is one of the ways to deal or understand the difficulties in one’s life. Such method carved deeply in Fang’s heart with an ineffaceable memory and the potential explosion of emotions. For him, the explosion of emotions and memory are simultaneous. “From then on, the baldhead image has a kind of rebellious or cynical flavor in my sub-consciousness. The sub-consciousness is the resource of memory while rebellion and cynicism are forms of explosion.”

“Nostalgia” was created when he was working in an advertising company in Han Dan. In 1984, he traveled to Nanjing, Shanghai, Guangzhou to see the 6th National Art Exhibition. Soon, he quit his job at the advertising company. In 1985, Fang studied at the print department of the National Central Academy of Fine Art. The strict rules at the university plus the new wave art movement outside the campus gave him the freedom to study and live. He and his classmates were free to choose their reading materials, study method and life style. During his campus days, Fang was able to indulge himself in different resources, pondering, selecting and practicing all the possibilities. It was not until 1988 that Fang painted his earliest baldhead images on sketches. We could see that Fang’s sketches had nothing to do with the Russian style. The round and smooth painting style greatly differs with the blocks, planes and structure emphasized by the academy.

In February 1989, Fang sent his sketches to the Chinese Contemporary Art Exhibition at the National Art Museum, but they hardly received any special attention from the visitors. The gathering of modernism, perhaps a little late, was too chaotic and noisy, the dazzling artworks and the shocking gunshots almost left no time for people to appreciate those paintings on the wall. Most important of all, because of the political campaign of “anti--bourgeois freedom” that started from 1987, the driving power of modernism began to fade. The question of essentialism was exposed, yet the chaotic social aura of 1988 blurred the issue. In fact, post-modernism and the words about abandoning essentialism appeared. Wang Guangyi’s “Mao”, Wu Shanzhuan’s “Selling Shrimps”, Li Shan’s “Footbath”, Zhang Nian’s “Incubation” plus blackmailing letter, condoms, and the purposely-arranged gunshots by Xiao Lu and Tang Song, all together formed the problems that the critics were concerned. Fang’s baldhead images surely had nothing to do with the metaphysical ideas of Ding Fang, Shu Qun and Mao Xuhui. He is not a member of the 85 New Wave Art Movement. But it seemed that he was prepared to joint the parade. Although he showed his baldhead filled with local flavor to those contemporary art critics, yet his artworks were not focused. Seemingly Fang didn’t have confidence for himself. He said, “It was unwitting for me to paint the baldhead images, and the backdrop is imagined. The repetition of these images is a kind of practice and contained something. But I didn’t have alternatives. So I wasn’t confident to exert them.” One thing was for sure, whether baldhead will have a striking influence in Chinese contemporary history or not, Fang at that time didn’t ever think that his baldhead had any impact in art.

The June 4th Event shocked the whole world. How to confront something hard to escape was stretched in front of him. In his subconsciousness, Fang already had his experience of encountering overwhelming violence. Now, he witnessed the failure of direct rivalry. Whether such rivalry was theoretically effective or not at that time, Fang naturally chose to concede or shy away. He felt the feeble power of an individual, and the only way to be rescued was through self-redemption. It was not a time to discuss who was right or wrong. In fact, it was hard to clarify the issue, as the question was so big and beyond the capacity of personal power. He knew by instinct that he should care about himself by himself. At that time, he was busy planning and working for his own surviving, and he had no choice. In July, he moved to a studio between Yuanmingyuan and the Summer Palace. The life there was cheap, and he could fully engage himself in painting. But the next year he was forced to move out when he finished his early sketches and oil paintings. He moved to the courtyard of the peasants. During that year, he and his friends wracked their brains to feed themselves by selling postcards or painting military teaching map. In summer, Fang found a studio in Yuanmingyuan where his “First Series” was completed.

Again Fang chose to “step aside” from the bottom of his heart. The reason for his “unrestrained feelings” after the summer of 1989 was because the ineffective rivalry inspired the power from his heart to head-on. In his early series, Fang was guided by instinct by the subjects that he painted including the simple landscapes and peasants. At that time, he even painted vividly the teeth of the peasants, repeatedly emphasizing the simplicity the honesty blended with obliquity and subtlety. But he still thought that he didn’t make clear of what he was trying to say, even though these traits echoed with his nature. By instinct, he shied away from anger, depression and redemption. Sometimes he put his figures in difference distance, observing the bizarre scene in the bloomy backdrop. But seemingly that was not his purpose. From 1989 to 1990, there appeared a girl in glasses both in his sketches and painting, perhaps this was the recording of his personal life, as we often could clearly see himself in his artworks. In the sketch, the artist increased the volume of the girl, which might be the outcome of a strong exaggerated perspective view, and he quietly sat besides the girl. But we could still find the repeated images of those peasants in Mount Taihang who followed closely after the artist. Surely, we could say that the artist retained his nostalgia in his arrangement. But he emphasized the baldhead image in his sketches, as baldhead often renders a strong impression to the viewers. He also conjured up a bit ambiguous touch that might adjust the viewers’ feelings, driving them away from the oppressed emotion normally prevailed in the modernism artworks. He repeated the portrait of one man, emphasizing the particular personal feeling through such repetition. It was not until “Sketch Five” that Fang put his character under a more broadened backdrop. The spacious Tian’anmen Square and the recent boundless space perhaps suggested that Fang thoroughly broke away from the stone all of Mount Taihang or the concrete environment. The opening of his heart enabled him to obtain the “unrestrained” feelings. He combined with his rebellious experience, the image of Tai Hang Mountain peasant and his distance of modernism. He started to cut those redundant details in his paintings and re-planned a fresh new image. Soon, Fang abstracted his future direction in “Canvas Four.” According to him, the importance of this art piece lies in his selection of the baldhead as a new start. Immediately after the experiment of a series of black-and-white canvas, he solved the technique problem of oil paint. Then he began his representative “Series.”

In march 1991, Critics Li Xianting started to conclude Liu Xiaodong, Fang Lijun, Liu Wei, Wang Jingsong, Song Yonghong and some artists into different categories. Li started to use the word of cynical realism. In 1992, the exhibition curated by Francesca Dal Lago and Hans van Dijk exposed Fang’s representative artworks to the public. Critics began to decipher the new artistic phenomenon. In the album of this exhibition, Li described Fang’s artwork as follows:

“Fang chooses those accidental, mediocre, and boring fragments in life as the first layer in his art. Those baldhead images form the core in his art. Thirdly, he puts these unromantic borings images in a poetic environment such as the azure sky, the snowy cloud and the vast sea, rendering an absurd ambivalence. He graduated from the print department at the National Central Academy of Fine Art in 1988. He has a fairly solid base in sketching. Canvas is not his specialty, yet he finds a technique echoing with his mood and feel, similar to the advertising painting technique focusing on neutrality with no intention to express, which on the contrary permeates an indifferent aura on his canvas. The hues that he adopts are also not traditional. Big blocks of soft pink colors form a contrast with other hues, rendering something distant away from life while at the same time emphasizing an absurd visual effect.

He started an art journey titled “cynical realism” through “Series” from 1990 to 1991. The tiresome gape and the indifferent gaze of the characters in his paintings are reminiscent of Li’s analyze.

“All sensitive artists are nearly facing one common living dilemma: the realty is often fused with the meaning of different cultures and values. The overwhelming system dominates their surviving surroundings. But when dealing with the dilemma, the representatives of cynical realism greatly differ from the previous two generations. They believe neither the dominating system nor the illusionary efforts in building up a new meaningful system through rivalry. They practically and faithfully face their own helplessness, and only self-redemption could save them. Ennui is the most powerful way to offset the meaningful shackles around them. When reality couldn’t provide them a new spiritual background, meaningless meaning becomes their most helpless method in pursuing a new meaning in life and art, the best method for self-redemption.

What Li Xianting suggested is a real historical scenario. As the witness and recorder of such historical scenario, Fang, through the recording of his own spiritual condition and expression, describes vividly the spiritual condition of the typical Chinese locals, in particular the Beijing locals of this social period. The emotions wafted over Fang’s artworks are reminiscent of Wang Shuo’s novels themed “Don’t treat me as a human being.” When people started to understand and accept Fang’s art, they also started to understand Fang’s saying “I don’t want to be fooled again.”

Confronting this helpless world, Fang adopts his own strategy. He sees the world in an opposite way: he becomes the world. Like artist Qiu Zhijie said in 1993 “Each cage shuts the outside world outside.” Likewise, at the beginning, artists by instinct have to face their own problems. Fang keeps the baldhead image in life while paints baldhead to express non-individuality. Art mirrors life and life becomes part of art. Fang’s later works alter under such way. When he cuts all the details, he thinks that he could further realize his ideas. Many years later, he explained why he repeated the baldhead image.