毛焰的执着

很多年来,毛焰的创作题材几乎限制在较小的范围。我不止一次听到圈子里的朋友对此议论纷纷。对于一个在人们视野中占据一席之地的艺术家,毛焰不图变易,或者说,变易始终只局限于方式的细微调整,其原因何在呢?毛焰不属于喜欢宏大叙事类型的艺术家,在一定程度上,他甚至对“大”问题、“大”形势怀有警惕。毛焰力求保持自己的连贯性和一致性,就他个体的特点而言,是相当明智的策略。其实,我们很多时候都被某种夸大了的幻觉弄迷糊了,对历史,对现状,对政治或伦理,都想发出自己的声音,并传授给他人。自然,这没有什么不好,有人愿意这么做,并且做得有效果,是非常值得称道的。问题是,许多人热衷对“大”问题、“大”形式和公共事件发言,是随大流和做应声虫。毛焰以自己个体的独特的方式作为立足点,虽然没有表面的轰轰烈烈,没有众星捧月的热闹,却在日积月累的创作里逐渐奠定了自己在当代艺术领域不可动摇的牢固地位。我一直认为,在当下,没有一个艺术家能够为艺术史全方位地提供全新的观念和创作,能做些添砖加瓦的工作,就已然十分了不起了。

毛焰的艺术才能早已得到公认,这是他的资本。我记得罗素说过,拥有才能并不稀罕,稀罕的是如何将才能使用好。这就回到刚才的话题——艺术家的类型问题。由于艺术创作所包含的因素极为复杂,言说的通道也各有不同,例如,社会学的,历史学的,心理学的,图像学的,等等,但没有一种方式可以把一个优秀艺术家完整呈现出来。很多时候,对某个艺术家的评说,有些类似于寓言里的瞎子摸象。例如,昆德拉说过,“卡夫卡学”毁坏了卡夫卡本身。同样,现在的“红学”研究,亦将《红楼梦》切得支离破碎。艺术创作的模糊性,与言说的明确性从本质上是冲突的。所以我特别警觉,不把艺术家笔下的活的作品当做尸体那样解剖,而宁愿服从创作的模糊性原则,不做过度解释。

不同的类型造就了艺术家不同的成就,这是无疑的。我在以前的评论文章中多次引用过博尔赫斯那句谶语般的名言:作家只能写他能写的东西,而不能写他想写的东西。艺术家一样,只能创作他能力范围里的作品。实际上,毛焰已经画出了他力所能及的作品。人们习惯于把艺术家类比为第一阵容、第二阵容什么的,毛焰毫无疑问是公认的跻身在第一阵容的艺术家,其独特性和原创性是不可取代的。而且,我在很多场合都听到同行对他高超的“手头”功夫赞不绝口。作为某一类型的艺术家,如毛焰这样不以观念取胜,不喜欢哗众取宠,踏踏实实地专攻自己所长,正是一种特别难能可贵的品质。我一向鄙视那种花里胡哨的乱来,鄙视在观念上偷窃一些他人余唾而冒充创新的花招,鄙视那些缺乏艺术才能却自认天才的江湖骗子。在我们这个乱象丛生的年代,毛焰的脚踏实地是一面镜子,让所有冒牌货自惭形秽。

有两个问题,一是关于毛焰在较长时间里以他的朋友老外托马斯为对象,反反复复,画了无数遍,托马斯成了毛焰现阶段的显著的符号。二是毛焰在较长时间里画法上的变化不大,似乎老是在重复自己。我的意思是,这两个问题都算不上“问题”,理由也是两点:其一,毛焰在一个地方挖井,并不断向深度掘进,试图在深度上做到无可匹敌,所以,题材或对象不重要,重要的是深入刻画;其二,毛焰的基本态度或已定型,画法在他那里便成为目的和手段的互相转换,既是现象又是本体,这样做的好处是符号性强,便于通过不同画面的同类画法,确立图式感和风格。就艺术史的事例看,除了少数艺术家(例如毕加索)面貌多样、变化多端,大部分艺术家则变化有限,所谓“一生只画了一幅画”的人比比皆是。不过,这一比喻浓缩了艺术家的全部精华。无论毛焰将对象定格在托马斯身上,还是别的人物,本质

是不变的。从一个艺术家成熟的表现分析,正如莫兰迪静物和巴尔蒂斯的形象,重复本身已被赋予哲学的意味。换句话说,以哲学的价值观作为依据,无非表明,艺术家的这种表达是具有认识论及伦理性质的。毛焰一而再再而三地描绘固定的对象,正是提供了这样的范本。

人们观察事物和判断事物往往把阶段性的现象看做全部,以偏概全。在我看来,无论哪个艺术家,都不存在旁人眼里的所谓长处和短处。因为艺术家的个体性是一个均衡的整体,他的长处或短处是交叉的和制约的。落实在毛焰身上,可以看到,人们常常把他的高超技巧当做主要话题,这显然是一种误解。当然,毛焰的绘画技巧几乎与生俱来,令人羡慕不已。但这只是他创作过程中信手拈来的东西。毛焰的真正贡献在于把技巧融化进了新鲜的视觉表达之中,也就是说,观赏毛焰的作品(无论是早期的,还是当下的),迎面扑来才气逼人之感,这体现在画面的方方面面,而不仅仅是单纯的“技巧”。毛焰运用的灰调子,运用的光斑和笔触,非常有效地塑造了他的对象,从而使作品的品质达到常人难以攀爬的高度。看似简单的表达,在毛焰那里轻而易举成为观众的视觉享受,这说明真正的技巧是具有生命的,是随着不同的作者而变化的,甚至技巧本身能够生发出与精神性同样的光辉。

对于一个优秀的艺术家来说,精神性是纲,技巧是目,纲举目张,这是无须争议的。但是,有没有离开技巧的精神性,才是争议之处。绘画的精神性问题是无限复杂的,很多直观的表达被批评家赋予“精神性”,其实是批评家在自说自话,是批评家为了方便抒发观念而夸大的东西。相反,隐藏在画面深处的精神性诉求往往被忽略和无视,这也是现实。在毛焰的作品前面,人们能够隐隐地发觉,作品背后晃动着的那个敏感、细腻、内敛、聪慧、孤傲、焦虑的影子。超脱和愿望和现实的渴望交结在一起,在这里,毛焰的个人情绪、个人愿望已经转化为某种人性的普遍性,他本人成了他者,通过作品,毛焰被自己对象化了。就这一点说,他的精神性显著地呈现出来,个体转化为普遍——成为某种气质、某种类型的存在。

一些批评家写的分析毛焰作品的文章,大多赞誉他对人物刻画的深度(技巧是另一个重点),同时还表明了这种深度既非社会学意义上的,亦非美学意义上的。毛焰本人则很少言说和解释自己的创作,一方面符合他个性上的特点,另一方面也说明作品自身的呈现比言说和解释更有说服力。我想指出,毛焰多年来执著地追寻自身内在的经验,不肯做丝毫妥协,是他的幸运。他的图式既浓缩了人的存在的复杂性,又将这种复杂性做了主观的简化,而正是这种主观的简化使他获得了个人价值,即前面所说的作者自身的对象化,如此,毛焰轻便地找到了他的通途,把自己引向明朗的未来。

李小山

2009年7月28日

Mao Yan's Perseverance

For many years, Mao Yan has limited himself to a relatively small range of subject matter. More than once I’ve heard heated discussions on this matter among friends in the art world. As an artist who holds a unique place in the eyes of many, Mao Yan has never sought to change this, or at least any changes that were made were limited to minute technical adjustments. Why is this so? Mao Yan isn’t the kind of artist who goes in for grand narratives. To a certain degree, he’s even wary of dealing with ‘big’ issues. Mao Yan strives to maintain coherence and continuity. With regard to his own particular characteristics, it’s a very wise strategy. We’ve all been confused at some point by some kind of illusion in life and whether it’s about history, the present day, politics or ethics, we all want to be able to pass on our own message to others. Naturally, there’s nothing wrong with this and those who want to, sometimes do it very successfully, which is commendable. The problem is that many people are very fond of speaking out about the ‘big’ issues in the public domain, blindly following the mainstream and simply become yes-men. Mao Yan makes his stand through his own unique means. On the surface, his work might not be spectacular and might not be at the centre of all the action but overtime it has gradually solidified a firm place for him in the contemporary art world. I have always believed that currently there isn’t any single artist who is able to provide art history with an entirely new concept or artwork. Being able just to add to it in a small way is already an outstanding achievement.

Mao Yan’s artistic ability was widely acknowledged early on, and forms his capital. I remember Bertrand Russell once said that to have ability was not rare, it was knowing how to use it well that was. This brings us back to what has just been touched upon – the question of different kinds of artists. Just as there are many complex factors involved in artistic creation, the channels used for verbal expression are also quite numerous, including sociology, historiography, psychology and iconography. But there isn’t any single means dedicated to the verbal discussion of an outstanding artist. Very often, reviews of artists seem to mistake a single part for the whole. Milan Kundera, for example, once said that ‘Kafkaism’ destroyed Kafka himself. Similarly, today’s over-zealous study of the Dream of the Red Chamber has completely torn its integrity to pieces. The ambiguity of artistic creation and clarity of verbal speech are fundamentally conflictual. Thus, I am extremely careful not to dissect like corpses artists’ work. I’d rather obey the ambiguity of creation, and lean away from excessive explanation.

Different kinds of artists are apt towards different artistic results; this is without doubt. In many previous articles, I’ve quoted Jorge Luis Borges’ prophecy-like dictum: writers can only write what they’re able to, not what they want to. Artists are the same – they can only create work that is within their ability’s range. In reality, Mao Yan has already produced works that has pushed the boundaries of his own abilities. People are used to classifying artists as first rate, second rate and so on; it’s needless to say that Mao Yan is widely acknowledged as being first rate. His individualism and originality are unparalleled. On many occasions have I heard fellow artists heap praise on his superb technique. To be the kind of artist, like Mao Yan, who hasn’t made their success through conceptual work and winning over the public with sensational statements but rather through specialised study of their own skills takes a particularly estimable quality. I have always disdained those who foolishly flaunt their showy skills, those who pilfer other’s left-over concepts, passing them off as blazing new tricks. I despise those charlatans who lack artistic ability and yet claim genius. In today’s chaotically sprouting world, Mao Yan’s down-to-earth and earnest nature is like a mirror that puts those imitations to shame.

There are however two problems to discuss. One regards the relatively long period in which Mao Yan has painted his foreign friend Thomas, painting him over and over. Thomas has become the clear symbol of Mao Yan’s current stage. The other problem concerns the long period over which Mao Yan’s style has undergone only very slight change. It’s like he is constantly repeating himself. In my opinion, however, these two problems aren’t really ‘problems’ at all, for two reasons. Firstly, it is in Mao Yan’s nature to dig a well and keep digging it deeper and deeper, as far as he can go, so the subject matter isn’t actually particularly important. What’s important is penetrating further into its depiction. The second reason is Mao Yan’s fundamentally settled attitude. His painting has become a mutual exchange between purpose and method, at once phenomenon and noumenon. The benefit of this is that it is powerfully symbolic, allowing him to use the same technique on different canvases, firmly establishing a sense of direction and style. As far as art history is concerned, except for a very small number of artists, such as Picasso, whose style was diverse and went through many transformations, most artists’ change is limited. Those that “only paint one painting in their lifetime” account for the majority. However, this analogy expresses the concentration of all of an artist’s quintessence in a single piece. Whether Mao Yan had stuck to the single subject matter of Thomas or if it had been someone else, the essence of it would not have changed. Analysing the mature workings of an artist, like the still lives of Morandi or figurative works of Balthus, one notices that the works often display a repetitive philosophical meaning already bestowed upon them. In other words, judging in philosophical terms, this kind of artistic expression is both epistemological and ethical. By repeatedly painting a fixed image, Mao Yan provides a means for such exploration.

When people observe things, or judge them, they often mistake a part for the whole. In my opinion, regardless of the artist, there are no such things as strong points and weak points in the eyes of onlookers because an artist’s individuality is a balanced whole. His strengths and weaknesses overlap and are constrained. As far as Mao Yan is concerned, people often take his extraordinary technique as their main subject but this is clearly misunderstood. Mao Yan was obviously born with the skill to paint, something so many are envious of. But this is just a gift that he acquired without his own effort. Mao Yan’s true gift is in his ability to use this skill in producing fresh visual expression. Appreciating Mao Yan’s work, whether it be early or current, one is faced with an explosion of artistic talent. It’s in every aspect of the canvas and is not only ‘technique’. Mao Yan uses grey tones, specks of light and brush strokes with incredible efficacy to portray his subjects with a quality few ordinary people are able to achieve. Painting at a glance so simple, and so effortless for Mao Yan, becomes visual pleasure for his audience. This demonstrates that genuine technique is alive, and changes in accordance with different artists. Technique itself is able to produce as much radiance as is esprit.

For a good artist, esprit is their guiding principle, technique their goal and once the principle grasps the goal, everything else falls into place. This is indisputable. But can there be esprit without technique? This becomes more controversial. The question of esprit in painting is incredibly complex. A great many observed expressions have been labelled ‘esprit’ by critics but they usually use the term at will, making it easier for them to express complex concepts. Meanwhile, the true esprit that is concealed in the depths of a painting is often neglected and remains unseen; this is how it is. Standing before a painting by Mao Yan, one can just perceive a sensitive and exquisite, restrained yet intelligent, aloof and apprehensively shimmering shadow in the background. It is here that the detachment, aspiration and pragmatic longing are cemented together and where Mao Yan’s individual emotions and hopes are transformed into a humane universality. Through his work he becomes the other, Mao Yan transforms himself into his subject. In this respect, his esprit is very clearly displayed – the transformation of the individual into the universal – it becomes a kind of temperament, a mode of existence.

The vast majority of critical reviews of Mao Yan’s work praise his profound figurative depiction, (his technique is another common emphasis), indicating that this depth is neither sociological nor aesthetic. Mao Yan, himself, rarely speaks about or explains his own work. This is partly a character trait and partly because the artworks themselves can be more persuasive than any spoken words that describe them. Mao Yan has persevered in his search for inward experience for many years, unwilling to make the slightest compromise. This has been his good fortune. His plan has been to concentrate the complexity of man’s existence before subjectively simplifying it. It’s this subjective simplification that gives him his individual values – namely the universalisation of the artist mentioned earlier. In so doing, Mao Yan is able to ease his way along the path that leads him onto a bright future.

Li Xiaoshan

July 28, 2009

- 毛焰的执着——李小山

- Mao Yan's Perseverance - Li Xiaoshan

毛焰的执着

很多年来,毛焰的创作题材几乎限制在较小的范围。我不止一次听到圈子里的朋友对此议论纷纷。对于一个在人们视野中占据一席之地的艺术家,毛焰不图变易,或者说,变易始终只局限于方式的细微调整,其原因何在呢?毛焰不属于喜欢宏大叙事类型的艺术家,在一定程度上,他甚至对“大”问题、“大”形势怀有警惕。毛焰力求保持自己的连贯性和一致性,就他个体的特点而言,是相当明智的策略。其实,我们很多时候都被某种夸大了的幻觉弄迷糊了,对历史,对现状,对政治或伦理,都想发出自己的声音,并传授给他人。自然,这没有什么不好,有人愿意这么做,并且做得有效果,是非常值得称道的。问题是,许多人热衷对“大”问题、“大”形式和公共事件发言,是随大流和做应声虫。毛焰以自己个体的独特的方式作为立足点,虽然没有表面的轰轰烈烈,没有众星捧月的热闹,却在日积月累的创作里逐渐奠定了自己在当代艺术领域不可动摇的牢固地位。我一直认为,在当下,没有一个艺术家能够为艺术史全方位地提供全新的观念和创作,能做些添砖加瓦的工作,就已然十分了不起了。

毛焰的艺术才能早已得到公认,这是他的资本。我记得罗素说过,拥有才能并不稀罕,稀罕的是如何将才能使用好。这就回到刚才的话题——艺术家的类型问题。由于艺术创作所包含的因素极为复杂,言说的通道也各有不同,例如,社会学的,历史学的,心理学的,图像学的,等等,但没有一种方式可以把一个优秀艺术家完整呈现出来。很多时候,对某个艺术家的评说,有些类似于寓言里的瞎子摸象。例如,昆德拉说过,“卡夫卡学”毁坏了卡夫卡本身。同样,现在的“红学”研究,亦将《红楼梦》切得支离破碎。艺术创作的模糊性,与言说的明确性从本质上是冲突的。所以我特别警觉,不把艺术家笔下的活的作品当做尸体那样解剖,而宁愿服从创作的模糊性原则,不做过度解释。

不同的类型造就了艺术家不同的成就,这是无疑的。我在以前的评论文章中多次引用过博尔赫斯那句谶语般的名言:作家只能写他能写的东西,而不能写他想写的东西。艺术家一样,只能创作他能力范围里的作品。实际上,毛焰已经画出了他力所能及的作品。人们习惯于把艺术家类比为第一阵容、第二阵容什么的,毛焰毫无疑问是公认的跻身在第一阵容的艺术家,其独特性和原创性是不可取代的。而且,我在很多场合都听到同行对他高超的“手头”功夫赞不绝口。作为某一类型的艺术家,如毛焰这样不以观念取胜,不喜欢哗众取宠,踏踏实实地专攻自己所长,正是一种特别难能可贵的品质。我一向鄙视那种花里胡哨的乱来,鄙视在观念上偷窃一些他人余唾而冒充创新的花招,鄙视那些缺乏艺术才能却自认天才的江湖骗子。在我们这个乱象丛生的年代,毛焰的脚踏实地是一面镜子,让所有冒牌货自惭形秽。

有两个问题,一是关于毛焰在较长时间里以他的朋友老外托马斯为对象,反反复复,画了无数遍,托马斯成了毛焰现阶段的显著的符号。二是毛焰在较长时间里画法上的变化不大,似乎老是在重复自己。我的意思是,这两个问题都算不上“问题”,理由也是两点:其一,毛焰在一个地方挖井,并不断向深度掘进,试图在深度上做到无可匹敌,所以,题材或对象不重要,重要的是深入刻画;其二,毛焰的基本态度或已定型,画法在他那里便成为目的和手段的互相转换,既是现象又是本体,这样做的好处是符号性强,便于通过不同画面的同类画法,确立图式感和风格。就艺术史的事例看,除了少数艺术家(例如毕加索)面貌多样、变化多端,大部分艺术家则变化有限,所谓“一生只画了一幅画”的人比比皆是。不过,这一比喻浓缩了艺术家的全部精华。无论毛焰将对象定格在托马斯身上,还是别的人物,本质

是不变的。从一个艺术家成熟的表现分析,正如莫兰迪静物和巴尔蒂斯的形象,重复本身已被赋予哲学的意味。换句话说,以哲学的价值观作为依据,无非表明,艺术家的这种表达是具有认识论及伦理性质的。毛焰一而再再而三地描绘固定的对象,正是提供了这样的范本。

人们观察事物和判断事物往往把阶段性的现象看做全部,以偏概全。在我看来,无论哪个艺术家,都不存在旁人眼里的所谓长处和短处。因为艺术家的个体性是一个均衡的整体,他的长处或短处是交叉的和制约的。落实在毛焰身上,可以看到,人们常常把他的高超技巧当做主要话题,这显然是一种误解。当然,毛焰的绘画技巧几乎与生俱来,令人羡慕不已。但这只是他创作过程中信手拈来的东西。毛焰的真正贡献在于把技巧融化进了新鲜的视觉表达之中,也就是说,观赏毛焰的作品(无论是早期的,还是当下的),迎面扑来才气逼人之感,这体现在画面的方方面面,而不仅仅是单纯的“技巧”。毛焰运用的灰调子,运用的光斑和笔触,非常有效地塑造了他的对象,从而使作品的品质达到常人难以攀爬的高度。看似简单的表达,在毛焰那里轻而易举成为观众的视觉享受,这说明真正的技巧是具有生命的,是随着不同的作者而变化的,甚至技巧本身能够生发出与精神性同样的光辉。

对于一个优秀的艺术家来说,精神性是纲,技巧是目,纲举目张,这是无须争议的。但是,有没有离开技巧的精神性,才是争议之处。绘画的精神性问题是无限复杂的,很多直观的表达被批评家赋予“精神性”,其实是批评家在自说自话,是批评家为了方便抒发观念而夸大的东西。相反,隐藏在画面深处的精神性诉求往往被忽略和无视,这也是现实。在毛焰的作品前面,人们能够隐隐地发觉,作品背后晃动着的那个敏感、细腻、内敛、聪慧、孤傲、焦虑的影子。超脱和愿望和现实的渴望交结在一起,在这里,毛焰的个人情绪、个人愿望已经转化为某种人性的普遍性,他本人成了他者,通过作品,毛焰被自己对象化了。就这一点说,他的精神性显著地呈现出来,个体转化为普遍——成为某种气质、某种类型的存在。

一些批评家写的分析毛焰作品的文章,大多赞誉他对人物刻画的深度(技巧是另一个重点),同时还表明了这种深度既非社会学意义上的,亦非美学意义上的。毛焰本人则很少言说和解释自己的创作,一方面符合他个性上的特点,另一方面也说明作品自身的呈现比言说和解释更有说服力。我想指出,毛焰多年来执著地追寻自身内在的经验,不肯做丝毫妥协,是他的幸运。他的图式既浓缩了人的存在的复杂性,又将这种复杂性做了主观的简化,而正是这种主观的简化使他获得了个人价值,即前面所说的作者自身的对象化,如此,毛焰轻便地找到了他的通途,把自己引向明朗的未来。

李小山

2009年7月28日

Mao Yan's Perseverance

For many years, Mao Yan has limited himself to a relatively small range of subject matter. More than once I’ve heard heated discussions on this matter among friends in the art world. As an artist who holds a unique place in the eyes of many, Mao Yan has never sought to change this, or at least any changes that were made were limited to minute technical adjustments. Why is this so? Mao Yan isn’t the kind of artist who goes in for grand narratives. To a certain degree, he’s even wary of dealing with ‘big’ issues. Mao Yan strives to maintain coherence and continuity. With regard to his own particular characteristics, it’s a very wise strategy. We’ve all been confused at some point by some kind of illusion in life and whether it’s about history, the present day, politics or ethics, we all want to be able to pass on our own message to others. Naturally, there’s nothing wrong with this and those who want to, sometimes do it very successfully, which is commendable. The problem is that many people are very fond of speaking out about the ‘big’ issues in the public domain, blindly following the mainstream and simply become yes-men. Mao Yan makes his stand through his own unique means. On the surface, his work might not be spectacular and might not be at the centre of all the action but overtime it has gradually solidified a firm place for him in the contemporary art world. I have always believed that currently there isn’t any single artist who is able to provide art history with an entirely new concept or artwork. Being able just to add to it in a small way is already an outstanding achievement.

Mao Yan’s artistic ability was widely acknowledged early on, and forms his capital. I remember Bertrand Russell once said that to have ability was not rare, it was knowing how to use it well that was. This brings us back to what has just been touched upon – the question of different kinds of artists. Just as there are many complex factors involved in artistic creation, the channels used for verbal expression are also quite numerous, including sociology, historiography, psychology and iconography. But there isn’t any single means dedicated to the verbal discussion of an outstanding artist. Very often, reviews of artists seem to mistake a single part for the whole. Milan Kundera, for example, once said that ‘Kafkaism’ destroyed Kafka himself. Similarly, today’s over-zealous study of the Dream of the Red Chamber has completely torn its integrity to pieces. The ambiguity of artistic creation and clarity of verbal speech are fundamentally conflictual. Thus, I am extremely careful not to dissect like corpses artists’ work. I’d rather obey the ambiguity of creation, and lean away from excessive explanation.

Different kinds of artists are apt towards different artistic results; this is without doubt. In many previous articles, I’ve quoted Jorge Luis Borges’ prophecy-like dictum: writers can only write what they’re able to, not what they want to. Artists are the same – they can only create work that is within their ability’s range. In reality, Mao Yan has already produced works that has pushed the boundaries of his own abilities. People are used to classifying artists as first rate, second rate and so on; it’s needless to say that Mao Yan is widely acknowledged as being first rate. His individualism and originality are unparalleled. On many occasions have I heard fellow artists heap praise on his superb technique. To be the kind of artist, like Mao Yan, who hasn’t made their success through conceptual work and winning over the public with sensational statements but rather through specialised study of their own skills takes a particularly estimable quality. I have always disdained those who foolishly flaunt their showy skills, those who pilfer other’s left-over concepts, passing them off as blazing new tricks. I despise those charlatans who lack artistic ability and yet claim genius. In today’s chaotically sprouting world, Mao Yan’s down-to-earth and earnest nature is like a mirror that puts those imitations to shame.

There are however two problems to discuss. One regards the relatively long period in which Mao Yan has painted his foreign friend Thomas, painting him over and over. Thomas has become the clear symbol of Mao Yan’s current stage. The other problem concerns the long period over which Mao Yan’s style has undergone only very slight change. It’s like he is constantly repeating himself. In my opinion, however, these two problems aren’t really ‘problems’ at all, for two reasons. Firstly, it is in Mao Yan’s nature to dig a well and keep digging it deeper and deeper, as far as he can go, so the subject matter isn’t actually particularly important. What’s important is penetrating further into its depiction. The second reason is Mao Yan’s fundamentally settled attitude. His painting has become a mutual exchange between purpose and method, at once phenomenon and noumenon. The benefit of this is that it is powerfully symbolic, allowing him to use the same technique on different canvases, firmly establishing a sense of direction and style. As far as art history is concerned, except for a very small number of artists, such as Picasso, whose style was diverse and went through many transformations, most artists’ change is limited. Those that “only paint one painting in their lifetime” account for the majority. However, this analogy expresses the concentration of all of an artist’s quintessence in a single piece. Whether Mao Yan had stuck to the single subject matter of Thomas or if it had been someone else, the essence of it would not have changed. Analysing the mature workings of an artist, like the still lives of Morandi or figurative works of Balthus, one notices that the works often display a repetitive philosophical meaning already bestowed upon them. In other words, judging in philosophical terms, this kind of artistic expression is both epistemological and ethical. By repeatedly painting a fixed image, Mao Yan provides a means for such exploration.

When people observe things, or judge them, they often mistake a part for the whole. In my opinion, regardless of the artist, there are no such things as strong points and weak points in the eyes of onlookers because an artist’s individuality is a balanced whole. His strengths and weaknesses overlap and are constrained. As far as Mao Yan is concerned, people often take his extraordinary technique as their main subject but this is clearly misunderstood. Mao Yan was obviously born with the skill to paint, something so many are envious of. But this is just a gift that he acquired without his own effort. Mao Yan’s true gift is in his ability to use this skill in producing fresh visual expression. Appreciating Mao Yan’s work, whether it be early or current, one is faced with an explosion of artistic talent. It’s in every aspect of the canvas and is not only ‘technique’. Mao Yan uses grey tones, specks of light and brush strokes with incredible efficacy to portray his subjects with a quality few ordinary people are able to achieve. Painting at a glance so simple, and so effortless for Mao Yan, becomes visual pleasure for his audience. This demonstrates that genuine technique is alive, and changes in accordance with different artists. Technique itself is able to produce as much radiance as is esprit.

For a good artist, esprit is their guiding principle, technique their goal and once the principle grasps the goal, everything else falls into place. This is indisputable. But can there be esprit without technique? This becomes more controversial. The question of esprit in painting is incredibly complex. A great many observed expressions have been labelled ‘esprit’ by critics but they usually use the term at will, making it easier for them to express complex concepts. Meanwhile, the true esprit that is concealed in the depths of a painting is often neglected and remains unseen; this is how it is. Standing before a painting by Mao Yan, one can just perceive a sensitive and exquisite, restrained yet intelligent, aloof and apprehensively shimmering shadow in the background. It is here that the detachment, aspiration and pragmatic longing are cemented together and where Mao Yan’s individual emotions and hopes are transformed into a humane universality. Through his work he becomes the other, Mao Yan transforms himself into his subject. In this respect, his esprit is very clearly displayed – the transformation of the individual into the universal – it becomes a kind of temperament, a mode of existence.

The vast majority of critical reviews of Mao Yan’s work praise his profound figurative depiction, (his technique is another common emphasis), indicating that this depth is neither sociological nor aesthetic. Mao Yan, himself, rarely speaks about or explains his own work. This is partly a character trait and partly because the artworks themselves can be more persuasive than any spoken words that describe them. Mao Yan has persevered in his search for inward experience for many years, unwilling to make the slightest compromise. This has been his good fortune. His plan has been to concentrate the complexity of man’s existence before subjectively simplifying it. It’s this subjective simplification that gives him his individual values – namely the universalisation of the artist mentioned earlier. In so doing, Mao Yan is able to ease his way along the path that leads him onto a bright future.

Li Xiaoshan

July 28, 2009

- 面孔的历程——汪民安

- Facial Adventures - Wang Min'an

面孔的历程

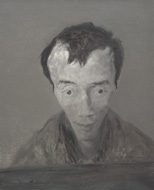

毛焰20世纪90年代初期的作品,诸如《小山的肖像》、《生日歌:一清先生》以及《伫立的青年》这些作品,画中的人物非常平静。这些人物都站立着(好像不是站在地面上,而是站在油彩上),既不喧哗,也不急躁,不是处在一个特殊的境遇中,也不是处在运动中和过程中,所有叙事性背景一扫而空。显然,这些肖像人物不是截取于生活中的一个片段,一个场景,一个瞬间,他们是有意地站立在那里。他们站立着,在干什么?在观望什么?因为完全没有叙事性背景,这里的站立和观望,只能看做是对绘画者本身的观望,他们站立着,似乎是在等待被画,在看着画家,在为绘画本身而存在。显然,他们没有什么能动性,没有什么饱满的力量向外爆发,也没有什么力量在被迫隐忍,相反,他们安静,安静得有些拘谨,好像知道在被一种特殊的眼光所看,他们的手都是内敛性的,手指不是向外伸展开来,而是向内地触摸甚至扣住自己的身体。更重要的是,他们目光平和,完全没有波澜在其中闪耀,完全没有被外部世界所惊扰,这些目光,没有流露出人物复杂的内在性,我们要说,他故意地藏起了这些内在性,毛焰似乎不愿意暴露人的丰富性。这些早期肖像画,与其说是探讨人本身,不如说是在探讨绘画本身:人物肖像不是为了人性事实存在,而是为了绘画事实而存在的。人物肖像吸引我们的,不是他们置身于一个戏剧性情景中,而是置身于一种特殊的绘画性情景中,置身于一种绘画的技艺之中。

一旦将人的内在世界隐藏起来,绘画就会全力以赴地注意人物的外在性本身,注意整个画面的结构配置本身,这个时候,我们看到绘画格外注意人物的轮廓本身,注意人的面孔,人的身体结构,人的服装,注重整个绘画色彩的配置本身。也就是说,注意肖像的形式本身,这些身体通常是呈锥形的,上身宽阔饱满,下身的腿则短而细,但面孔的器官高度写实,细腻且充满质感,这些使得人的身体有一种结构上的错置感。无论是“小山”,还是“一清先生”,他们的身体都被多层次的服装所包裹,他们居然都穿了三件外套!里面一件T恤(露出了领子的一角),中间一件衬衣(露出了局部),最外层一件西装或者背心(露出了整体)。这些服装,一层一层地,由局部到整体地暴露出来,随着它的层次由里到外地展开,这些服装各自不同的色彩也一层层地叠加起来,每件服装都是一个色彩,并和其他服装的色彩构成尖锐的对照,整个人体完全被不同的对照色彩所主宰。小山的黑T恤对照白衬衣,白衬衣对照着红背心,红背心对照着灰裤子,灰裤子对照着黑皮鞋。这些不同的色彩一块一块地拉下来,像是刻意缝合起来的一般,夺人眼目。不仅如此,人物的整个背景也被两种主导性色彩,大片的但并不纯粹的棕褐色和小片的同样并不纯粹的灰黑色所对照。色彩以一种对照的方式,在不停息地追逐和嬉戏。在此,毛焰的形式主义欲望一览无余。

但是,不久,毛焰决定重返人复杂的内心世界,在他90年代中期以后的作品中,他开始全力以赴地勾勒人的内在世界。这个时候,尽管毛焰还保持着他对人体结构的兴趣(比如对锥形人体的兴趣),还流露出他的技艺炫耀,但是,很明显,他添加了更多的东西,他试图画出人的内在性,人现在不仅仅是为绘画而存在的,不仅仅被绘画的目光所观看,而且,人还是作为人性事实而存在的。毛焰开始表达细腻的人性,同样是“小山”,但是,《小山的侧面》的小山,光着膀子,眼中流露出一丝不安,犹疑甚至恐惧,这不是那个毫无表情的小山,也不是那个穿戴整齐的小山,不是作为绘画对象存在的小山,不是一个被色彩嬉戏所完全覆盖的小山,而是一个“敏感”和“脆弱”的“小山”,一个暴露出人性事实的“小山”,我们被“小山”的内在性(而不是服装多层次的搭配)所吸引,被小山眼睛里所流露出来的东西所吸引,尽管这里只有一只眼睛。一只无助的眼睛,尽管这只眼睛在整个画面上占据的面积是如此之小,宛如画布上的一个破碎的小伤口。(还需要将另一只眼睛画出来吗?这另一只无法让我们的眼睛所看到的眼睛,难道不能被我们所感受到吗?)

人的内在性的表达,必须借助于目光。毛焰这个时期的作品,总是在人物的目光上精雕细刻。“小翟”的目光是借助白眼的方式来表达不信任和冷漠;“马余”细小而窄长的目光中流露出忧郁,以及对忧郁的肯定;“郭力”的目光敏感、聪慧,但是这种聪慧又不失尖锐;“Z”的目光暴露了隐秘的难以放开的激情;“小卡”的目光被紧张所塞满而显得冲动;“黑玫瑰”的目光毫无神采,在苍白和空洞中夹杂着冷漠;在所有这些作品中,“我的诗人”的目光最令人震撼,这里的眼珠似乎失去了生命力,似乎有一种死亡的气息盘踞在眼睛中,也因此盘踞在整个画面中。毛焰这个时期的肖像作品,是奉献给目光的。但是,这个目光不是对某一个特定瞬间的捕捉,这不是偶然的一瞥,这个目光,是透露气质的目光。毛焰不是借助偶然的场景来表达人的内在性,毛焰力图表达人的常性,表达人的一个长时段的稳定状态,表达人的一个特定时期的精神状态。因此,毫不奇怪,毛焰总是要清除叙事性,清除叙事背景。或者说,毛焰的画面背景,总是和人的精神状态相关的,而不是同外在事件相关的。毛焰不是通过运动来表达人物的,而是通过身体的结构本身,通过身体的一般状态,通过身体的姿态,更准确地说,是通过目光来表达人物的内心的。肖像人物的背景通常只有色彩,而无实物,因为实物会瓦解绘画中的目光重心,这点越来越清晰,以至于在《我的诗人》和《青年郭力:缅怀德拉克洛瓦》这两幅作品中,不仅没有实物,甚至连下半身也不见了,他只是凸现面孔和眼睛,他原先专注的服装,现在被高度地抽象化了,这些服装在这里被神奇地处理得像是山脉一样,头似乎埋在从平地上拱起来的山脉之中,埋在大地上,从而具有一种不朽的效果。在这些90年代中期的作品中,毛焰愿意将人理解成一个有深度的人,一个被丰富的内在性所充斥的人,一个有着魂灵的人。毛焰力图让这些魂灵在他的画面上获得不朽,获得魂灵的自我丰碑。

但是,不久,毛焰又逐渐从这个工作风格中退出了。他不再关注魂灵了,不再关注内在性了,或者,我们也可以换一种说法,他激化了前面的工作方式,将前面的方式推至极端,他以另一种方式来讨论人和魂灵,他对人采取了新的理解方式:人的绘画意义和先前的魂灵意义都不再存在了。从2000年之后的Thomas系列肖像来看,这与其说是人,不如说是人的轮廓。画面上的人同深灰色背景色调融为一体,犹如一个在雾天行走的人融入茫茫大雾之中。在这个大雾背景中凸现出来的是嘴唇、鼻子、耳朵、头发、眼睛(现在是同目光无关的眼睛,是闭着的眼睛)。这些器官,因为它们自身的不规则,因为它们自身从身体的圆满性中凸出或者凹陷下去,因为它们的形状(形式)本身,而从画面的混沌背景中脱颖而出;相反,另外一些身体部位,比如脸、额头和脖子,通常被画面吞没了。就此,毛焰似乎对身体的结构(更准确地说,是面孔的结构)充满了兴趣。对面孔上的器官,以及这种器官之间的关系充满了兴趣。这些器官不仅以一种特殊的形状从身体上突出来,而且,这些器官的形状构造本身似乎也是一个宽阔的世界,毛焰的这个系列,看不出魂灵的无限广阔性了,而是让人看到了器官本身的广阔性:每一个器官漂浮在灰色的无垠的背景中,每一个器官或许就是一个无限世界。

不仅如此,在毛焰这里,这个人体的面孔,很像一个孩子手中的魔方,被不厌其烦地进行摆弄和组合,他似乎变成了一个面孔解剖师,从各个不同的角度,反复地对准这些凸起的器官,毛焰在反复地画这个人,让这个人呈现不同的面孔。就此,这些作品,我们可以说它既是一个作品(一幅画),又是截然不同的作品(完全不同的画);同样,我们说,画面上的这个人,既是同一个人,又是截然不同的人。绘画在这里展现了绘画的悖论和人的悖论:一张画是自己又不是自己,一个人是自己又不是自己。不仅如此,人体在这里被赋予了一个特殊的考虑:一个人的面孔,我们每天所见到的面孔,真的是同一个面孔吗?一个人的面孔,面孔上的器官组合,真的具有一种完全的视觉统一性吗?毛焰似乎在这里挑战这种视觉统一性常识,一副面孔是由一系列的差异面孔形成的;一个统一性是由一系列差异性形成的。让我们再发挥一点地说:一个人,是由不同的人组成的;一个实在的人,是由一个虚幻的人组成的;一副面孔,是由一组器官组成的;而一个器官,则包含了全部的世界秘密,在这个意义上,我们可以说,一副面孔有自己的器官,反过来,一个器官也有自己的面孔,即世界的面孔。

文:汪民安

Facial Adventures

Mao Yan' work from the early 1990s, including "Portrait of Xiao Shan", "Happy Birthday ?Portrait of Mr. Yi Qing", and "Standing Youth", present very peaceful figures. They are all standing up, as if not standing on the ground but on the paint. They make not a sound and create no confusion. They are not situated into any one special environment, or in the process of movement or time. All narrative background has been erased. Obviously these portrait figures are not cut from one episode, scenario, or moment from life. They are put there standing intentionally. They are standing, but why? What are they doing? What are they looking at? Due to the lack of narrative background, this standing and looking can be considered as observation into the painter himself. They stand there seeming to wait to be painted. They look into the painter, living for the painting itself. Apparently, they lack initiative, are without any rich power to explode or strength for tolerance. On the contrary, they are so peaceful, so reserved, as if knowing being observed by one special gaze. Their hands all reach inside, fingers not reaching out, but closely buckling up their own bodies inwardly. What is more important, their gaze is so peaceful without any disturbance shining. Without any interruption from the outside world, they do not show off the complicated inward features of human beings. We must say that they deliberately hide such inwardness. Mao Yan seems not to be willing to expose the rich features of humankind. These earlier portrait paintings explore the subject of painting itself rather than humankind. The human portrait does not exist here for reasons of humanity but for painting itself. These figure portraits are attractive not because they are situated into one melodramatic scenario, but because they are embedded with a special painting technique.

Once the inner world of human beings is hidden, paintings shall go all out to attend to the outside features of figures and take care of the coherence of the overall painting. We can see his paintings pay special attention to the outline of figures, faces, physical structure, clothing, and the coherence of colours in the paintings. In other words, the forms of portraits are taken care of, which are most often taper-shaped, with upper part wide and strong and lower part thin and short. The organs on the faces are so realistic, delicate and qualitative that it makes the bodies look dislocated in structure. No matter whether it is "Xiao Shan", or Mr. Yi Qing, their bodies are all covered up with layers of clothes. They are dressed up with three overcoats, the inside T-shirt (the corner of the collar is exposed), one shirt in the middle (part of it is exposed), and the outermost western-tailored suit or vest (the whole of it is exposed). These clothes, layer by layer, are exposed from first a small section to overall. Along with the extension from interior to exterior at different levels, the different colours of these coats are folded together. Each garment is one colour that creates a sharp contrast with the other clothes. The overall human body is determined by the different contrasting colours. The black T-shirt of Xiao Shan contrasts with the white shirt, while the white shirt contrasts with the red vest and the red vest contrasts with the grey trousers which contrast with his black leather shoes. These different colours are pieced together intentionally to create a very sparkling vision. Not only that, the total background of the figures are contrasted by two leading colours, with a large majority of impure chocolate brown and a minority of impure grey black. The colours chase after one another restlessly in a contrasting manner. The desire for formalistic features of Mao Yan is here within presented completely. It was however not long before Mao Yan decided to turn to the complicated inner world of human nature. In his art works created in the mid-1990s, he went all out to depict the inner world of human nature. At that time, even if Mao Yan kept his interest in human physical structure, for example, his interest in tapering form, he still shed any traces of showing off his technique. However, it is obvious that he added a lot of other things. He intended to paint the inward features of humankind which did not live only for painting and were not viewed only by painting a gaze. Furthermore, humankind still exists as a humane fact of life. Mao Yan started to express an exquisite humanity. It was still the same "Xiao Shan". However, Xiao Shan in "Xiao Shan in Profile", with his arms bare, gives off an air of instability, suspicion and even fear in his eyes. This is not the Xiao Shan who had no facial expression, neither was this the tidily dressed Xiao Shan or the Xiao Shan as an object of a painting, nor the Xiao Shan covered up by playful colours. He is the "Sensitive" and "fragile" Xiao Shan who exposes humane facts. We are so attracted by the inward features of "Xiao Shan" (rather than the outfit of all different layers of clothes) and the life from his eyes. Even though there was only one eye, one helpless eye, it takes up a huge area of the painting, like a broken wound (Does Mao Yan need to paint the other eye? Can't we sense the other eye which we cannot see? )The expression of human inwardness must rely on gaze. The works of Mao Yan at this time concentrated on the careful depiction of human gaze. The gaze of "Xiao Zai" relies on a supercilious look to express distrust and indifference. The small and narrow eyes of "Ma Yu" give out sentiments and confirmation of melancholy. The eyes of "Guo Li" are very sensitive and intelligent though very sharp at the same time. The gaze of "Z" exposes secretive and covered-up passion. The eyes of "Xiao Ka" are filled with tension that seem very impulsive. The eyes of "Black Rose" lack glamour, filled with indifference from pale and empty holes. Among all these works, the gaze of :My Poet" is the most striking with the pupils losing all vigor, as if the smell of death is locked into the eyes and hence completely surrounding the whole painting. The art works of Mao Yan during this period are dedicated to eyes which reveal temperament. This gaze does not capture one specific instant. It is never one casual look. Mao Yan does not apply occasional scenarios to express the inward features. He attempts to express the normality of humankind, the stable status over a long period of time or the spiritual status of humankind in one specific period. Therefore, it is not surprising that Mao Yan always deletes narrative features and backgrounds. In other words, the background of Mao Yan's paintings is associated with human spiritual status-quo, not related to any outside events. Mao Yan does not express his objects through movement, but through corporal structure, normal bodily status and poses. More accurately speaking, he depicts the human heart through eyes. There are only colours in the background of portrait paintings, and not any objects for fear of distracting the focus of the eyes in the painting. This trait becomes clearer in his later works. In the two works "My Poet" and "Young Man Guo Li", there is no actual object and the lower part of the body is not shown. Mao Yan only highlights the face and eyes. The clothes he used to focus on become more abstract and treated like mountains. The head seems to be embedded into the mountains rising up from the ground. Therefore, this manoeuvre creates one eternal effect. In his mid-1990s works, Mao Yan preferred to deal with people as humans with depth, humans filled with rich inward traits and souls. He intended to make these souls reach permanence and achieve a glamorous monument.

However, it was not long before Mao Yan retreated again from this working style. He did not attend to souls and spirits. He cared not for the inward features. In other words, he intensified his previous working method by pushing it to the extreme. He discussed humans and spirits in another manner and treated people with a new understanding. The significance of human painting and predestined spirits did not exist any more. From his series of portraits "Thomas", one finds more the profile of human beings, The figures are mixed up with the deep grey background colour, as if one person walks in deep fog. The mouth, nose, ears, hair and eyes (now eyes closed without anything to do with gaze) are highlighted from this foggy background. These organs, because of their irregular structure, either concave or convex form from the round-shaped body, and their own shapes/forms stand out from the chaotic background. On the contrary, the other parts of the body, for instance, face, forehead, and neck, are overshadowed by the painting. Here, Mao Yan seems to be full of interest in the physical structure, more accurately speaking, the structure of the face. He is deeply interested in the facial organs, and the relationship between these organs. They stand out not only because of their special form, but also by way of their structure's resemblance to the broader world itself. This series of Mao Yan's does not give off the extensive spiritual realm. Rather, it allows organs expose their own extensiveness. Each organ floats in the infinite grey background which might as well be an infinite world.

Furthermore, the faces of human nudes are dealt with like a Rubic's cube in the hands of children, which are tirelessly arranged and assembled. He seems to have become a facial dissector. From different angles, he focuses on the raised organs repetitively. Mao Yan paints one same person repetitively to present the different faces. These works can be seen as one work of art, one painting, or totally different works. Similarly, we say this person in the painting is not only one person, but also a totally different person. Painting presents a paradox of painting but also a paradox of humankind. One painting depicts himself but is at once not himself. One person is himself yet is at once not himself. The human body is enriched with one special consideration. Is the face of one person which we see everyday the same face? Does the combination of facial organs create one complete visual coherence? It seems that Mao Yan challenges the cohesive common knowledge of visual effect. One face is composed of all different faces. One coherence is constructed with a series of differences. Let us give it a deeper statement: one person is composed of all different persons and one real person is composed of one virtual person. One face is composed of a group of organs. One organ hides all the secrets of the world. In this sense, we can say that one face has its organs. One organ, on the contrary, also has its own face and the face of the world as well.

Text: Wang Min'an

- 毛焰的智慧——韩东

- Mao Yan's Wisdom - Han Dong

毛焰的智慧

艺术无不追求极端,尤其是当代艺术,在这点上艺术家们似乎已经达成共识。也许,区别就在于愚昧和智慧。愚昧的追求,将极端看成某种独立之物,趋近的方式直接而鲁莽。而智慧者只是在极端之间寻求张力。他的目光是虚的,在不确定中辩证地把握住事实的真相。艺术家的野心和能力皆由此给出。面对一极还是多极?极点之间的距离遥远还是接近?处理尽量遥远的多极是很多艺术家的梦想,剩下的问题仅仅是能力的跟进。无法纳入能力范围的多极,暴露了艺术家的贪婪,最终还是愚昧。而在能力范围内的多极,则使艺术家风流尽得,其艺术成品也趋于完善。

毛焰的智慧就在于他始终在自己的能力范围内活动。其次,他的能力指向多极。关于毛焰的能力我无须多说,在这方面他是天之骄子。但关于他的多极指向,却常被我们忽略。

被公认的毛焰的变法开始于十年以前,这之后,才有了“托马斯系列”。毛焰的这次转向并不是克服危机的结果—如很多艺术家的惯例,正好相反,他刚刚抵达某个巅峰。无论从舆论或是作品所呈现的品质看,荣光正徐徐降临。大家翘首以待之际,毛焰却古怪出走。

逃离荣誉是艺术家该干而往往不会干的事,毛焰却做到了。当然艺术并不关乎道德修养。毛焰的运动自有其物理的逻辑,即是向另一极的运动。

毛焰的一极并不是对另一极的否定,并非是死而后生,远没有那么悲壮和野蛮。他要游刃有余得多,也智慧从容得多。“托马斯系列”和“前托马斯时期”之间构成了某种比对的关系,强大的张力弥漫于这一空间中。

“前托马斯时期”所描画的对象有隐约的社会身份,有年龄特征和完整的姿态造型。其后,这些因素被简化了,但个性深度却得到加强。从“托马斯系列”开始,所有的这些“可说”的内容都不复存在了,毛焰“空”了,“托马斯”只是徒具人形而已。从“前托马斯时期”到“托马斯系列”是从“有”到“无”的跨越。但这远远不够。对毛焰而言,“空”并非是“空”,并非只是为了和“前托马斯时期”保持呼应。在“空”之内不能只知有“空”,还得仪态万千,还得繁花似锦。

“托马斯系列”的“空”可表述为“空即是色”。尽可能地抛开肖像绘画中的意义因素,这“色”的重任就落到了纯粹的绘画语言上。于是毛焰便可大显身手。因为,就能力而言,这项工作的确非毛焰莫属,舍毛焰其谁。

“托马斯系列”和“前托马斯时期”之间构成了系列与时期的比对,而在“托马斯系列”之内,“空”与“色”相互映衬,使艺术品质趋向一个具体的极限。这就像地球绕太阳公转,同时也自转。毛焰的艺术宇宙格局恢弘,又巨细无遗。

题外话。艺术家终其一生,如果成立,便会有完美的宇宙诞生。这宇宙不在乎规模大小、外观壮丽或者包罗万象,仅在于有效的逻辑运作。

题外话二。艺术宇宙的逻辑不可预置,只可能伴随艺术宇宙的打开而呈现, 一如真实的宇宙及其法则。对艺术家和观赏者而言都是如此。在这宇宙打开之前,艺术家多了一点预感,在这之后,或可追加一份顿悟。他们正是为这多出的一点点东西而工作的。

“托马斯系列”之后,毛焰的预感和“色”有关。《巴黎·巴黎》、《戴帽的丽莎》、《Kim》等几幅近作所画的都是女性。女性是“色”的标志、“色”之符号,堕落而艳丽的女性更是“色中之色”。这批作品与“托马斯系列”截然不同,并且因其不同而和“托马斯系列”构成了比对关系,因此有理由认为这是毛焰的又一次转向,相对新的极点运动的开始。同样不是因为创造力上的穷途末路,同样开始于一个辉煌的巅峰。毛焰的目的也不只是和此前的工作拉开距离,在“色”之内别有探究的天地。

和流行的艳俗艺术不同,毛焰不是将高雅的意象降低为低俗近人的东西,恰好相反,他把低俗近人的东西加工为高端脱俗的。所画的对象越是堕落艳丽,绘画语言就越是高超精纯,甚至于雅致。按他自己的话说,竟然画出了古意。“色”的现实内容就这么被“空”掉了。因此毛焰的“色”并非是“色”,“色”中有“空”,有空虚、空无,有超越。将其表述为“色即是空”是题中应有之意。

从“有”到“无”,从“空即是色”到“色即是空”,毛焰的艺术呈现出趋向多极的运动。在极点之间毛焰构造出强大的平衡,展现了其间绵绵不绝的张力。追随直觉和预感的毛焰,最终踏上了辩证之途。

最后我想说,好的艺术家都是天生的辩证法大师。

韩东

2008年1月19日

Mao Yan's Wisdom

Art invariably involves pursuing extremes, especially contemporary art. On this point, artists are more or less agreed. Perhaps what then makes the difference is their degree of ignorance and wisdom. An ignorant pursuit takes the extreme to be some kind of independent object and adopts a direct and rash approach to its attainment. Pursuit by a wise man, on the other hand, simply involves exploring the tension between extremes. A wise artist's gaze is empty as he dialectically grasps the ultimate from ambiguity. An artist's careerism and ability lie herein. Should one confront a single extreme or multiple different poles? How far apart do they lie? Being able to manipulate a number of distant extremes is a dream of many artists, but in order to realise such a dream, their ability must be able to follow suit. Trying to control a number of extremes beyond one's ability can reveal an artist's greed, and ultimately his ignorance, while multiple extremes being handled within the scope of one's ability can display an artist’s talent. Such an artist's work will tend towards consummation.

Mao Yan's wisdom lies in the fact that he has always worked within the scope of his own ability. Secondly, his ability reaches out to different extremes. One doesn't want to dwell too much upon Mao Yan’s technique; he has quite simply been blessed. His tendency towards multiple extremes is however an aspect too often neglected.

Mao Yan's generally recognised change of direction began ten years ago. Only after this did the 'Thomas series' appear. This change of direction for Mao Yan was far from being the result of overcoming any kind of crisis, as is the case for so many artists. On the contrary, it came just as he had reached a peak. Both general opinion and indeed the quality of his work at the time are testament to the gradual shining of his career. Everyone was eagerly anticipating his next move, and yet strangely enough, Mao Yan walked away from it all.

Fleeing from fame is something artists should do but so often don't manage to. Mao Yan managed it. But of course art is not about moral cultivation and Mao Yan's actions had their own material logic, namely the turn towards another extreme.

The pursuit of another extreme for Mao Yan was certainly not a denial of the other; luckily it's not as sad and savage that one must die for the other to emerge. He wanted to get as much from it as possible but was wise enough not to rush towards it. There is thus a contrast formed between the 'Thomas series' and the 'pre-Thomas period' that is filled with powerful tension.

The subjects depicted in 'pre-Thomas period' paintings had faint social identities with age-bearing traits and complete, posed compositions. Later, these elements were simplified but the individuality of his works became stronger. Starting with the 'Thomas series', everything that 'needed mention' is no longer present. Mao Yan is 'empty' and 'Thomas' no more than a human shape. The leap from the 'pre-Thomas period' to the 'Thomas series' was one of 'substance' to 'nothingness', but this explanation is far from adequate. As far as Mao Yan is concerned, 'emptiness' is not 'empty' and is not just there as an echo to his pre-Thomas work. There is a distinguished air of elegance and beauty, intellect and artistic efflorescence within the emptiness.

The'emptiness' in the 'Thomas series' seems to express that 'everything empty is colour'1 . Trying his utmost to disregard the significant elements of portraiture, the heavy responsibility of colour falls to pure and unadulterated painting. Consequently, Mao Yan is able to display his skills fully because in terms of ability, this work could be no one other than Mao Yan's and without him it wouldn't exist.

The 'Thomas series' and the 'pre-Thomas period' can be contrasted but within the 'Thomas series'itself, emptiness and colour set each other off, pushing the work towards the limits. It's like a revolution of the earth around the sun; both are moving of their own accord. Mao Yan’s artistic universe is extensive, where big and small no longer exist.

An aside: If successful, an artist could very well create a perfect universe within his lifetime. Such a universe wouldn’t care for being large or small, externally magnificent or all-inclusive; it would just need to operate efficiently of its own accord.

Another aside: The logic of an artistic universe is impossible to prepare for, one can only follow what such a universe opens up and presents to us – just like the real world and its respective laws. This is same for both artists and onlookers. Before such a universe opens itself up, artists might have some kind of presentiment, to which they’ll probably add an element of inspiration. Having this tiny bit extra is exactly what they are working towards.

Since the'Thomas series', Mao Yan has had a presentiment concerning lust. Recent works such as Paris, Paris, Lisa Wearing a Hat, and Kim all feature female subjects. Women are the mark and symbol of lust. Degenerate and tacky women suggest even greater degrees of sexuality. This batch of work is completely different from that of the 'Thomas series' and as such creates a strong contrast with it. Consequently, it's fair to say that Mao Yan has had another change of direction, towards another new extreme. Once again, this is not because his creativity has come to a dead end, on the contrary, it has once again come at the time of a glorious peak. Mao Yan isn't just striving to distance himself from his previous work, there is a whole new 'lustful' world to explore.

In contrast to the popular gaudy artwork of today, Mao Yan doesn't vulgarise elegant concepts in order for his work to be attractive; it is quite the opposite. He is reworking vulgar subject matter into refined extremes. The more degenerate and tacky the subject, the more superbly refined is the painting, to the point that it becomes tasteful. He has even surprised himself of the classical style and taste of the work. The actual meaning of the 'lust' represented has thus become 'empty'. As such, Mao Yans 'pornography'is far from being pornographic. It is empty, devoid of meaning, unreal, and transcendent. It's true meaning lies in the depiction of the Buddhist saying, 'everything with colour is empty.'

From 'substance' to 'nothingness', from 'everything empty is colour' to 'everything with colour is empty', Mao Yan's art displays movement towards multiple poles. Mao Yan constructs a formidable balance between the different extremes, revealing the endless tension between them. Following his intuition and presentiments, Mao Yan ultimately finds himself on a dialectical path.

I would finally like to add that good artists are inherently all masters of dialectics.

Han Dong

January 19, 2008

1. Translator's Note: A transliteration of a term from the Heart Sutra of the Buddhist Canon, often translated as, 'The immaterial is the material'.

- 毛焰与托马斯——舒可文

- Mao Yan and Thomas - Shu Kewen

毛焰与托马斯

毛焰是他画的那些肖像人物的旁观者,还是创造者?也许所有的肖像画都是画家的创造物,不过,毛焰的肖像画与他的对象距离更远。所以,毛焰的这些画面并没有提供判断或一种乐趣,故事似乎并不在一个静止的画面停留,而是一种向一个未知的目标的行走,作为叙述者的画家与观看者处在同样的未知状态,因为毛焰在创作中有效地屏蔽了判断性的表达,这些肖像画提供给我们一种很特殊的心理感觉,诱使观看者也感觉是画家的同谋,参与着他的认知之行。那几乎是一种永无答案的解读之行,也是毛焰肖像画的趣味所在。

为什么画一个叫做托马斯的白人?这个问题如果以无所不为的当代艺术立场来看,是个浪费时间的问题。但托马斯肖像确实让人印象深刻。从1999年开始画托马斯肖像,毛焰至今画了近百幅。10年的时间里,画面上的托马斯也从一个具体的肖像,转变成了一个少有情绪特征的、冷而静的形象,只是一个形象。这个形象的存在似乎深藏在一个遥远的地方,只有通过毛焰绘画的笔触,我们才能感觉到一种存在的气息,却又是难以把握的、需静心跟随才能隐约体会的缥缈气息。

那年,环碧堂给毛焰做展览之前,对毛焰,我形成了一种印象,他在创作上热情不足,懒散有余,换一种说法,他在以一种停顿的策略应对一个他不大信任的艺术环境。1991年,毛焰从中央美术学院毕业到了南京,随后的几年,中国的当代艺术渐入佳境,艺术表达的方式尽数出现,而毛焰却在这个大好环境中生出一份不自信。他反省自己,好像没有那么强的表达欲望,或没有足够的表达能力。开始的时候,他对所谓的个人视角的表达只是觉得很乏味,好多年之后,他比较明确地感觉,对什么事情都有所表达会造成一种错觉,所有的表达变得理所当然、煞有介事,也很危险。

谈论当代艺术的问题,似乎是一种冒犯,谈论当代艺术的理由,似乎是更被看重的,或定义什么是当代艺术似乎是重要的。但对毛焰而言,艺术的问题并没有发生那么大的变化,终归还是人的问题。

那时候,毛焰画了一批肖像,都是周围要好的朋友。他的生活范围很小,在一个极小的友人圈子里,很少参与南京本地的活动,也和北京有艺术节奏上的距离。我曾试探地问他是不是有点懒,因为与当代艺术的快速发展相比,他的工作量一直不大,常常一副休闲状,他过于客气,说,“其实很多事情也有所感受,但是我怀疑我自己的表达欲望和能力”。我用“人人都是艺术家”的口号反问,他只认可“人人都是艺术家”是人的一种权利,“但是如果没有相应的精神力量,只有疯狂的表达欲望,会让人厌烦,也很可怕。如果个人的视角缺乏历史感,也是很苍白的”,因为从他的学艺经历中,他不仅获得了艺术的训练,也形成了一种对艺术本身的敬畏之心。古旧的艺术理想,或关于艺术的想象,或来自他学习绘画的初始想象,在他绘画中成了一种准则,不敢妄自挥洒。

1996年的朋友肖像大概是在这个情绪背景下展开的谨慎尝试。这些肖像的名字只透露出他们是画家的友人,他们对于画家也许有特定的意义,对于看画的人这些名字能提供哪些信息,名字对画面是否也有描述性,答案基本是否定的。在毛焰的理由中,他希望在画面中能够与日常生活保持一段距离,之所以选择画要好的友人,主要是因为他们在文化中没有符号意义,能够避免卷入流行的解读。

他开始有意识地警惕着过度的情绪表露,希望在画面上能尽量地屏蔽个人痕迹,让画能自然而然地流露出来。那时候他画的黑玫瑰、诗人、朋友等确实有一种游离于整体气氛之外的冷峻气质,在画面上,那种可依据的、容易激发出情感力度的外在证据,诸如表情、环境、衣着等等都被删减得越来越无关紧要,只流露出很紧密的心理内容,以此构成一个个单纯而尖锐的画面。

1999年,毛焰开始画托马斯。托马斯何许人也?毛焰在1998年一个平常的饭局上认识了托马斯,此后他们经常和朋友在一起吃饭,喝酒,踢球。其实托马斯只是一个幌子,那时托马斯只是一个来中国学汉语的白人,很安静,朴素,很内向,表情没有明确的指向性,似乎是一个无关紧要的对象,但重要的是,以托马斯为形的肖像可以使毛焰远离那些有所表达的表面意义,画托马斯肖像的乐趣,是一种与创造个性的乐趣相反的,或无关的方向——用一个白人的形象来缓解近距离的形象容易引出的情感波动,最大可能地摆脱带有主观性的情感判断,这使毛焰回避了中国当代艺术中的一个很要紧的问题,即所谓的中国概念、中国符号等等。

这个形象使毛焰获得了一个不断深化绘画方式的途径,托马斯的沉静形象在情绪上是一种温度很低的形象,毛焰在选择托马斯的照片时,过筛子一样选择其中表现力最少、情绪似有似无的状态,以达到最自然、最不经意、最少画外音的呈现。

一种形象重复10年的必要性是什么?可以是为了市场,也可以在艺术中找到理由,比如为了强化一个概念,强化意味着一种自信,至少是相信某种图像生成的意义是需要强化的。而毛焰的重复,却是因为他的“不自信”,他觉得他没有画出更深层的意义。

这在毛焰的绘画中构成了一个有趣的空间,他提供的画面即是一个不断细化、不断接近他想象的深层意义,又似乎是一个永无答案的开放过程,在这个过程中,毛焰的画面上,色彩在淡化、立体感在减弱,笔触变得清雅精细,从中能够看到一种对“解题”的热衷和紧迫,但他采用了一种速度更慢、语调更缓的方式,每一幅画都带着对情绪欲望的克制,对恣意判断的警惕,在这两种有些对立的状态下,竟然平衡出一种谨慎的优雅和一种顽强的伤感。

在这中间,毛焰也画了一些女性肖像,似乎也是一种克制,在画托马斯的时候,有意穿插一些情色趣味的肖像来调节,避免任何意义上的过度。

于是,这个漫长的重复过程,好像模拟了一个生命体日复一日的生长性,通过这种绘画展开的空间与历史的连续性建立起联系,每一个画面上呈现的都是一种认知路途。毛焰的肖像画为此而努力,以此来超越个人情绪、超越琐碎经验对人的诱惑。

文:舒可文

Mao Yan and Thomas

Is Mao Yan a spectator or the creator of the portraits he paints? Whilst the portraits are indeed all creations of the artist, Mao Yan remains incredibly distant from his subjects. These paintings neither judge nor please, their story doesn’t stop at a motionless canvas but leads towards an unknown objective. As both narrator and spectator, Mao Yan resides in this same unknown space, shielding himself from passing judgement. The portraits leave us with a peculiar feeling, like the painter is conspiring to lure us in, to join him on his quest for knowledge. The quest is almost never-ending and therein lies the delight of Mao Yan’s portraiture.

Why paint a Caucasian man called Thomas? This might seem like an obscure question in light of 'anything-goes' contemporary art, but the portraits of Thomas do leave a very deep impression. Mao Yan began painting Thomas in 1999 and has since painted almost a hundred portraits of him. In ten years, the painted image of Thomas has changed from being a detailed portrait to being a calm figure with few emotions, essentially a form alone. This form’s existence seems to be hidden away in a distant land and it’s only through Mao Yan’s brush strokes that we can feel its breath. Even then it’s not easy to hold onto and only a peaceful mind is able to pick up on its lingering exhalation.

Before the year Chinablue gave Mao Yan a show, I had doubts about Mao Yan’s creative passion and drive. I felt that he was trying to deal with a lack of artistic confidence by stalling. Mao Yan had graduated from CAFA in 1991, after which he had moved to Nanjing. The years that followed saw Chinese contemporary art go from strength to strength with all forms of artistic expression emerging, but this same time saw Mao Yan’s own self-confidence wither. He began soul-searching, seemingly without a powerful enough drive to express himself, or perhaps without the means. Initially, he felt that so-called individual expression was tasteless but after many years came to realise that expressing anything could cause misconceptions and that all expression could ultimately become assumptive, pretentious and even menacing.

Seemingly, it’s offensive to speak about the problems of contemporary art, whilst discussing the reasons behind it is valued. Defining what contemporary art appears even to be important. As far as Mao Yan is concerned, the problems of art haven’t changed very much, in the end they are all problems that concern people.

Back then, Mao Yan’s portraits were all of his close friends. His sphere of activity was very small at the time, staying within a very small group of people and rarely taking part in local Nanjing life. He was quite removed from the artistic rhythm of Beijing. I asked him at the time if perhaps he wasn’t slightly lazy? Compared to the fast pace of contemporary art, his work rate has always been slow, often with unfinished paintings left stagnant. He politely said to me, “Actually, I’m moved by a lot of things but I question my own expressive ability and desire.” In response, I used the old catchphrase, “But everyone’s an artist.” He agreed with this idea and said that, “Everyone has the right to be an artist but if all they have is the wild urge to express themselves and lack the corresponding esprit, they can end up annoying people, it’s terrible. If their individual perspective lacks a sense of history then it also tends to fall flat.” Along his artistic path, he had not only received artistic training but had also developed a certain reverence for art itself. Antiquated artistic ideals and expectations of art that came from his initial study of drawing thus became his criteria for painting. He didn’t dare give them up and paint freely.

The portraits of his friends from 1996 were to unfold cautiously against this emotional backdrop. All that the names of these portraits revealed was that they were friends of the artist. Whilst they may have had special significance for the artist himself, what information could they provide for the spectator? Are the names in any way descriptive of the paintings? In general the answer is negative. Using Mao Yan’s reasoning, he wanted to keep a certain distance between daily life and his paintings and the only reason he chose to paint his close friends was because they weren’t culturally symbolic and would thus avoid any popular readings of them.

He began to guard against sentimental revelations on purpose, with the hope of shielding individual traits from the canvas as much as possible so that the paintings themselves could flow naturally. Paintings of the time such as Black Rose, Poet, and Friends had such a frosty quality, distanced from their surrounding atmosphere. Extrinsic evidence that could easily evoke emotions such as gestures, the environment, and clothing gradually became less and less important, leaving only very intense psychological elements that formed one after another pure and penetrating works of art.

In 1999, Mao Yan began painting Thomas. Who is Thomas, you might ask? Mao Yan met Thomas at a banquet in 1998, after which they often went out together with friends to have dinner, drink and play football. But Thomas was actually just a tool. At the time, Thomas was just another foreigner that had come to China to study Chinese. Quiet, simple, introverted and without any explicitly pointed expression, to most he wouldn’t have seemed like the most obvious subject for painting. But importantly for Mao Yan, portraits of Thomas’ would allow him to distance himself from expressing unwanted superficial meanings. The interest in painting Thomas was the exact opposite to that of painting personalities. Using a Caucasian man’s image avoided the sentimental reaction easily set off by all too familiar figures and it was the best way of getting rid of the emotional judgement brought about by subjectivity. This allowed Mao Yan to avoid one of contemporary Chinese art’s most serious problems, the so-called ‘Made in China’ concepts and symbols.

This subject has provided Mao Yan with a path to explore his art of painting. Thomas’ serene image is emotionally very cool and in choosing photos of Thomas, Mao Yan always picks out those which are the least expressive, seemingly without feeling at all, in order to achieve the most natural, carefree and least cluttered images possible.

What’s the point of repeatedly painting the same figure for ten years? It might be for the market but one can also find artistic reasons for this, for example to strengthen a concept. Strengthening here signifies a kind of self-confidence or at the very least a belief that the meaning produced by an image needs strengthening. Mao Yan’s need for repetition is down to his own lack of self-confidence, the feeling that he still hasn’t expressed the most profound meaning possible.

This has made Mao Yan’s painting quite fascinating as his canvases continue to become more careful and approach closer the deepest meaning of his imagination. It seems like a revealing process without any ultimate answer. In this process, the colour in Mao Yan’s paintings has become blander, the solidity weaker, and his brush strokes more meticulous. From this we can see a deep commitment to and urgency for solving a problem, but he adopts a slower pace and softer tone to do so. Each and every painting shows control of emotional desire and a wariness of reckless judgement. With the two of these partly conflicting attitudes, a cautious elegance and tenacious sentiment are unexpectedly balanced. Mao Yan has also painted a number of female portraits in this time which also appears to be a form of control. Whilst painting Thomas, he has inserted these occasional erotic portraits in order to regulate himself and avoid any other significance being drawn from his painting.

Mao Yan’s slow repetitive process simulates the day to day development of a living thing. Through the integration of the painted space with historical continuity, each painting represents a path towards knowledge. Mao Yan works hard at his portrait-painting with this aim in mind, at surpassing individual feelings and surpassing the seduction of people through trivial experience.

Text: Shu Kewen

- 毛焰:把绘画还原为绘画——HI艺术

毛焰:把绘画还原为绘画

时间:2009年8月10日

地点:南京幕府东路毛焰画室

采访:HI艺术

传统和当代,两种艺术的不和谐共存,使这个国家产生了明显可见的对比,并常常带给人一种很分裂的感受。但有些艺术家的职业生涯中,常常表现出一种常见的模式:一段早期对西方事物的热衷之后,紧接着是一个缓慢而渐进的对传统的回归。毛焰就是这样。即使在最严格的技术意义上而言,毛焰的绘画也属于最克制、最内敛和最受限定的绘画。

有人认为他已经out了,是因为他的画所沿袭的那些传统的品质,在现代化的机制中,已经被其它的价值取向取代。包括中国自身,完全不是以克制,虚无或宁静的品质而获得世人瞩目的。然而曾经中央美院的佼佼者,毛焰十数年如一日对这种品质的坚持,表明他对这种价值理想的认定,绝不只是凭空臆想那样简单。

关于创作

记者:“托马斯”的这个形象,对你意味着什么?

毛焰:托马斯作为一个形象,作为我的朋友现实意义之外的是,从一开始他就具有很虚无的特性,他不代表什么意思。其实他本身就具有一种虚无的性质,没有特别的意义,比如说他是欧洲人,但他是一个卢森堡人,也不是说很能代表欧洲。对于中国符号、中国形象,我一直没什么概念,也没兴趣,我选择了回避这个问题。

记者:那这10年间,就“托马斯”而言,你强化什么,弱化了什么?

毛焰:我一直比较迷恋于这种绘画语言,就是在中国绘画的语境中,画是展现意境的,与现实的表示方式是有距离的,我愿意在这个方面去投入时间。可以这样讲,实际上我弱化的就是绘画表面的东西,特别是很多人认为我技巧很好,这恰恰不是一个问题,从来就没有那个。强化的是我对绘画的认识。包括对绘画道理的认识,以及我对自身和情感上的认识,它们都融化在我的绘画面貌之下。是虚无的、平静的,轻微的,无色无味,没有太多的情绪化。包括这几年当中,我都采取了一种闭着眼睛的神态,就是不表达,在场的都很自然。

记者:你刚才说到你对绘画的道理和认识是什么?

毛焰:十几年前,很多艺术家会谈到一个问题,“他的生活方式决定了他的艺术方式”,但我很小的时候,我的很多生活是绘画给我带来的,我在绘画上的变化和学习过程,在里面体会到的道理,反过来指导我的生活,包括影响我的生活方式。实际上我觉得谁决定谁没有区别,只要你不刻意逐之。我整个绘画的过程都是顺其自然过来的,随便画了一个东西,有的朋友就说,你看新的感觉出来了。但是我觉得所谓新变化根本不是变化,我根本就没有想变化什么。可能是我很早就确立了自我方式,我不能说“很自我”,但是你们那么觉得。随着我对绘画的理解,反过来更加坚定我的生活方式,坚定我的生活态度,效法自然。

记者:“托马斯”的画是有序的吗?

毛焰:这么多年的这一个系列,实际上我觉得就是一个作品,这是我以前始料未及的,这其中也包括了我的省事、习惯和惰性,也因为没有东西能够激发我新的欲望。但当这个系列到现在的时候,我又有一种踏实的感觉。我才发现实际上我是很充实的,我现在才知道我要清楚地干什么,表达什么。

记者:是什么呢,表达什么?

毛焰:在我某一部分画得比较细腻的作品当中,我觉得那种语言是需要千锤百炼的,我不喜欢用现成的东西。而这个绘画的过程,并没有太多的痕迹,类似每天打坐一样的感觉。对我来讲,重要的不是画完那几张画,我特别需要这么一个过程,比我的作品更重要。就像说“静则生灵”,这个过程让我能感受到很多东西。我从小就是一个很躁动的人,欲望特别强,包括物质欲,对自己的绘画能力深信不疑。到现在,我越来越觉得你通过你的能力获得的东西都微不足道,对我来讲,能够在越长的时间能够处在这个过程当中,很有限的,很理性的,很自然细腻的过程中,我觉得美妙之极。

记者:栗宪庭在写到你的那篇《写实主义的探险》中,留下一个问题,说他也不知道是民族性导致你所说的克制,还是你的个性什么使然?

毛焰:栗老师谈的其实也包含了他自己的思想。比方说你不能永远只看到当代,因为这十几年里的一个概念是必须当代,你要当代当代。我觉得你如果只是看到当代,而缺乏一种历史感的话,那就是鼠目寸光,视野非常狭隘,你的个性宣泄也好,表达也好,是非常有限的,非常轻薄的。我老在想,我画到现在,我的目的是什么?我希望能获得的绘画是什么?而不能简单由着我的性格,我的个人习惯在走。并不是说我们现在就可以毫无顾忌,毫无障碍的表达自我,实际上远远不够,好多东西你都还不具备。我十四五岁就学习油画,当时的一切都是关于西方的,翻译过来的文史哲,诗歌,所有的所有。也一直大量看西方的作品,画册,从古典一直到当代,当时对那些东西都是趋之若鹜,如饥似渴,如数家珍,一直到现在都还有这种感觉,有点失控,你对有些东西了如指掌的同时,你对你家的东西所知太有限了,确实感觉这是一种生理的反应。随着成长,传统像电流一样的穿身而过,你不可能漠视这种联系。确实有一个很大的冲动,对于你背后的中国传统文化,你有这个愿望想去感受它,了解它。一旦有这种意识,那个是非常巨大的能量,你会发现自己的单薄和有限。你必将会产生一种感受和态度,或者一种感同身受的情感。这本身也很虚无。事实上,所谓你增加的很多认识,恰恰不是为了表达,也不需要表达,或者说表达的对象不一样。我觉得从这个角度来讲,艺术家表达并不是说不够,是太多了。我们现在所谓的表达对象都太现实了,太当代了,太眼前了,太具体了,实际上这种表达很多时候都是一厢情愿。

记者:但不管怎么说,你的绘画被认为是同时呈现出传统性和当代性并置的那种面貌?

毛焰:首先,这不是对立的两个东西。到今天为止,我仍然热爱很多西方的古典绘画,它们对我非常重要,已经不仅仅一个具体而实用的学习工具,就是一种精神上的感受。而所谓的现代性,我觉得就是你的个人性,你的个人观点,个人角度,个人的表达方式。这个对于我也很自然,很多东西是逐渐形成的,只要有那么一丁点儿加进去,个人的趣味、能力、愿望,到一定的时候一定会有化学反应的,就成了所谓的当代性。

记者:这个过程没有经历过矛盾吗?

毛焰:与之相对的,刚才说到,你一定争取表达你个人的理解,你的认识,你的角度,我在绘画的语言方式上就有一定有我自己的理解和认识,它不简单也不表面,你不能是虚高的,也不能是低的。这个是关于艺术家的创造力的问题,只要有那么一丁点东西,这种创造力就存在。我一直不太会讲个人风格这个事情,我不喜欢“风格”这种说法,太简单化了。我讲的就是一种语言方式。包括说,你这张画的时间都是一种方式,它的尺寸也是一种方式,它的表面的质地也是一种方式。从那个时候,我将近10来年没画过大画,就画很小的画,而且画的题材非常非常单一,就这么一种状况。

记者:那传统和当代在你那里又是如何联系起来的呢?

毛焰:回到传统和当代的这种关系的时候,我觉得很多只是一种评论,或者一种分类。我觉得自己一点都不当代,但是,我又确实感觉到自己的某些有别于传统绘画的价值。比如我们说的油画语言,俄罗斯的绘画语言到现在还能在院校里产生作用。中国很多的艺术家,包括画画的,做装置的,仍很多受到欧洲当代的影响。但是对我来讲,这早就不应该是个过程了。你应该有你自己的语言,这需要更加细心,需要你坚持很长时间。比如说,我喜欢变数。同样的东西,别人只做一遍,我可能做二十几遍,三十几遍,我喜欢这种变数,对我来说是必须的。很简单的,就是你投入的时间、你的专注程度,这种过程越长,你的情感投入越细腻。我从来没考虑什么方式当代不当代,都不重要。你就按照你的性质,你的理解,实实在在地体现你自己的语言方式,这我觉得特别重要。你必须要有你自己的表达方式,哪怕是很安静很轻微的,但这就是使你有别于他人的表达方式。这种表达要建立在一些基本的品质上面,这和个人的审美取向有关,我认可的就是朴素、沉静、节制、细腻、纯净、微妙、不温不火、无色无味,这对我个人来讲是至关重要的一种方式。

生活与记忆

记者:你自己是一个自控能力很强的人吗?据说你很能玩儿,你昨晚不是又喝多了吗?

毛焰:你是想问我是否像我的作品吧?应该是,肯定是。确实,我画画的过程是极度安静的。平静,你从我画面上就能看出来。但生活中我恰恰是比较爱玩,好热闹的,爱喝酒爱玩乐的人。

记者:也包括对待情感吗?既然如此,我该怎么把这些统一起来呢?

毛焰:应该是,肯定是。但这些年我越来越趋于理性,因为我现在的年龄到这儿了,且我一直相信,什么年龄做什么样的事。有的东西对我来讲,已经过去了,结束了。没必要刻意去规划未来,也没必要过度怀念自己的从前,这对我来讲,也是一种自律、节制。我非常警惕某些方面的过度表达,如果一个艺术家要做过度表达,要宣扬自己个性的时候,是非常容易的。但我不善于这样,我不觉得我有百分之百的权利和理由去宣泄我的个性,这不是我理解的好绘画。所谓的那种淋漓尽致的表达的个性我是不相信的,那种过度渲染、过度表达的东西我都很讨厌。当然也有素质优秀的艺术家确实建立在他有一种很好的理解,很好的认识,很好的心态上面,他可以去发表。如果你没有这种个人性,而是张牙舞爪的,想怎么弄就怎么弄,这是特别不负责任的,特傻,特别土。

记者:你的童年是怎样的?

毛焰:我在1968年出生,我们家在湖南的一个大型厂矿,现在回想起来特别艰苦,如果没有我父亲给我带来的一切,可能记忆当中就会很灰暗,只有烟囱什么的。我父亲业余喜欢美术,按照现在的话讲,就是典型的文艺青年。他还喜欢拉乐器,写小说,经常被抽调搞宣传画的创作,他自己有很多遗憾,就把他一生的理想都寄托在了我身上。从小他带着我去看全国美展,去广州,长沙,都耐心给我讲解。我从很小的时候,就有了一个有别于那个枯燥的环境的另一个世界。他也根本不管这个行当以后会不会吃香,就满怀这种热爱一心一意把我培养成一个画家。而且他成功了,到了我考美院之前,我跟我父亲的这种关系在当地都已经很出名,说谁谁谁对他孩子的培养如何如何。

记者:你名字是他给你起的吗,也是一种寄托吗?

毛焰:名字倒不是。好象是我妈感觉这个字比较好。但是很有意思,当我考美院的时候,我妈妈又建议我改名字,她说,美院的教授看你的名字会觉得火焰的“焰”太狂了。我妈她是特别喜欢开玩笑的一个人,就建议我改一个字,因为考这种学,家长都紧张得不得了。她建议我改一个,特别搞笑,改成三个毛叠在一起——毳,我妈特认真的跟我讲这个字,说这个字特别好,念CUI。我说那大家该叫我“四毛”了。

记者:那你年少轻狂过吗?听说80后的美院毕业生中仍然流传着你的传说。

毛焰:我学画画的过程当中,在上美院之前,确实有过那种年少轻狂的阶段,因为学的很投入,也很早画画,在当地被人叫天才,甚至很多当时我父亲画画的那一辈就预测到我的未来。不可能不年少轻狂。甚至上高中的时候,跟我高中老师有严重的有矛盾,老师都认为我很轻狂。

记者:你们同届同学里在艺术上比较突出的都还有谁了呢?

毛焰:冯梦波、张方白、马堡中。确实,我们这一届有很多已经不在干这个事了。

记者:你一直画写实,老栗在那篇文章中也说到,写实这块留出的空间很小,你感觉如何?

毛焰:我前一段看了一个外国电影,讲一个从小被送进寺院的小喇嘛,他每天有一个小时念经,但是小孩连字都不认识,他的师父也从来不给他解释是什么意思,他也从来不想问,每天就是这样。在我看来,他也不需要知道什么意思,就是在这一个小时内,他是很平静的。第二,他常年这样生活,等到长大成人,他已经具备了这样一种定性,足够可以抵御他面对的极大丰富的世界,就是在那念经的过程中,他获得了可以抵御他必须抵御的东西的力量。对于我来讲,没有什么东西不是小的。但如果这个东西是你一生的理想,你灌输了你真切的情感,你一直坚持你的热爱,那很小的东西同时也会很大。在我这里最终回到人的根本状态,学习绘画的初衷,绘画对于我来说,尽管有时候有厌倦的时候,有很疲劳的时候,但是那些过于时髦的观点,比如人们一直在谈论“绘画死亡”了,根本不会触及到我的热爱,那个问题根本不存在。

记者:你经常提到的虚无感从何而来呢?

毛焰:学画学到94、95年,就开始有那么一种感觉。似乎学的也不错,但就发现你学的越多,学的越好,就越不满意,越厌倦。《道德经》里说,“为学日益,为道日损”。你每一天都要进步,每一天都要学习,但是你学习了很多以后,你的表现欲望就会越来越强,因你的能力增强。但是,这种表现欲在我看来是需要克服的,你不能去滥用你的能力,因为这种能力是缺乏根基,缺乏厚度,甚至是有毒的。而且那个时候正好是中国当代艺术一个分水岭,艺术家的表达模式跟西方接轨,特别丰富,特别直接,有力度,有强度。这种强度,都会把你前进的步伐一下子加的很快。所有的人都要想点子怎么去表达自己的艺术观念。那个时候也有一些迷茫和疲倦的感觉,因为画了那么多年的画,却看到当时有大量画画的人,放弃绘画,从事观念艺术,或者装置行为、摄影……你就突然觉得就剩几个人干这个事了,突然有索然无味的感觉。所有的这些感觉,到今天对我个人来讲都有影响,都在影响我这种状态。这种虚无感一直会有,但同时会增加绘画的某种信念。我现在非常明确,任何好的或者不好的感觉,对我个人来讲都是非常重要的。甚至我对绘画的绝望,怀疑对绘画的能力的丧失……我跟朋友够会聊这个。绘画是什么?实际上所有的一切都可以表达,包括你对自己的那种困惑、怀疑,你的渴望,或者说所有的情感,所有的东西在绘画的当中都是极度重要的,都可以毫无保留地表达。

记者:是否和你生活的城市有关?南京的文艺情怀似乎一直有虚无和腐朽(无贬义)的传统?

毛焰:没有,跟南京没有直接关系,这可能是个人天性决定的。你有很多的愿望在逐渐实现的时候,你实现一份愿望,就会多出一份失落,甚至是一种绝望。虚无感随着那些东西的增加,会更加强烈。我永远会有一种感觉——始终处在表达过程中一种无可奈何。你要克制自己,压抑很多东西。你不压下去,它沉不下来的。从这个角度来讲,绘画的过程本身对于我来说特别重要,我的很多作品过去了多少年,我觉得都处在没完成的状态。因为你完成不了,那些不时浮现出来的现实的因素,你可能花几年画那么几张画,很难,很痛苦。南京给我的感觉就是比较安静的,比较适合我个人的状况,当初来南京是极其被动的,因为直接参与动乱的那几届学生都要往地方分配,北京不留人。其实我大概三年级时就定部留校,后来分到南京,也没打算调回美院去。包括很多地方学校要调我,但这种事我有一点惰性,有个性上的原因,我很难做到有求于别人,如果你要妥协很多东西,你要改变很多东西,我就不愿意动。我这几年才觉得好多了。其实上很长时间,南京对我来说都不太真实,真的,所有的人,很多朋友……我在南京生活了这么多年,就是比较习惯而已。

记者:但是客观上会让你边缘化,不是吗?

毛焰:若干年前很多人会用这个词——边缘化。我觉得这些东西都没关系,边缘化就是“变得不重要”,对不对?没关系,非常好。一个艺术家他需要的现实是非常有限的。我又是一个特别不喜欢跑动的人,我根本不喜欢那种大场面,北京那个场面太大了,至少我不是那种类型的艺术家,好多东西我不需要。十几年前我年轻的时候都不想去北京,我现在更没有理由去把自己重新放在一个新的生活环境中,或者说,地理位置发生改变,生活并不新。我不知道我适不适应,我平时很少想这种问题。

记者:我不太理解你刚才说的“表达上的无可奈何”?

毛焰:实际上包括这次展览的主题,名称就叫“意犹未尽”。我就觉得,绘画也好,人生也好,就是意犹未尽。“意犹未尽”的概念对我来说似乎就是,无论如何努力往死里表达,你没办法,你找不到,但是你又必须持续不断地做,实际上你根本达不到,就是这种概念。它与贪婪相悖,与野心背离,你认识到自己的有限,你作为一个个体,表面上所呈现出来的所谓你的个性,你的风格,你的形式,你的形象其实非常有限。

记者:你刚才说到你童年的现实环境是灰色的,为此你很幸运自己的父亲展现给你绘画这个的出口,但是在这个方向中,后来你的绘画又都定格在灰色中,它们之间有关系吗?

毛焰:灰色是回到我自己,这是我一直梦寐以求的一种东西,很小的时候,我就喜欢这种灰度,我不知道这个跟经历或者心态有没有关系。一直以来,我都不喜欢太单纯,就像天气一样,我就喜欢阴天,当然这也是我很有限的有别于他人的一种东西。有时候你要想跟别人有所区别很容易,很多东西你只要拿一点出来,去尝试一下,你就会跟别人不太一样。比如说灰色,这里面有很多小技巧,油画里面白颜色是不能随便用的,但是我的画里面所有的地方,最深的颜色里面也都有白颜色。我特别想追求那种所谓的绝对的灰,这种灰度的表达,在我看来就是最为细腻和微妙的,在语言表达上面我特别迷恋那种微妙的东西,也是能够让我达到一种很轻微的表达。这个过程中,很多年,我将近10来年没画过大画,就画很小的画,而且画的题材非常非常单一,就这么一种状况。我的一些想法确实经历了很长时间,现在才逐渐逐渐的显现出来。我跟我的朋友会这样解释这个事情的,我觉得有的简单的事情需要你花很长的时间去做,这个过程中,我可以获得我需要的东西。

- 毛焰:画出人生真味——艺术财经

毛焰:画出人生真味

文/喻若然

隐士再现江湖

说毛焰是绘画界的隐士应该没有人会否认。在各地艺术家们纷纷北上,在各种前卫艺术、新潮观念层出不穷的文化中心寻找一席之地的时候,毛焰却选择驻守南京,蜗居在象牙塔内,平静地画画、教书。当装置、观念、新媒体等艺术形式强烈地冲击着传统架上绘画艺术时,毛焰仍然执意探索他的肖像画创作,甚至将这一源自西方的艺术形式,画出了中国水墨山水意趣。最近,一向大隐隐于市的毛焰即将于9月在上海美术馆举办他的新个展——“意犹未尽”,推出近四五年来创作的60幅新作品,其中包括他标志性的“托马斯系列”以及几幅外国女性肖像。

对于一位普通的观者而言,这些新作实在算不得新。就题材来说,单单一个“托马斯”,毛焰就让我们从2000年一直看到2009年。其绘画语言也已趋于稳定,仍旧是灰色调、利用光影造型、明暗斑驳的笔触,在写实主义的框架下探索幽深微妙的人类精神世界。那么,这次展览的新作究竟与以往有何不同?毛焰说,这次的画作包含了几年以来积累的种种绘画以及绘画以外的认识,细腻与丰富的程度都比以前有增加,绘画语言的运用更加自然。这就是毛焰。看他的画总是需要沉淀下来,开启潜意识的大门,玩味每一个笔触,每一处细节。观者只有不断地沉潜与细读,才能品味出捕捉画家在具象形体中蕴含的抽象思考,冷酷压抑背后的暗潮汹涌——就在那些越来越细微、敏锐的笔触之间,传递着已步入不惑之年的画家对世界新的认识和体验。

师法传统,浑然天成

十几年前,毛焰曾放言,“我希望画面的每一个角落、每一个局部都充满表情。”对于一个24岁即在大型展览会上获奖的画家,其非凡的才情有着相当有力的佐证。那幅让他一跃跻身“千万俱乐部”的《记忆或者舞蹈的黑玫瑰》便是血气方刚的青年时期代表作。著名评论家栗宪庭也曾撰文称赞,“毛焰的作品放在欧洲任何博物馆的大师作品前,都毫不逊色。”那时的毛焰,是用才华在创作。然而,随着岁月变迁,他的绘画探索已经逐渐进入另一个阶段,现在的毛焰更多地是凭借阅历创作,有意收敛那些曾让他光芒四射的才气,笔触间少了几分充满艺术家气质的神经质与狂躁,而增添了几分理性和深刻。他坦言,如今的创作,在绘画背后支撑他的东西比以前更多,不局限于艺术家自己的小宇宙,而是“内心向世界敞开”。

这些变化的产生,一方面是画家有意向传统文化学习的结果,一方面也是被江南山水熏陶出的文人气质的自然流露。毛焰说,现在作画,时常是没有特别刻意的情绪,整个人处于“放空”状态,当感知到的事物穿越艺术家的身体,任情绪自然流淌,作品也将由此呈现出最浑然天成的形态。难怪,在近几年的毛焰作品中,似乎都不约而同地凸现出“空灵”的古典水墨山水意境。不论是托马斯还是新作中的外国女性系列,西方人像的清晰轮廓被画家刻意地模糊了,人像融入背景之中,难以捕捉的高灰度色调在冷暖虚实之间转换,将一切变得虚无缥缈,迷离不定。也许恰恰由于被画对象是外国人,这种传统文化的流露才如此清晰地被觉察到。

事实上,在多年的阅历积淀与中国传统文化的熏陶之下,毛焰身上的文人气质越发突出了。最明显的一点是:他从未用画笔直接表达对任何现实事件、流行观念的态度,而是执意由个体出发探究深邃的人性,如果说早年的《青年郭力——缅怀德拉克洛瓦》尚有年轻人特有的鲜明态度与情感,“托马斯系列”以后的作品却显得越发隐晦而暧昧。他说自己不喜欢太强烈、直接地表达情绪。同时,他对肖像画的执着探索也远未停止。他认为,肖像画作为表达精神的载体是没有边界的,是否一辈子画“托马斯”也不重要,最大的挑战在于:如何不断挑战创作者自身感受力、认识深度的边界。

毛焰是典型的“慢工出细活”,完成一件作品常常要耗费很长时间,有的甚至长达三四年。有时,他会一遍一遍地画一幅画,每一次都很轻微,每一次又都能产生新认识,在这个过程中逐步放弃一些过于刻意的东西,让作品渐渐趋于平静和自然。反复描摹同一件事物,“静则生灵”,让毛焰有了一种近似修行的体验。他对自我的“过度表达”适中保持高度警惕,显然有意克制自己天才的那部分,而将神经触角伸向更广阔的天地。

克制怀疑,理智生活

谈起绘画的市场价值,毛焰并不否认希望自己的画作获得好的市场反应,但他也清醒地认识到这种希望与实际创作之间的矛盾,因为自己并不是市场型的画家。有人认可自己的作品值得高兴,但超过了一定限度,就与艺术本身无关了,画家还是安静地创作为好。毕竟,市场不是由画家来掌控的。今年6月份,南京师范大学美术系有一位女生被查出身患白血病,急需30多万医药费。毛焰发动南京幕府山艺术家每人捐助一幅小画,他自己也捐出了一幅,总共36幅,最终被一位女收藏家以35万全部买下。也曾有人想出高价买走,但“那女孩就需要那么多钱”,因此他也没有同意。

在准备新展览的同时,毛焰已经计划好了他的下一步。在今后的画作中,他打算尝试更多地凸显物体的形象。他还将创作一组“女性”系列作品,为了保持整体风格的一致性,他会使用大尺寸的画幅来增强细节的表达,尽量使观者在视觉上有更加细腻深入的体验。

毛焰的好友、作家韩东评价毛焰是“疯狂的理智者”。生活中的他和作品中的他反差巨大。生活中的毛焰乐于享受工业文明带来的一切,时髦、随和,有时甚至不怕表现得浅薄;呈现在画作中的毛焰,却流露出虚无、疑虑甚至愤怒等各种情绪——即便是以极其克制和委婉的方式。这种有趣的对比和统一大约正是“毛式生存之道”的体现。想起《菜根谭》里那句名言:“醲肥辛甘非真味,真味只是淡;神奇卓异非至人,至人只是常。”清醒如毛焰者,应该早已参透这古老智慧个中三味。

- 毛焰:曾经的歌——艺术世界

毛焰:曾经的歌

王娅蕾 | 文

毛焰这几年蜗居在南京幕府山下一个新兴的艺术家聚集区,外面是货运仓库和汽配厂,里面的仓库则被艺术家们拿来做工作室和展示空间。毛焰的工作室靠近艺术区的最深处,内外墙壁洁白,没有油彩的痕迹。正如他现在的画面——浅浅的灰调子,人物漂浮在画框以内的另一个世界,清冷而虚幻。即使是三四米高的大型油画,也没有浓重的视觉冲击感和威慑力,显得宁静温和。这位生于湖南的油画家坐在工作室中间的旧沙发上,身材瘦小,面前的茶几上摆着功夫茶碗,一台立式摇头电扇在他身后一米送着强劲的风。曾经笔调张扬的天才少年,现在已经成为纯粹而内敛的成熟画家。眼前的面容和他画中曾经硬朗倔强的形象重叠,让人想到那些唱了再唱的歌,唱的是过去,歌者却已经走到现在。

“毛焰是一个非常有才气的年青艺术家……当中国人在经历了数不清的政治运动和生存价值的失落之后,作为毛焰感觉中的人因不堪重负而变得瘦骨嶙峋和神经兮兮。虽然我们已经走进新世纪,但是他的肖像作品怪异的角度,失神的神情,更加成为他内心灰色的意象和情绪的符号,表情作为一种可以表现人内心的视觉符号,仿佛即将消失、幻化、腐化……这是一个个表情正在消失的时代肖像。”栗宪庭在2001年这样写道,他2004年又为毛焰和何多苓写过《写实主义的探险》一文,将毛列为中国新写实主义的代表,而且是不同于刘小东、石冲的另一条线索。

毛焰曾经只为自己的朋友画肖像,直到20世纪90年代末,他开始以一位从卢森堡到中国留学的年轻人托马斯为模特,一画就是近十年。托马斯后来供职于卢森堡驻中国大使馆,而这个系列仍在继续。

Art World:您早期的《小山的肖像》、《我的诗人》等代表作品都用了很“热”的颜色,而现在则这么“冷”,几乎没有颜色的感觉在里面,这种转变是什么时间开始的?

毛:1995年有一个阶段,我突然开始画一系列的小画,一画就是十来年,几乎没再画过大尺幅的作品。我觉得有限的画面反而更适合我,能更加充分地去追求细腻和微妙的语言方式。画到现在这样的效果,是因为我自己需要安静的气质。我平时是很热闹的人,朋友很多,与之相对的就是需要静,有一种因果的关系在里面。而且你会发现,你现在所追求的,很可能是你多年前回避甚至反对的东西。绘画的演变绝对不仅仅是画家的兴趣所在,而是跟人自身的经验有关系。我没有刻意去追求这种转变,而是转变本身会告诉你,它有它的道理。这是自然之道。

Art World:所以现在的画,感觉上更趋于稳定。

毛:我觉得绘画之道就是让作品保持“最低的温度”。我很警惕自己在绘画过程中过度或者过快的表达,甚至有时候故意延缓时间和过程,包括增加施色的遍数,每一遍都很轻。这也是我现在自己很确定的方式。

Art World:一张作品会画多久?

毛:画得细的话要一年多,你看我工作室里这些画,有几张三四年都没完成,有一部分作品的周期比较长。这样也会造成同一个周期内我作品的面貌比较相似。没签名的都是没画完,签名才表示最终完成了。但是比较小的作品会要求自己一口气画完,因为颜料新鲜,笔触的感觉不一样。大型作品反而画得快,一个月不到,因为主要追求视觉的效果,有些细节点到为止就好。

Art World:您是手感至上的类型吗?

毛:不可能只是手感,就像不能说足球运动员有脚感,而一定说是“球感”。所谓的手感对我来说,就是“绘画性”,是我把所有的东西都降低到最低,但这个本质的东西依然存在。我早期的作品会表达得很充分,画面的每个角落都有丰富的表情。现在那些丰富的东西还在,但不再浮于表层,而是在里面。所谓手感、功夫、技巧等等,无非就是我画得更认真、时间更长而已。我的技巧很有限,从很早的时候起就有人谈论我的技巧有多厉害,其实没有那么夸张。

Art World:看您十几年前的画,感觉很张扬,现在几乎相反。您本人也经历这样的转变吗?

毛:这是很自然的,我毕竟已经过了年少轻狂的状态。我当时的作品中达到的很多程度,到现在也是难以企及的,但我不需要重复那个时候的东西,我现在更需要真实。里面有一种因果关系,与之前是相对的——相对尖锐、敏感和力度张扬,现在的自律和虚无就是一种因果。一个艺术家几十年走下来,很多追求的东西都是前后相悖的。

Art World:比如在2007年的保利春拍,您的旧作《记忆或舞蹈的黑玫瑰》拍到1001万,您也因此加入“千万俱乐部”。这件事对您有没有改变?

毛:没有太多改变。那完全是市场在疯狂,跟我没有关系。在市场里也看到了许多其他艺术家早期的精彩作品,但那些都已经是过去。自己的东西很可能自己都无法复制,也毫无必要。那次拍卖以后找上门来的人有很多,也有很多朋友也喜欢我十年前的作品,叫我再画。但是我自己强烈感觉到,曾经自己手上出来的东西再好都已经过去,而现在的东西也会过去,所以现在的东西更重要。因此我会对现在的作品有更高的要求——只有现在做得更好,才能对得起以前的好。不能依赖于过去,除非是现在可以延续的,否则再好的东西都不重要。当然身价这个东西有胜于无,但它决定不了你的命运,一步登不了天。

Art World:但是您这么多年来只画肖像画,这也是一种坚持?

毛:肖像画对我来说只是一种格式,当然也是我最为驾轻就熟的东西,画肖像只是一种基本功,所谓的“栩栩如生”其实是很低级的——我的目的不是要把这个人画得像。因为画得像对我来说很容易。如果没有我个人的情感、理解的话,表达得栩栩如生是低级而且没有意义的。所以我从来没有画过一张严格意义上的肖像画。不画肖像以外的主题不代表我不关注这个世界。人是一个载体,所有的东西穿你而过,会影响你的内心、精神世界。但并不见得我就要直接去表达这样一个命题。

Art World:您为什么如此着迷于肖像画?

毛:因为画肖像太简单了。很具体的东西就摆在眼前,能真实地描绘出来就很成功了。但就是这么简单的东西最符合我对绘画表达的理解,能达到一个悖论——我不画传统的肖像,剥离了肖像画“定制”的本质。我画了最久的这个系列《托马斯像》里面,托马斯对我来说只是一个幌子。我在很充分地表达他,但同时并没有去表达他的肖像,而是表达我自己的东西。营造这种悖论不是我的有意为之,但这个关系确实存在。我有时候也搞不清楚自己怎么迷恋这种方式,是不是有毛病(笑)。我记得1997年我和周春芽在北京的联展,题目就叫《肖像性质》,那个展览里有《我的诗人》,还有李小山的肖像。当时我强调的是个人的精神特质,是某种脆弱的或者犀利的感觉。但在这么多年的实践中,有些想法会越来越清楚、越来越丰厚,而有些则消解或者遗失掉了。

Art World:这种重复,或许像一种修行?

毛:说修行还不至于,但感觉上有点类似吧。就像塞尚会反反复复地去画一组静物——我非常喜欢看大师的作品,有些作品中没有确切地表达某种东西,但是会轻微地弥漫着一种气氛。因为所有的作品都饱含着情感的过程,我的理解是绘画是活的,不是死的。绘画表面的虚无、平静下面饱含感情。比如蒙克的绘画非常简单,但是简单甚至粗糙的几笔,都能感觉到富有激情,颜色和线条之间有一种热忱和坦率。这种东西特别让人感动。

这些大师是我精神上的一种寄托,因此在很多方面我会特意去遵循一种规则,或者说一种古典的情结。这些情结的存在让我对绘画始终抱有敬畏之心,不会觉得它只是表达自我的一种工具。这也与我的个人经历有关。我从很小的时候开始学画,就把这些大师当成心中的神。这种敬畏的心态一直存在,让我从来不敢瞎画。有些人在绘画里面很随便,想表达什么就表达什么,但是我不会。

Art World:这种态度与您的生活状态有关吗?

毛:我一直有读书的习惯。我父亲是业余美术工作者,藏了很多书,都拿牛皮纸包上书皮,钢笔写上书名。因此我从小就囫囵吞枣都看过很多世界名著,比如《飘》、《珍妮姑娘》、《福尔摩斯探案集》等等。现在我身边搞写作的朋友很多,他们的圈子更加纯粹、更加简单。比如韩东,我非常敬佩他,他也给了我很多动力。这些朋友会给我推荐不错的书,让我看了很多好书。

现在我还在南京艺术学院当老师,从1991年到现在已经18年了,没有什么改变。不评职称不升级,当当助教就行了。我个人没有这个概念,很习惯这样。十几年来我教了很多学生,其中有些很有灵气,只是大家还都不知道。毕业以后一直坚持画画的学生我都很喜欢,会一起喝酒、看画。

Art World:您和很多画家合作过双个展,这在圈子里好像蛮少见的。

毛:这其实满偶然的。比如我和何多苓老师办双个展是因为我们是最好的朋友,虽然年龄相差二十岁,属于忘年交。我从很小的时候起就非常喜欢他的作品。最早的双个展是与周春芽合办的,然后是刘野、夏小万等等,都是我喜欢的画家。我觉得一个人办一个展览太正儿八经了。两个人合办就比较轻松、过瘾,风格迥异、志趣相投。而且双个展的客观呈现会有一些相对应的东西,来看画的观众也会觉得比看个人的有意思。明年我还会和何老师在成都办一次双个展。人本来就没办法只活在自己的世界中。

Art World:您画里的主角“托马斯”现在在做什么?

毛:他目前在上海,负责他们国家的世博会国家馆。每过一段时间我会约他拍一些资料素材。现在画的这些都是新鲜准备的照片。

Art World:托马斯对您持续了这么多年来画他有什么感觉?

毛:他估计也没想到,已经晕了吧(笑)。

Art World:这个系列可能持续到什么时间?

毛:可能会持续,当然我也会增加一些新的形象。

- 毛焰:比纯粹再透明一点——新民周刊

毛焰:比纯粹再透明一点

从浪迹江湖的“朋友”,到“托马斯”,以及“情色的女人”,毛焰在越来越虚幻的作品中,提升了中国油画的品质和另类的写实意味。那种强烈的不确定性,不仅是画家本人的写照,更是当下中国人集体的面容。

本周二,上海美术馆以格外亮丽的姿态迎来了南京画家毛焰的个展《意犹未尽》,说它亮丽,是因为展览的总体布置出于一个法国环境艺术家和她团队之手,布展前他们特意带了色卡赶到南京毛焰的画室看了他的近50幅展品,那是一种相当内敛的灰绿或灰黄的调子,然后他们设想了很多方案来适应它们。在画展开幕式现场,记者看到这个团队的所有成员表情轻松。

在参加开幕式的来宾和观众中,毛焰混在人群中是比较难找的,因为他个头不大,服饰也不是很出挑,主要是他不习惯在这种场合显山露水,他甚至有点害羞地逃避上海同行的目光。

但是,他的画太强烈了,那是一种低调的、似乎是微风吹皱春池的强烈。有人说,在他的画前呆久了,经常会感到一阵晕眩袭来,还有人说,会感到有一道白光闪过,浑身就像触电一样。

体魄壮实高大的托马斯微笑着走向《托马斯系列》,领受大家友善的目光。没错,就是这个托马斯,毛焰的长期模特儿——其实是相当默契的合作伙伴。他本人比画中的形象帅多啦,周正、温柔、富有教养,有一种欧洲人的古典气质。当然,请注意他的鼻尖,略微上翘、削尖、有明显的侧影,于是就带了一点点小顽皮。

托马斯很值得画吗?或者,毛焰为什么选择这个欧洲人?

这是一种很有趣的关系。从个话题切入窥视,也许是所有观众的愿望。

天才进京的第一件事

许多画家拿起画笔是出于一次偶然,但毛焰是为画画而生的。毛焰出生于湖南湘潭,他的父亲毛大亮在长沙一个科研所里工作,是一个“业余美术工作者”——这是毛焰自己的话,此外他编过舞蹈、摆弄过乐器,还写过小说,毛焰三四岁时,就跟着父亲在单位里,看他画画,办展览,受到最初的美术熏陶,对涂涂抹抹也发生了强烈的兴趣。但毛大亮在那个时候没法实现自己的理想,于是将心中的愿望移植到儿子身上,希望延续一种闪亮的生命。

毛大亮开始教毛焰如何运笔,如何捕捉前眼的色彩与光线,油画、水彩、水粉、素描……像五谷杂粮一样塞给他吃。毛大亮的朋友和学生也一直看好这个瘦小的孩子,在他这个年龄层上,小家伙一直是拔尖的。大家就像一群母鸡,围着等待这枚蛋啄破壳,钻出毛绒绒的身体。而毛焰学得很轻松,似乎这一切都跟吃饭、睡觉一样,是出于一种本能。毛焰长大了,野心勃勃,意气奋发。他遇到了一个好时代,挤上火车去北京报考中央美术学院。但是他显然没有做好准备,文化科目考得一塌糊涂。名落孙山的毛焰灰头土脸地回到家乡,想去一所中学当美术老师。他父亲得知儿子这个想法后非常伤心地说:“中学老师有许多人可以胜任,我对你的期待可不是这个位置啊,你怎么可以轻易放弃呢?”

毛大亮押宝押对了,第二年,毛焰经过卧薪尝胆式的努力,终于考上了中央美院。“报到后,结伙上街去撮了一顿? ”记者问。

“当时我们油画班第二画室只有四个学生,我们结伴而行,直扑军博,去朝拜一张画,它就是陈逸飞与魏景山合作的《占领总统府》。”

倒行逆施的古典情怀

南京北部靠近长江大桥的一个艺术园区内毛焰的画室设在这里,这个以前生产面包车的厂区里还有30多个工作室,一辆刚买不久的“路虎”停在门口,看上去至少有几个月没洗了,园区里的小孩子在后车窗的灰尘上写了几行歪歪斜斜的字。

毛焰的画室是前年租下的,360平方米,他还嫌不够,又破墙搭了一个天棚,阳光从头顶的大幅玻璃窗流泻下来,罩着下面的油画架,摄影师看了一眼镜头就惊呼:光线太棒了!

黑檀原木做的一张中式画桌上排列着三个笔筒,这是毛焰挥洒水墨画的地方,但同样布满了灰尘。一只到处开裂的皮沙发是专供来访朋友坐的,他自己喜欢坐一张条纹布面沙发,两者共同之处是一样的破旧肮脏。一只可能是从某个剧团里捡来的戏箱权作了茶几,堆满了未洗的茶盅和油画颜料。靠墙搁着好几幅作品,是为展览准备的。架上还搁了一幅,画到一半,毛焰表示肯定在最后一刻画完,一起打包送到上海去。

这是上个周末,记者去南京采访毛焰时看到的情景。以往毛焰参加一些联展时,经常将未完成的作品送去,待画展结束后再继续画,许多观众包括同行居然看不出是不是已经完成了。他拿回来后,慢慢点起一支烟,面对未完成的作品,其中那些不为人知、难以察觉的精微部分,就在画室里慢慢享用。他像一个技艺高超的钟表匠,专心致志地校正一只老旧的劳力士。

如果你对80年代中后期中央美院油画系的教学情况有所了解的话,特别是对那拨学生的能力与狂妄有所了解的话,那么本记者就没有必要对毛焰在那里的求学过程啰唆几句了,说难听点,谁教谁还不知道呢。一句话,毛焰在北京他已经有点名气了。再说啦,男孩子嘛,学艺术的,玩玩电脑游戏、泡泡酒吧、睡睡懒觉、侃侃大山,把个别同志贬损一通,很正常,毛焰就是这样打发光阴的,很快乐也很放松。然后毕业了,举起一升装的啤酒杯,向老师同学、还有首都告别。

1990年。

事实上,经过八五新潮洗礼的北京,在西方各种新思潮与中国传统文化猛烈碰撞下的北京,毛焰是没法像宰予那样安然昼寝的。他的导师中,影响最大的是赵友萍,她是留苏的,还有几位导师也非常关心毛焰的成长。第二画室对学生的要求就是熟练地掌握和运用现实主义的油画语言。这样集中一个时期的刻苦训练造就了毛焰作品中特殊的艺术品位,也使得他在心态上总能超越所谓“当代艺术的实践”的时尚潮流。说起来容易,做起来就需要很大的定力。当时中国艺术正处于一个大的转型期,艺术家和批评家们都力图与国际接轨,进入西方当代艺术的大框架中,对毛焰这样具有古典情结的人来说应该是极大的磨难和考验。

“当时是各方面都最好的时期,各种流派、各种风格在学校里交流、交融,师生之间几乎没有任何隔阂,心都是敞开的。我的同学中走出了刘小东、方力钧、赵半狄等今天风头仍然很健的艺术家,来美院进修的外地艺术家也很多,他们带来了新鲜空气。”毛焰一脸真诚地说,“各种艺术思潮我都要了解,我还看了许多诗歌、小说、话剧、电影等,新的东西我都如饥似渴地接受。那时,美院里所有的地方,所有的人都在讲空间,讲激烈,讲力量,讲震撼,我和这些没有关系,我有自己要做的事情。有一条我是抱定宗旨不变的,那就是画画一定要地道。这对我而言一点也不能含糊,要学,就必须扎扎实实。”

毛焰和他的朋友们

离开北京这个当代艺术中心后,毛焰来到南京艺术学院任教,无论在教学还在创作中,他都以湘伢子的性格,固执地探索古典绘画语言向当代艺术的转型。为了强调这一点,他扔下了写生,而且主要画肖像。肖像画是一个古老的题材,几乎是油画一出现,肖像画就随之诞生,并很快成熟。但在中国绘画的传统观念中,它的地位并不高。油画进入中国后,一开始是承担了宗教传播的使命,由画匠们实施最早的操作。后来,中国画家、包括吃过洋面包的那一批人,也没有很好地掌握技巧,即使是老一辈画家也不行,表现力太差。在采访中,毛焰希望记者不要太具体地表达他的看法,但同时又认为,一直到了陈逸飞、陈丹青,中国的肖像画才算成熟了。

到了毛焰出来混的时候,中国油画中的肖像画又将如何呈现呢?摄影术的普及,电子传媒的覆盖,都大大削弱了肖像画的权威性。油画无法与摄影照片比真实度,长期来受现实主义概念灌输,习惯用“像与不像”的标准来评判一幅肖像画的中国观众,又似乎有着很强大的审判权。这就是毛焰面临的文化背景。

好在毛焰有一帮欣赏他、理解他的朋友,他在美术圈之外的文学圈、摄影圈都有朋友,他就画他们,丑陋一点、变形厉害一点也不妨。最早的“朋友系列”就是这样产生的。

美术评论家皮力说过:“毛焰所试图捕捉的不是物理学意义上的‘像’,而是一种心理学层面的‘像’。我们将他的绘画理解为当代人的精神肖像是一点也不过分的。”

这可以作为解读毛焰作品的一把钥匙。

1992年毛焰画的美术评论家李小山,如果说还是相当具象的,带有法国古典主义绘画的印痕,有点向前辈致敬的意味,到了1996年的《我的诗人》、《X·S肖像》等,就出现了明显的变化。这些人物大都站立着,既不喧哗,也不急躁,所有的叙事性背景被一扫而光,这些肖像中人物不是以某个生活片断出现在我们眼前,也不是符号性地呈现在时代的光斑中,欲表达画家的某种思想或宣言,而是为绘画本身而站立在这个时间节点上。毛焰似乎有意消解了人物的丰富性和复杂性,使人物吸引我们的理由变得简单无比,就是一个戏剧性的场景,一种绘画语言,让我们感动或深思。从哲学上说,也可以这样认为:中国的“他们”,正在等待中国的戈多。

但仅仅是画自己熟悉的朋友,一方面他感到有本民族的东西隐藏在里面,另一方面,形式主义的欲望又让他不尽满足。

上帝派托马斯来见这个画家

毛焰决定重返人的内心世界。这个时候,他的“朋友系列”在画布上有了更多的表情,他们的衣着也趋于怪诞,可能是整齐的凌乱,也可能是色彩的不确定,人物的眼睛里闪烁着不安的神色,还有嘴角和扭曲的躯干,都在犹豫、紧张、恐惧、焦虑……现代人所有的心理变化,在画布上都会呈现。或者说,都是毛焰自己的内心呈现。

毛焰希望将对象画成一个有深度的人,一个被丰富的内在性所覆盖的人,一个被灵魂折磨的人。这个时候,几乎重要城市里的当代艺术展,策展人都会叫上他。也许是因为他的画有个性,另类,现代人的困惑,很容易引起共鸣和喝彩。但接着问题来了,毛焰发现陷入了一个自我设置的圈套之中,他对记者回忆时说:“很多东西是在绘画过程中显露出来的。如果硬要说,我也可以找到一些东西来自圆其说,比如从形象的角度,从观念的角度。我画这个系列肯定有我的道理。其实我一直不喜欢也不愿意画那种中国特色的东西,中国符号乃至中国形象,我已经有拒绝的资本和理由。托马斯不知不觉地符合了我的这种倾向和选择。”

是的,这个时候托马斯来了。

托马斯是一个卢森堡人。90年代中后期在南京学汉语。他是毛焰一个英国朋友的朋友。在一个朋友的聚会上,毛焰看到了他,他向毛焰走来,面带真诚的微笑。这一瞬间,毛焰感到他是上帝派来的天使,专门是为他捏塑出来的模特儿。虽然他那么壮实,体量那么庞大,但托马斯给他感觉就是典型的欧洲乖孩子。当时托马斯也就二十四五岁,单纯而且有涵养。后来毛焰去伦敦做展览,托马斯特地从卢森堡赶到英国,陪了他两天。

毛焰认定托马斯是一个可以入画的形象,而托马斯也完全理解毛焰的艺术行为。他们的合作是愉快的,没有所谓肖像权方面的麻烦。毛焰给托马斯拍照,让托马斯摆各种姿势,而且是那种并不舒服的姿势,他非常顺从地做了。毛焰画好后给托马斯看他自己的形象,那已经不是他了,而是另一个叫托马斯的外国人。他很认真地笑着,认同了。毛焰说:“他们(指外国友人)会很自然地去理解、去接受一些东西。他们抱有平常心,按照自己的生活体验看待艺术这件事。我觉得这恰恰是对艺术的尊重,而不是由于一些额外的东西在起作用。”

几年后,托马斯进入卢森堡驻华大使馆工作,有一天他打电话给毛焰,说:“我现在经济上没有问题了,想收藏一幅你画的托马斯。”毛焰当时就乐了:“我会送你一张的。”

托马斯让毛焰画自己是不收钱的,毛焰则会隔一段时间送他一张。这是君子协议。

他们的友情发展得很顺利,也很单纯。有一次在成都,毛焰和托马斯住在成都画家何多苓的家里,客房里只有一张床。酒吧里聊到很晚了,托马斯要先回去睡觉,毛焰就他开玩笑说:“你不要担心,尽管睡,只要睡的时候把两条腿叉开。你叉开的地方就足够我睡的了。”大家当场笑得前俯后仰。后来毛焰回去了,两人挤在一张小床上。睡到早上,毛焰发现床的中间还空出一大块。原来他们都是侧着睡的。

现在托马斯在上海世博会负责卢森堡馆的设计与建造。

一条河如何穿越沙漠

毛焰从托马斯身上找出了突破口,一个艺术理想的载体。托马斯帮助他解决了一个问题,那就是身份的消解。

如果说以前毛焰的肖像画关注人的灵魂,到了托马斯系列中,他开始以另一种方法来讨论了。画面上的人物,与其说是人物,不如说是人的轮廓,人的影子。画面上的人同深灰色的背景色融化在一起,犹如一个在雾天行走的人,融入了浓雾之中。人的器官和表情,以及很难在现实中扭曲到位的形体,从画面中脱颖而出,而另外一些东西,比如脸庞、额头、脖子等,通常被画面吞没了,使这些器官变成另一个广阔的世界,产生了无限的可能性。

不断放弃,不断减弱,不断虚化……同时又在不断突围,不断深刻,不断强烈。这就是毛焰。

如果再从哲学层面上来讨论,那么不妨设问:一个人的面孔,真的是与他自己相同的一张脸吗?一个人的面孔,在多大程度上代表他自己,或者人类整体?一个器官可以包含多大的世界?隐藏多少秘密?从这个意义上说,每个人的面孔,都是他者的世界。

有一次,毛焰在接受南京作家韩东的一次访谈时,跟韩东转述了一个奥修讲过故事:一条河流流经沙漠,想要穿越过去,这怎么可能呢?穿越沙漠你就不存在了,就完蛋了。后来风告诉它要学会信任,然后把它带到了空中,变成了云。到达沙漠的另一端,再变成雨,降落下来。

显然,毛焰将自己比喻为这条渡过沙漠的河。

情色裸女以及《托马斯·毛》

最后,对本文作几点补充。

托马斯系列还将继续下去,这是肯定的。托马斯本人也非常乐意。

朋友系列也会继续下去,但可能是另一种面目。他的朋友也求之不得,排队等。

对女人重新点燃激情。毛焰要画的女人是洋妞,很壮实很肉感的那种欧洲女人,淡粉红的裸体。甚至他已经想好了,高度在三四米的大尺幅,让她们赤身裸体穿上名贵的貂皮大衣,衣襟敞开,摆出各种放荡的姿势。放纵的色情,直勾勾的挑逗。在之前,毛焰画过《巴黎,巴黎》、《戴帽的Lisa》、《Kim》等以女性为主题的作品。毛焰说:“她们妖冶、艳丽、骚动,给古典主义注入新的生命力,并以此来照见当下。面对她们,会有许多人想到自己的污秽。”我们有理由认为这是毛焰相对新的极点运动的开始。

前不久,毛焰与画家朋友们帮助了一个女学生,那是南师大的一位研究生,得了白血病,毛焰和朋友每人捐出一幅画,卖了30万,悉数送到医院。毛焰与女学生素昧平生,“但这是义不容辞的”,他说。

这次画展,如果读者有兴趣看看的话,一定不要错过一部在展厅反复播放的电影。片名《托马斯·毛》,编导是南京作家朱文。朱文是毛焰的老朋友,有一次向他透露想拍一部片子,人物以毛焰与托马斯为主,有故事,有人物,还有武打戏穿插其中,是魔幻风格的那路戏。毛焰正好卖画得了200万,就全部投了进去。一干人马在内蒙的坝上外景地拍了一个月,毛焰和托马斯大大过了一把瘾。毛焰演的角色是一个农民,打猎的场面让他兴奋不已。

“贾樟柯早几年就请我演一个角色,他说这个角色非我莫属,后来得知要拍两个月,我不干。”毛焰很得意地还向记者透露:他看过法国作家普鲁斯特的《追忆似水年华》。

“据我所知,在中国的作家圈内,确实有许多人买了这套五卷本的巨著,但百分之九十九的人没有读完,甚至一本也没读完。这跟《尤里西斯》在中国的遭遇相似。”记者不相信。

“是的,我真的读完了。我还特别欣赏《在斯万家那边》这一卷。”

不厌其烦地、津津有味地描述琐碎的细节,充满激情和才气,普鲁斯特是这样,毛焰也是这样。但是,这需要极敏感的观察力和排除外界及内心干扰的持久耐力。不过记者不明白,你为什么不把价值190万的“路虎”洗一洗呢?

——新民周刊