由上海艺博画廊与丹麦艺术中心联合策划的展览“CHINAMANIA”于2009年6月27日-9月27日在丹麦阿肯当代美术馆举行。

"CHINAMANIA" curated by Shanghai Yibo Gallery & Beijing dARTex Gallery showed at Arken Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen, Danmark. Jun.27 - Jul. 27, 2009

NEW PAINTING IN CHINA

LOTTE PHILIPSEN

At first glance, the works in the CHINAMANIA exhibition seem easily accessible. They are executed in a style sufficiently realistic for us to recognize the motifs. Most of them are colourful and of considerable size, hence they attract attention. Basically, it is just a matter of starting to look. Whereas the process of experiencing the concrete works is thus a task for the individual guest at the exhibition, this text aims to position the works of the exhibition as a part of the new painting in China in recent years, and to consider this new painting in the broader context of art history. Since each work of art is unique and has its very own formal expression, in principle it is not possible to consider the works of the exhibition as one homogeneous unit. Nevertheless, if we try to comprehend this new Chinese painting as a phenomenon, we need to consider how it is “new”, how it is “Chinese”, and how it is related to the traditions of the art form of “painting” in China and the West – and, not least, how these three aspects are in evidence in the works in question. Is it the motifs that are new, the style that is Chinese, or is it the way in which the artists respond to the Chinese and Western traditions of art? In order for us to answer such questions, it is fruitful to begin by asking the fundamental question: what do we mean by “the medium of painting”?

Technically, painting can be executed in many different ways. Facial painting, water colour on paper, Michelangelo’s fresco in the Sistine Chapel, and airbrush decoration on a motorbike are all different kinds of painting, but when we speak of painting in modern and contemporary art, we automatically think of oil paint or acrylic paint on a stretched canvas. At least, this is the case in Western cultures, where this type of painting is also termed “easel painting”, because the canvas (or earlier, the wood panel) is supported by an easel during the painting process. In Europe, this has been the dominant form of painting as art since the 16th century, when the existence of art as independent from the church, the state, and courtly assignments gradually emerged, and eventually resulted in a bourgeois understanding of art as autonomous and original, in the sense that a work of art is unique <1>. It is this concept of art, among other things, that lies at the root of Western art museums, where the work of art is framed in a particular discourse of aesthetics, and in which the presence of the original work of art is considered pivotal, rendering the mobile easel painting extremely suitable as an object for exhibition in the art museum <2>.

In China, however, this type of painting is of more recent date. Not until the beginning of the 20th century did Chinese artists start to use oil paint, inspired, among other things, by the strong, mutually influential relationships between the Sino-Japanese and the Parisian art milieus at that time <3>. Up to that point, the tradition of painting with ink on rice paper or silk (often combined with literary calligraphy) was the common type of painting in China. This tradition continued its dominance, even after oil painting made its entry among Chinese artists. Accordingly, the art history term, “Chinese painting”, does not cover easel painting from China – it instead covers the “ink on paper” tradition. The progressive Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing – from which Fang Lijun, Qi Zhilong, Mao Yan, and Liu Ye graduated – thus has a “School of Chinese Painting”, as well as a department of “Oil Painting”, which is the one that teaches what we know as painting in the European tradition. Whereas the works in the CHINAMANIA exhibition are not related to Chinese ink painting, they can be ascribed to the Chinese tradition of oil painting stemming from the beginning of the 20th century.

In addition to these two different technical traditions of painting that exist side by side in China today, a tradition of ideological pictures has been influential, since Socialist Realism (from the Soviet Union) became popular after the takeover by the Communist Party in 1949. Technically, Socialist Realism is often oil painting, but since the purpose of Socialist Realism – as opposed to that of traditional European easel painting – was to propagate the politics of the government among as large a portion of the population as possible, the material’s originality and the uniqueness of the work were not the focus. The painting’s motif – its image – and its ability to communicate a socialist message were paramount, and therefore these paintings often functioned as sources of posters that were printed in large numbers of editions, and widely distributed <4>.

Two different painting traditions constitute the historical foundations of the type of contemporary painting that we encounter in this exhibition: Easel painting, which is connected to an autonomous concept of art stemming from Europe, and Socialist Realism, which, in contrast, is based on a utilitarian concept of art, where art must serve the political interests of the government <5>. However, for us to be able to position the contemporary paintings of this exhibition in relation to these traditions, we need to consider yet another significant art form, that being photography, the tradition of which appears more focused in China than it does in Europe. This is meant quite literally, since photography’s ability to reproduce a given motif clearly has been highly valued in China, whereas its potential to create pictorial or decorative images does not play any significant role in the history of Chinese photography. Hence, in the Western sense of the term, China does not have a modernist discourse of photography that has explored the ability of photography to create or develop, for example, poetic effects caused by the interplay of light and shadow, or pure visual drama through compositional cropping, in the way that Europe has. However, this is not tantamount to viewing photography in China as a strictly documentary medium. On the contrary, China has a strong tradition of staging the photographic motif in ways in which characters, objects, background scenery, and point of view come together in carefully and conceptually planned pictures, and today contemporary Chinese art photography generally has a razor-sharp focus, bright colours, and is characterized by imaginative digital manipulations <6>. It is because of this ability to stage their (imaginative) motifs, that contemporary photography and painting in China are closely related.

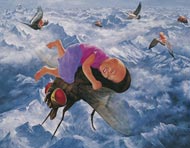

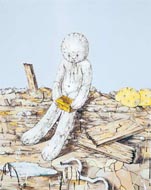

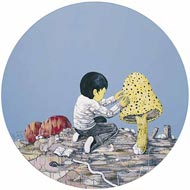

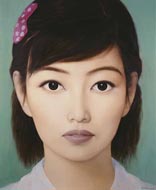

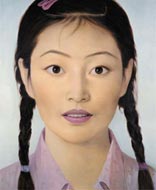

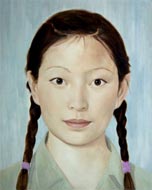

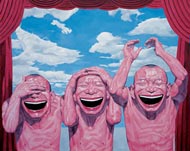

Now, how are the paintings of the exhibition positioned in this heterogeneous field? Regarding the subject matter, they are primarily figure paintings, in which one or more persons are seen in a relatively simple and empty environment: Li Jikai’s little child sits in a box in a deserted landscape, Yue Minjun’s grinning men act on an empty stage with the open sky as a backdrop, and Liu Ye’s portraits are seen on empty, coloured backgrounds, like the figures of Yang Shaobin. Even in cases in which the figures find themselves in more elaborate environments – as in Fang Lijun’s painting 2009. No. 5, which shows gigantic birds and insects with small children on their backs soaring over jagged, snow-clad mountains – the space refuses to incorporate the characters within a broader illusionistic, societal or social context.

To a large extent, it is possible to view the motif described above as a reaction to Socialist Realism painting, in which the preferred visual matrix was pathos-dominated, and involved dramatic story-telling. In Socialist Realism, motifs – for example, the masses celebrating the leader, the industrial worker determinedly tightening a bolt in the name of the common interest of the nation, or the peasant woman offering the soldier a meal – all constitute a narrative semantics aimed at placing the individual figure in the greater context (of meaning). As a result of its motif-related insistence on figure painting permeated by a sense of alienation and fragmentation, this new tendency in contemporary painting in China goes by the name of “cynical realism” <7>. Art critic Li Xianting believes that the art of cynical realism is to be comprehended as a sarcastic reaction to the political suppression of the Chinese people for thousands of years. The way of life of the young people expresses a no-future mentality – an indifferent and contemptuous attitude towards society <8>.

In particular, the figure painting of cynical realism is carried out in a colourful and linear style – evident in works by Liu Ye and Yue Minjun, for instance – that intentionally makes use of a simplified manner of expression, which renders the figures clear and simple, and which seems related to conceptual photography in Chinese contemporary art. This is also the case in works by Yang Shaobin and Wang Guangyi, but here, the style itself conveys additional motif-related elements through inspirations from the history of art. The works of both painters are characterized by compositions in the style of collages, in which various fragments are appropriated from different forms of picture making – such as photography, animation, and cartoons – and presented in new contexts.

In Yang Shaobin’s work, Untitled (2007), we see a number of different motifs on a flat, dark red background: A scene depicting an operating table is mixed with expressive and partly dissolving faces, and a twisted body crowned by a halo. In the lower right-hand corner is a pair of worn-out shoes, the original of which Vincent van Gogh painted in 1885, and which art historian Meyer Shapiro has interpreted as van Gogh’s metaphorical self-portrait <9>. In this case, it is not the placement of the painting’s fictive characters that seems alienating – instead, it is the very lack of a single coherent, motif-related syntax that estranges the viewer from the picture. The image does not submit itself to direct viewing or observation – instead, it shatters the dominant gaze of the viewer, and looks back, like the photographer in Yang’s painting, who confronts and captures us through his camera. In contrast to the flat and anonymous background, the twisted faces are painted with wild and expressive brushstrokes, indicating that the artist himself was deeply involved in the process. The very idea that the artist invests himself emotionally in a work of art originates in the Romantic theory of art, which flourished in Europe during the first part of the 19th century, but is very much alive and kicking today. According to the Romantic theory of art, the artist-subject possesses an exceptional sensibility, which connects him or her more closely to nature, to God, and, ultimately, to human existence as such; the artist is able to convey this exceptional sensibility through his works. Hence, even today, when conceptual work plays a significant role in contemporary art, great value is ascribed to concrete signs of the artist’s personal involvement in the process of the work’s creation – for instance, visible brushstrokes, or personal artefacts, like the shoes by Van Gogh <10>. By staging such disconnected fragments – signs of the expressive artist-subject – however, Yang, renders them empty, mere conceptual pictorial components. In other words, the references and the style point to a subject that turns out not to be present at all.

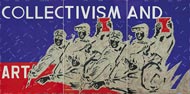

In Wang Guangyi’s picture, Collectivism and Art (2007), the painting’s style, too, attracts attention. Wang is known for juxtaposing commercial Western logos, for example those of Coca Cola and Gillette, and groups of figures from the Socialist Realism of the Cultural Revolution, as critical commentary on fundamentalist tendencies in the domain of capitalism, as well as communism. In this work, the group of figures is once again modelled on Socialist Realism, wherein everybody looks and points in the same direction, and in the back, two persons even wave copies of the little red book of Chairman Mao Zedong’s quotations. However, Wang has painted the group in a style that resembles woodcut technique, instead of painting. Consequently, the group appears graphical and hollow, and furthermore, the style undermines the oil painting’s status of uniqueness, since the technique of woodcut is characterized by reproducibility, and hence is well suited to the distribution of images to greater portions of the population. And, thanks to the fact that the technique of woodcut results in a linear and simple style, the motif is easily recognized by the viewer. Woodcut plays a special role in the visual culture of 20th century China, as an extremely popular medium for disseminating visual political propaganda – against Japan in the 1930s, and in various official campaigns, since 1949 <11>. By embedding the style of a woodcut in his painting, Wang thus refers to a visual tradition that was formerly widespread in China, and an additional appropriation of style is present in the painting’s English text – collectivism and art – which, on closer inspection, turns out to be written in an odd typography. Seemingly, the letters are lifted from different fonts, for example the A’s are in a different font than the L’s, which renders the visual whole of the text unstable, and contributes to the sense that the style of the painting obscures – or perhaps is transformed into – the motif. Thus, Wang’s painting not only deals with the Cultural Revolution and the use of art in the service of the common good, but also addresses visual communication as a phenomenon that is in an ongoing dialogue with a broader public sphere, in contrast to the concept of autonomous and original art, associated with easel painting, to which Wang’s painting itself belongs.

Some of the works in the exhibition seem in accordance with cynical realism in their motifs, whereas their poetic style deviates from it. This is the case with the works by Mao Yan and Wei Jia, for instance, which – despite the fact that their figures, too, are placed in pictorial vacuums – present a painterly and abstract style, which renders these paintings more expressive. Hence, these paintings seem to be stylistically in accord with the tradition of the Modern European concept of art that regards the work of art as the direct expression of the artist’s emotional state.

Consequently, most of the exhibition’s contemporary paintings subscribe to a specific Chinese pictorial context that manifests itself, not through the fact that the figures depicted look Chinese, or that the motifs contain symbols from the Cultural Revolution, but because the images created relate to a Chinese artistic context, when the works’ motifs resemble those of conceptual photography, and their styles create illusions of artistic techniques such as woodcut, and propaganda art. Although painting in oil or acrylic is no longer the exclusive preserve of Western artists, as this is a common and widespread technique internationally, many of the works in this exhibition use oil painting in ways that relate to a Chinese context. Does this mean that we should consider these works as particularly “Chinese” paintings? Preferably, not. Such a nationalistic understanding of the works would mean that we, as viewers without a specific Chinese background, would debar ourselves from contemplating and judging the works as pictures that give rise to several different layers of meaning, depending on the contexts in which the works are experienced and presented. Rather than viewing the works as transparent windows to Chinese culture, or as unique and valuable paintings on the museum walls, we may benefit from seeing them as thought provoking image-creations that are not finished, but are always evolving, because we, as the audience, extend them, and pull them in new directions.

<1> See Jean-Marie Schaeffer: Art of the Modern Age, Princeton University Press, 2000

<2> For the sacral dimension of the art museum, see Carol Duncan: “The Art Museum as Ritual” (1995) in Donald Preziosi (ed.): The Art of Art History, Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 473-485

<3> See Mayching Kao: “Reforms in Education and the Beginning of the Western-Style Painting Movement in China" and Kuiyi Shen: "The Lure of the West: Modern Chinese Oil Painting”, both in Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen (eds.): A Century in Crisis. Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China, Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1998, pp. 146-161 and 172-180

<4> For an elaboration of different kinds of painting in the Chinese propaganda art see Ralph Croizier: “Politics in Command, Chinese Art, 1949-1979” in Melissa Chiu and Zhang Shengtian (eds.): Art and China’s Revolution, Asia Society, 2008, pp. 57-73

<5> For an elaboration of the opposition between these two types of art, see Clement Greenberg: “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939) in Greenberg: Art and Culture – Critical Essays, Beacon Press, 1971, pp. 3-21 and for discussions of the relationship between the avant-garde art and politics in China, see Norman Bryson: “The Post-Ideological Avant-Garde” in Gao Minglu (ed.): Inside Out, New Chinese Art, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 51-58

<6> See, for instance, Wu Hung and Christopher Phillips: Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China, University of Chicago Press, 2004

<7> At the beginning of the 1990s, the art critic Li Xianting was the originator of the notion of “cynical realism” in his characterizations of the work of Fang Lijun, Yue Minjun, and Yang Shaobin, among others

<8> Li Xianting: “Chinesische Malerei der Gegenwart – Rezeption und Integration vielf?ltiger Traditionen” in Dieter Ronte and Walter Smerling (eds.): China! Zeitgen?ssische Malerei, Kunstmuseum Bonn and DuMont Buchverlag, 1996, pp. 176-183 and p. 179

<9> Meyer Shapiro: “The Still Life as a Personal Object – a Note on Heidegger and Van Gogh” (1968) in Meyer Shapiro: Theory and Philosophy of Art: Style, Artist, and Society, George Braziller, 1994, pp. 135-141. This interpretation has later been discussed in Jacques Derrida: The Truth in Painting, University of Chicago Press, 1987

<10> See Schaeffer and Jochen Schulte-Sasse:“The Prestige of the Artist under Conditions of Modernity” in Cultural Critique vol. 12, 1989, pp. 83-100

<11> See Croizer and Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen: “The Modern Woodcut Movement” in Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen (eds.): ibid., pp. 213-225

Bibliography:

Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen: “The Modern Woodcut Movement” in Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen, (eds.): A Century in Crisis. Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China, Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1998, pp. 213-225

Norman Bryson: “The Post-Ideological Avant-Garde” in Gao Minglu (ed.): Inside Out, New Chinese Art, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 51-58

Ralph Croizier: “Politics in Command, Chinese Art, 1949-1979” in Melissa Chiu and Zhang Shengtian (eds.): Art and China’s Revolution, Asia Society, 2008, pp. 57-73

Jacques Derrida: The Truth in Painting, University of Chicago Press, 1987

Carol Duncan: “The Art Museum as Ritual” (1995) in Donald Preziosi (ed.): The Art of Art History, Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 473-485

Clement Greenberg: “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939) in Greenberg: Art and Culture – Critical Essays, Beacon Press, 1961, pp. 3-21

Kuiyi Shen: “The Lure of the West: Modern Chinese Oil Painting” in Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen (eds.): A Century in Crisis. Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China, Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1998, pp. 172-180

Li Xianting: “Chinesische Malerei der Gegenwart – Rezeption und Integration vielf?ltiger Traditionen” in Dieter Ronte and Walter Smerling (eds.): China! Zeitgen?ssische Malerei, Kunstmuseum Bonn and DuMont Buchverlag, 1996, pp. 176-183

Mayching Kao: “Reforms in Education and the Beginning of the Western-Style Painting Movement in China” in Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen (eds.): A Century in Crisis. Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China, Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1998, pp. 146-161

Jean-Marie Schaeffer: Art of the Modern Age, Princeton University Press, 2000

Jochen Schulte-Sasse: “The Prestige of the Artist under Conditions of Modernity” in Cultural Critique vol. 12, 1989, pp. 83-100

Meyer Shapiro: “The Still Life as a Personal Object – a Note on Heidegger and Van Gogh” (1968) in Meyer Shapiro: Theory and Philosophy of Art: Style, Artist, and Society, George Braziller, 1994, pp. 135-141

Wu Hung and Christopher Phillips: Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China, University of Chicago Press, 2004